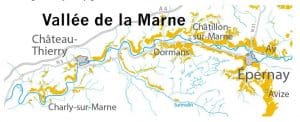

We’ve covered the exceptions of the Montagne de Reims and Vallée de la Marne in parts I and II of this series. Now we turn our focus to the Côte des Blancs, the “hill of whites.”

Coat of Arms of the Grand Cru village of Avize. Note the color of the grapes.

It’s almost an understatement to say that this region is universally known for world-class Chardonnay. Of all the superlatives in Champagne, this is one you can absolutely take to the bank.

So pretty short article today, eh?

Well, not quite.

I’ve still got a few geeky tricks up my sleeve–including one notable exception. But more importantly, we’re going to look at the why behind the superlative.

Why Chardonnay? And why does no one talk about planting Pinot noir here? After all, it’s also a highly prized noble variety. So why is the entire Côte des Blancs region planted to 85% Chardonnay with only 7% Pinot noir?

To answer that, we need to cut deep as we look at the sub-regions of the Côte des Blancs.

Côte des Blancs (Heart of the region with the Grand Crus and all but one premier cru.)

Val du Petit Morin (The exception worth knowing about.)

Cote de Sézanne

Vitryat

Montgueux

That last one, Montgueux, is a bit of a wild card. I can see why it is officially grouped with the Côte des Blancs. But it’s in the Aube department, just west of Troyes. In comparison to the other subregions, Montgueux is 60 km away from Sézanne and over 100km away from Avize. So I’m going to put this one aside till Part IV.

Map of the Côte des Blancs from the UMC website

A couple more whetstones.

In Part I & II, I gave a few recommendations of helpful wine books and study tools. Today, I’ll add two more that I’ll be relying heavily on for this article.

Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay’s The Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste – This is the perfect companion to Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson’s World Atlas of Wine. While the latter goes into geeky encyclopedic detail, The Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste ties those details back to how they directly influence what ends up in your glass. Great book for blind tasting exams.

James E. Wilson’s Terroir: The Role of Geology, Climate, and Culture in the Making of French Wines – Not going to lie. This is not a bedtime read. Well, it is if you want a melatonin boost. While chockful of tremendous insight, this is a very dense and technical book. You want to treat this more as an encyclopedia–looking up a particular region–rather than something you go cover to cover with. But if you want to sharpen your understanding of French wine regions, it’s worth a spot on your bookcase. (Especially with used copies on Amazon available for less than $10)

When you think of the Côte des Blancs, think about the Côte d’Or.

Vineyards in the northern Grand Cru of Chouilly with the Butte de Saran in the background.

The Côte des Blancs is essentially Champagne’s extension of the Brie plateau (yes, like the cheese). Over time it has eroded and brought the deep chalky bedrock to the surface. Like the Côte d’Or, both the heart of the Côte des Blancs and Cote de Sézanne have east-facing slopes capped by forests with a fertile plain at the bottom.

This prime exposure is the first to receive warmth from the early morning sun. During the cold spring nights of flowering (after bud break), Chardonnay is most vulnerable as the earliest bloomer. It needs to get to that warmth quickly for successful pollination.

It’s a similar reason why growers in the Côte des Blancs avoid planting near the very top of the slope where there is more clay. The soils here are cooler and don’t heat up as quickly. Plus, being so close to the misty forest cap encourages wetter conditions that promote botrytis. As we covered in Part II, both Chardonnay and Pinot noir are quite sensitive to this ignoble rot.

Echoing back to Burgundy, we see that the most prized plantings of Chardonnay (notably the Grand Cru villages) in the Côte des Blancs are midslope. In the sparse areas where we do find Pinot noir and Pinot Meunier, it’s usually the flatter, fertile plains that have deeper topsoils.

The Tiny Exceptions.

This is the case with the premier cru village of Vertus. While still 90% Chardonnay, the southern end of the village sees more clay and deeper topsoils as the slope flattens and turns westward. This encourages a little red grape planting with fruit from the village going to houses like Duval-Leroy, Larmandier-Bernier, Delamotte, Louis Roederer, Moët & Chandon and Veuve Clicquot.

