Sometimes it is a journey to find a good bottle of wine

One of my favorite links that I check almost daily is the news article aggregate of Wine Business Monthly. It’s a nice one page purview of what’s going on in the wine world. On one visit to the site, my eyes fell upon the click-bait title 10 Words To Look Out For On Affordable Wine Bottles. I clicked on the article and clicked and clicked and clicked some more (The Drink Business loves the slideshow format) and now my head hurts.

To save you the clicking, here are the 10 magical words (or, more accurately, phrases) that Business Insider and Jörn Kleinhans, owner of the The Sommelier Company, promises are virtually silver bullets that will help you bag high quality wine at affordable prices.

1.) ‘Classico’ on a Chianti

2.) ‘Riserva’ on Italian wines like Barolo or Chianti

3.) ‘Gran Reserva’ on a Rioja

4.) ‘Old Vine’ on a Spanish Grenache or California Zinfandel

5.) ‘Cru Bourgeois’ on a Bordeaux

6.) ‘Meritage’ on a California Cabernet Sauvignon

7.) ‘Trocken’ on a Riesling

8.) ‘Premier Cru’ on Burgundy

9.) ‘Cru’ on a Beaujolais

10.) ‘Grand Vin’ on a Bordeaux (Bordeaux Geeks who really want a belly laugh should just jump to this slide right now)

The issue is not that these are “silly words” or that there is not any benefit in learning what certain key phrases mean on wine labels. Quite the opposite. These are actually extremely helpful words and phrases that would be in Chapter One of any wine book titled How to Know Just Enough to Be Dangerous. However, it is beyond ludicrous to present these words as the secret code crackers that help you “navigate your way to an exceptional bottle of wine.”

A full-bodied yet “light” wine between 12-14% made from who knows what.

I understand how alluring the thought is of magical words that only the wily and the wise know which, when whispered to you, opens up the gate to all the gems hidden in plain sight on wine shelves and wine lists. But there are no “magical words” in the world of wine and peddling a list like this as click bait to readers is like selling

magic beans to Jack.

“Well, Jack, and where are you off to?” said the man.

“I’m going to market to sell our cow there.”

“Oh, you look the proper sort of chap to sell cows,” said the man. “I wonder if you know how many beans make five.”

“Two in each hand and one in your mouth,” says Jack, as sharp as a needle.

“Right you are,” says the man, “and here they are, the very beans themselves,” he went on, pulling out of his pocket a number of strange-looking beans. “As you are so sharp,” says he, “I don’t mind doing a swap with you — your cow for these beans.”

“Go along,” says Jack. “Wouldn’t you like it?”

“Ah! You don’t know what these beans are,” said the man. “If you plant them overnight, by morning they grow right up to the sky.”

“Really?” said Jack. “You don’t say so.”

“Yes, that is so. And if it doesn’t turn out to be true you can have your cow back.”

Now those who remember their childhood tales will know that those beans were, indeed, magical and the old man wasn’t necessarily lying. Planting the beans did produce a stalk that grew straight up to the sky. He just forgot to tell Jack about a few giant details that ended up causing, you could say, a few problems for the lad.

The same is true with this list. Jörn Kleinhans, the wine expert behind the list, isn’t necessarily lying in that knowing these phrases will be helpful in selecting good bottles of wine but he’s overselling it in his simplicity (i.e. “Wine that is only labeled Chianti is usually not very good. If you see ‘Chianti Classico,’ that is always a good wine.”) and leaving out some giant details that could end up leading you to A LOT of not-so-enjoyable bottles of wine.

Moral of the Story (TL;DR version)

Don’t be fooled by the promise and simplicity of magic beans. There’s ALWAYS more to the story. If you’re happy with that, you can stop reading now and start surfing Netflix for Jim Henson’s adaptation of Jack and the Beanstalk: The Real Story. But if you want to plant these magic beans, we can take a deeper look at this list and mine out the key details that will give you a better chance of finding the right wine for you the next time you’re at a wine shop or looking at a restaurant’s wine list.

1.)‘Classico’ on a Chianti

The assumption: “Wine that is only labeled Chianti is usually not very good. If you see ‘Chianti Classico,’ that is always a good wine.”

Some of these may be good, some not so good but they are all from the same Chianti Classico region.

Chianti Classico

is just a region like Napa Valley. Just as there are “good” Napa Valley wines, there are also “bad” Napa Valley wines. The same is true with Chianti Classico. Looking for a region alone on the label is never a winning strategy. Now, yes, there are some slightly more restrictive laws regarding yields, aging and blending (such as the fact that

white wine grapes are no longer permitted in Chianti Classico). And, yes, you can make a fair argument that the

terroir of the “Classico” zone of Chianti is better than the larger Chianti area–just like you could make a fair argument that the

terroir of the Rutherford AVA is better than the larger Napa Valley AVA.