The village of Grauves is also an interesting case. In his book, Champagne, Peter Liem argues that this premier cru should actually be part of the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay. Looking at a good wine map, you can easily see why. It’s on the other side of the forest cap from the rest of the Côte des Blancs villages–opposite Cramant and Avize. Here most all the vineyards face westward. While Chardonnay still dominates (92%), we see a tiny amount of Meunier (7%) and Pinot noir (1%) creep in.

Likewise, in Cuis–where vineyards make an almost 180 arch from Cramant and Chouilly to Grauves–we see a range of exposures that adds some variety to the plantings (4% red grapes). The home village of Pierre Gimonnet, Cuis is still thoroughly Chardonnay country as a fruit source for Billecart-Salmon, Bollinger and Moët & Chandon.

This video (3:08) from Champagne Pierre Domi in Grauves has several great aerial drone shots of the area.

But why not more Pinot noir?

For years, plantings of Chardonnay have steadily increased. Part of this has been driven by market demand–particularly with the success of Blanc de Blancs Champagne. Another reason could be climate change with the search for more acidity and freshness.

So you could say, why bother planting Pinot noir when you have such great Chardonnay terroir?

But there are other viticultural reasons for the Côte des Blancs to flavor Chardonnay over Pinot noir. For one, despite the topographical similarities to the Côte d’Or (and Côte de Nuits), the soil is much chalkier in the Côte des Blancs. While Pinot noir likes chalk, it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

Chalk has many benefits, but it also has a significant negative.

It’s high calcium content and alkaline nature encourages reactions in the soil that make vital nutrients like iron and magnesium scarce. Both are needed for chlorophyll production and photosynthesis. A lack of these nutrients can lead to chlorosis–of which Pinot noir is particularly susceptible.

The effects of chlorosis can be seen in the yellowing of leaves due to lack of chlorophyll. Considering that all the sugars that go into ripening grapes come from the energy production of photosynthesis, this isn’t great for a wine region that often teeters on the edge of ripeness–especially with Pinot noir.

There is also more lignitic clay down in the Val du Petit Morin and Marne Valley.

This picture is from the website of Champagne Oudiette who has vineyards in both areas.

As James Wilson notes in Terroir, the “magical ingredient” to help balance these soils is lignite. In Champagne, lignitic clays are known as cendres noires or “black ashes.” Essentially compressed peat mixed with clay, the cendres noires helps hold these critical nutrients in the soil.

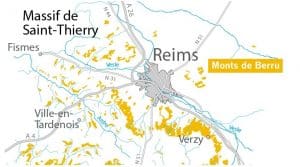

The Montagne de Reims, particularly around Bouzy and Ambonnay (which are home to quarries of cendres noires), naturally has more of this “magical ingredient.” While chlorosis can be an issue for Chardonnay as well–requiring the use of fertilizers or cendres noires to supplement the soil–the risk isn’t as grave.

However, there is one red grape stronghold in the Côte des Blancs.

Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the Val du Petit Morin.

While still paced by Chardonnay (52%), this is the one area of the Côte des Blancs where you’ll find villages dominated by something else. If you have a good wine map (and read Part II of our series), you’ll see why.

Cutting between the Côte des Blancs and Côte de Sézanne, the Petit Morin is an east-west river that brings with it a fair amount of frost danger. Also, like the Marne, we see more diversity in soils with alluvial sand and clay joining the chalk party.

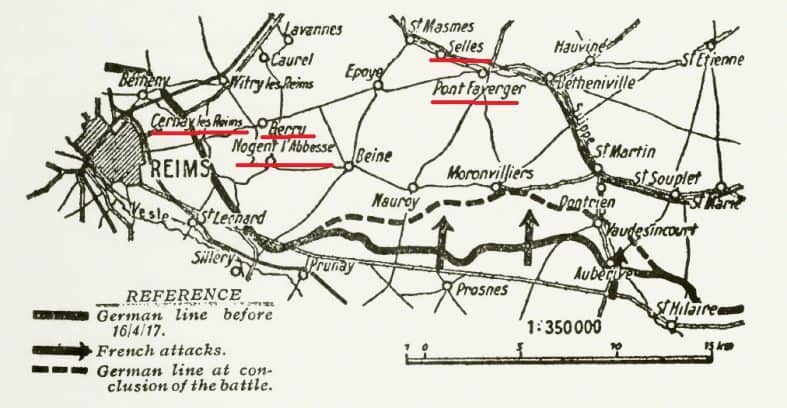

The Petit Morin also flows through the marshes of Saint-Gond–which played a key role in the First Battle of the Marne during World War I. Swampy marshland (and the threat of botrytis) frustrates Chardonnay and Pinot noir just as much as it frustrated the Germans.

Among the notable villages here:

Congy– (50% Pinot Meunier/28% Chardonnay) The home village of the renowned grower Ulysse Collin. This estate was one of the first to bring attention to the Val du Petit Morin.

Étréchy – The only premier cru outside of the heart of the Côte des Blancs. Neighboring both Vertus and Bergères-lès-Vertus (so away from the river), this follows the narrative of many of its 1er and Grand Cru peers by being 100% Chardonnay.

Villevenard – (53% Pinot Meunier/37% Chardonnay) Along with Sainte-Gemme in the Vallée de la Marne Rive Droite, Leuvrigny in the Rive Gauche and Courmas in the Vesle et Ardre of the Montagne de Reims, this autre cru is a source of Meunier for Krug. It’s also the home of Champagne Nominé Renard whose relatives help pioneer Champagne production in the village.

The video below (6:15) tells a little bit about their story with views of the vineyards starting at the 2:14 mark. You can see here how different the soils look compared to the heart of the Côte des Blancs with the Grand Crus.

Côte de Sézanne

Just about every wine book will describe the Côte de Sézanne as a “warmer, southern extension of the Côte des Blancs.” The region certainly upholds the Chardonnay banner with the grape accounting for more than 75% of plantings.

But most of those wine books are going to ignore the Val du Petit Morin mentioned above. And they’re certainly going to ignore the influence that the swampy Marais Saint-Gond has on the northern villages of the Côte de Sézanne. Here we see villages like Allemant and Broyes, which, while still Chardonnay dominant, have more diversity than the near monovarietal heart of the Côte des Blancs.

Even going south to the namesake autre cru of Sézanne, we see nearly a third of the vineyards devoted to red grapes. Here, further away from the Val du Petit Morin, we still have a fair amount of clay in the soil. This, combined with the warmer climate, shapes not only the Chardonnays of the Côte de Sézanne (riper, more tropical) but also paves the way for red grape plantings.

In the village of Montgenost, south of Sézanne, we get firmly back to Chardonnay country (94%). This is the home turf of the excellent grower Benoît Cocteaux. While the video below (2:12) is in French, it does have some great images of the area.

Vitryat

If the Côte de Sézanne is the southern extension of the Côte des Blancs, then the Vitryat is its southeastern arm. And it’s even more of a “mini-me” than the Sézannais.

Of the 15 autre crus here, four are 100% Chardonnay-Changy, Loisy-sur-Marne, Merlaut and Saint-Amand-sur-Fion. Another four have 99% of their vineyards exclusive to the grape with no village having less than 95% Chardonnay. Yeah, it’s pretty much a white-out here.

Among the teeniest, tiniest of exceptions worth noting are:

Glannes – 97% Chardonnay/3% Pinot noir with fruit going to Moët & Chandon.

Vanault-le-Châtel – 99.1% Chardonnay, 0.3% Pinot noir with 0.6% other (Pinot gris, Pinot blanc, Arbane and/or Petit Meslier). Louis Roederer purchases fruit from here.

Vavray-le-Grand – 99% Chardonnay/1% Pinot noir. A source of fruit for Billecart-Salmon.

Takeaways

The village of Montgueux (which we’ll cover in Part 4) shares the same Turonian era chalk as the Vitryat sub-region. Both are different from the Campanian chalk of the Côte des Blancs and Côte de Sézanne.

Even as the Côte des Blancs exhibits the supreme superlative in its Chardonnay-dominance, looking under the covers always reveals more.

But the biggest takeaway that I hope folks are getting from this series is that both the exceptions and superlatives make sense. The combination of soils, climate and topography lend themselves more to some grape varieties over the other.

This is the story of terroir. The problems come when we start thinking of regions as monolithic and accepting, prima facie, the butter knife narrative about them. Even when the superlatives are overwhelmingly true (i.e., the Côte des Blancs is known for outstanding Chardonnay), the reasons why cut deeper.

We’ll wrap up this series with a look at the Côte des Bar.