BUT… good producers make good wines in a variety of terroirs and many of those more restrictive laws of Chianti Classico, such as lower yields and not using white grapes in the blend, are followed by quality minded producers in the greater Chianti area anyways. In fact, from many producers you’ll see offerings of both a Chianti and a Chianti Classico. The difference will often not be in the quality of the grapes and winemaking but rather in the use of oak and aging with the Chianti bottling often being more fresh and fruit driven, meant to be consumed younger and usually with food. That’s not a bad thing if that is what you want.

What you should do instead: Ask about the producer. Again, good producers make good wine and they rest their reputation on every bottle that is labeled with their name–whether it be on a Chianti or a Chianti Classico. If you are just looking for a fresh and easy drinking Chianti to go with a dinner, you don’t necessarily need to spring a couple extra dollars more for the Classico if a good producer’s Chianti is available.

2.) ‘Riserva’ on Italian wines like Barolo or Chianti

The assumption: “This term indicates the winery has full confidence this wine has high potential and shows their best quality. Since the term is regulated in Italy, a riserva is always better than a non-riserva and is an important word to look for in Italian wines.”

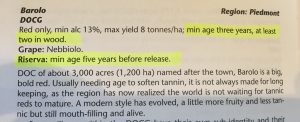

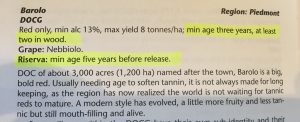

Err….no: I’m going to do a shout out here for one of my favorite wine books, Peter Saunder’s Wine Label Language . Published in 2004, it does need to be updated in a few places but for the most part it does an awesome job of telling you exactly what the regulations are for different wines. In the picture below we see what distinguishes a Barolo Riserva from a regular Barolo.

. Published in 2004, it does need to be updated in a few places but for the most part it does an awesome job of telling you exactly what the regulations are for different wines. In the picture below we see what distinguishes a Barolo Riserva from a regular Barolo.

The difference is age before release. Yes, you can follow the logic that a winery will save their best plots and best barrels for the wines that they proudly will label as a “Riserva”. But that certainly doesn’t mean that if you are standing in front of two bottles, say a 2011 Barolo and a 2010 Barolo Riserva, that the 2010 Riserva will be the better bottle, right now. In fact, often its not. Often the reason why Riservas get more age is because they need it and may need even more aging beyond the release.

What you should do instead: Ask which wine is drinking better now. When making a wine purchasing decision, your focus should never be on getting the categorically “best bottle” (by whatever vague or subjective standard) but rather on getting the best bottle for you at that moment. That 2011 Barolo which was from a very good year may be at a point in its life where it will give you more pleasure drinking it now than the 2010 Riserva even though 2010 was an outstanding year. And remember, producer matters too. A good producer’s non-Riserva can easily beat a sub-par producer’s Riserva even in classic vintages.

A gimmicky frosted bottle also isn’t a sign of quality either.

“… you’re always looking for, without exception, the Gran Reserva,” says Kleinhans. “It means this wine has a strong oak flavour, the hallmark flavour of Rioja. It also guarantees this wine has been aged in oak for two years or more, and an additional three years in the bottle.”

Err….no: OMG NO! I’ll save for another blog post about the changing style of Rioja but most wine folks nowadays would say that the Reserva level (minimum 1 year in oak, 2 year in bottle before release) is more indicative of a winery’s “style” and consumers are flocking towards the fresher and more fruit forward styles of a lot of Crianzas (minimum 1 year in oak, 1 year in bottle) and Jovens (only a few months, if any, in oak).

What you should do instead: Pick the style that you enjoy. If you like oak, more dried fruit, spice and earthier flavors, then by all means, grab a Gran Reserva Rioja. There are definitely some great examples out there. But if that is not the style you like, then someone telling you that “without exception” you’re not getting the right bottle if it is not a Gran Reserva is dead wrong. The wines of Rioja are not monochromatic and I dearly pray that anyone who has so been lead astray with such horrible advice will give Rioja another chance and seek out some of the exceptionally well made Crianzas and Reservas out there.

4.) ‘Old Vine’ on a Spanish Grenache or California Zinfandel

The assumption: “The older a vine is, the smaller the grapes are and the more concentrated and jammy the flavour will be.”

Err….no: Well….kinda. Older vines have better means of naturally regulating the yield (smaller yield, not necessarily smaller grapes) and there is some relationship between yield and wine quality–though it isn’t so cut and dry.

One of my personal favorite Old Vine Zins is St. Amant Marian’s Vineyard from Lodi. Assistant Winemaker Joel Ohmart (pictured with me) says that these vines, planted in 1901, still produce around 3.5 tons/acre of outstandingly spicy fruit.

The problem is that the term “Old Vine” isn’t regulated anywhere. It could be applied to a 20 year old vines just as easily as 100+ year old vines. It could also be used to refer to a wine that may have been 60% sourced from 40+ year old vines with the rest supplied by 10-20 year old vines. It’s truly up to the producer (or marketing department) to decide what the term means.

What you should do instead: Ask about the producer. Find out the story about the wine and look for a vineyard name. Truly “Old Vine” wines will have a story behind them and a vineyard whose name the producers are usually quite proud to put on the label. Plus, in the US, vineyard designated wines DO have regulations that they need to follow in order to use the vineyard’s name on the bottle which includes having 95% of the wine sourced from just that vineyard.

5.) ‘Cru Bourgeois’ on a Bordeaux

You may or may not see the word “Cru Bourgeois” appear on a label because, again, the system is a mess. Your best bet is to talk to a knowledgeable wine professional and ask for a recommendation.

“Those are the chateaus not allowed into the Grand Cru classification 150 years ago. Several outstanding chateaus were left aside, and nowadays these wines not labeled Grand Cru, but Cru Bourgeois, you can get at a great value. It’s the level right under the Grand Cru level people are paying thousands for.”

Err….no: Simply put, the Cru Bourgeois system is a mess. This will certainly be a fodder for another blog post in the future but the key thing that you should know right now is that the term “Cru Bourgeois” has been so diluted and devalued that many of the best estates in Bordeaux that could use the term, such as Chateau Lanessan, Ch. Chasse-Spleen and Ch. Sociando-Mallet, etc. have declined to do so.

What you should do instead: Ask about the producer. Are you noticing a theme? While there are certainly lots of outstanding values in Bordeaux beyond the fabled 1855 Classification, there is no magic silver bullet term that is going to make those values jump out at you. You can either figure it out by trial and error (which following this Cru Bourgeois magic bean would lead to a lot of the latter) or you can ask people who have already done the trial and error themselves.

6.) ‘Meritage’ on a California Cabernet Sauvignon

The assumption:“Relatively simple, but Meritage is a marriage of words between “merit” and “heritage,” and you’ll only ever find it on Bordeaux-style wines from California.”

Err….no: So. Much. Wrong. First I would encourage you to check out the Meritage Alliance page where you’ll find out that, No, California is not the only place that you’ll find “Meritage” wines from. Oh yes, there are Meritages being produced across the United States in places like Washington State, Virginia, Missouri and even Rhode Island. Also, a Meritage doesn’t even need to have any Cabernet Sauvignon in it. You can make a “Right Bank Bordeaux-style” Meritage of Merlot and Cabernet Franc or you could make a Carménère-Malbec blend (which sounds really cool) and call it a Meritage.

You can even get a Meritage made in Canada, such as this one from Burrowing Owl in the Okanagan region of British Columbia

However, the main reason why this magic bean is bad advice is that the term Meritage is appearing less and less often on wine labels. That’s not because wineries are not making Bordeaux-style wines anymore but rather because fewer wineries are seeing the need to pay a group like the Meritage Alliance membership dues and trademark fees to use the term ‘Meritage’ when they can just come up with a proprietary name and sell it as a red blend.

What you should do instead: Walk into the Red Blend aisle or flip to that page in the wine list and, you guessed it, ask about the producer.

7.) ‘Trocken’ on a Riesling

The assumption: “In the US we often enjoy drier wines, and the Germans have a word for it: trocken,” Kleinhans says.

Err….no: Actually, the common knowledge in the wine industry is that Americans “talk dry but drink sweet” (another future blog post topic). This is why wines like Apothic Red and Menage a Trois are so popular. Even with noticeable sweetness, they are marketed as just “red wines” which most people assume are always “dry”. It’s also how Meiomi Pinot noir, with Riesling and Gewurztraminer blended in, became a $315 million dollar success. It was a subtly “sweet-ish” Pinot noir that Americans could happily guzzle down without even knowing that there was any residual sugar in the wine.

What you should do instead: Enjoy what you like! (Another reoccurring theme here) If you like sweet wines, wonderful! If you like Apothic, Menage a Trois and Meiomi, that’s fantastic. If you don’t, that’s fine too. There’s plenty out there for everyone. You don’t have to seek out a dry, trocken Riesling just because someone is telling you that is the better wine. Besides, one of the reasons why Riesling is the darling of sommeliers is that the interplay of the wine’s natural sweetness with its lively acidity is magical with food pairing. So knock yourself out.

8.) ‘Premier Cru’ on Burgundy

The assumption: ““With some luck you will find one under $25 and know with confidence you have a single vineyard, highly classified Burgundy rather than a lesser level,” Kleinhans says.”

Err….no: This magic bean isn’t horrible advice. But, again, it’s incomplete. For one, you can have a blend of multiple Premier Cru (or 1er cru) vineyards and still have it labeled as Premier Cru. Second, it is actually getting harder and harder to find good Premier Cru Burgundies under $25.

What you should do instead: The better bet for value is to look more for “Village-level” bottles from areas like Mercurey or even regional Bourgogne levels from outstanding producers. As the mantra goes, good producers make good wine. This will always be your safest bet.

9.) ‘Cru’ on a Beaujolais

The assumption:“These other so-called Cru Beaujolais, you know under $25 that you found a Beaujolais that is as serious and as good as many of the great red Burgundies.”

Err….no: I love Cru Beaujolais but I would never compare these to the “great red Burgundies”. That’s not the point of them as they are made from two different grapes. The Gamay grape used in Beaujolais lends itself better to fresh, floral and slightly spicy wine styles that can pair with a variety of food dishes. The Pinot noir of the “great red Burgundies” tend to show its best with more spice and earthy complexity that pair with heartier dishes.

What you should do instead: So, yes, discover Cru Beaujolais. They are so much better than Beaujolais Nouveau which is, sadly, the extent of most people’s experience with Beaujolais. But don’t try to paint them as something that they’re are not. It’s like appreciating the skill and talents of George Clooney without trying to paint him as Laurence Olivier. They both have their charms but they’re different.

10.) ‘Grand Vin’ on a Bordeaux

Some estates, like the First Growth Chateau Margaux, even make a “Third Wine” which in exceptional vintages like 2010 can be outstanding values. I was very excited to see this wine on the list of Goodman’s Steakhouse in London.

The assumption: “The best berries of every vintage are selected into this wine — it’s not one of the leftover sell-offs. This is important because in many years in France, the lesser berries are very disappointing. Sometimes the Grand Vin is very expensive, but you can get many under $25.”

Err….no: Why in the world would they use a bottle of Chateau Latour (average retail price $792 a bottle) to illustrate this point, I have no clue. This slide kind of seems like it wants to be a continuation of the Cru Bourgeois tidbit from #5 but is even less useful. Yes, the Grand Vin is a producer’s “top wine” but that tells you nothing about the quality of the producer themselves.

What you should do instead: Ironically, the “leftover sell offs” that Kleinhans poo poos is often a great value. Rather than “sell off” the grapes, many high quality producers will make a Second Wine from lots that have been declassified. Different producers have different guidelines but the basic idea behind a producer doing this is that they only want to make a limited quantity of the Grand Vin, of which they want to be extremely selective in making sure that only the cream of the crop is used. This doesn’t meant that the declassified lots are “very disappointing”, they’re just not the very best. These second wines are still being sourced from many of the same vineyards and terroir of the Grand Vin and handled with the same amount of exceptional care and skill.

It’s like the difference between getting a ‘A+’ on the report card in school versus a ‘B+’. They’re both very good grades, just one’s better. While mom and dad may have given out $5 for each “A” on the report card and $3 for each “B” so too do we see a difference in the pricing between the top tier Grand Vin and the top value Second Wine. For example, the 2010 Chateau Margaux (incredible wine, incredible vintage) earned numerous 100 point accolades and averages for over a $1000 a bottle. The second wine, the 2010 Pavillon Rouge, also earned lovely accolades such as 96 points from James Suckling and a pair of 94 points from Wine Enthusiast and Wine Spectator. That wine retails for an average around $195 a bottle. But, again, this is where knowing the producer is key if you want to get the best value. In many cases the second wine of an outstanding producer, for less price, is better than the Grand Vin of a sub-par one.

Moral of the Story (Part II)

There are no “silver bullets” or “magical words” that will pick out for you the best bottle for the money each and every time, only magic beans that give you part of the story. If you really want to increase your odds of getting the right bottle for you, the best thing you can do is simply ask about the wine–get more of the story. Whether it is a restaurant sommelier or a store retail clerk, ask them what they think about the wine and how it matches up with the kind of wines that you personally enjoy.