Vineyards of Ch. Gazin in Pomerol.

After striking out completely on our last visit to Pomerol where we explored the 2017 Bordeaux Futures offers for Ch. Clinet, Clos L’Eglise, L’Evangile and Ch. Nenin, we head back there to see if maybe, possibly, somehow there will be anything resembling a decent value in the offers from Vieux Chateau Certan, La Conseillante, La Violette and L’Eglise Clinet.

Or maybe I will just end up buying more 2014s? Though that vintage has been more hit or miss for me in Pomerol than it has been in St. Emilion and on the Left Bank.

While I did pick up some Pomerols during the 2015/2016 campaigns, rising prices and difficulties in finding good, consistent values has lead to this appellation taking up an ever shrinking amount of space in my cellars.

But, hey, it never hurts to keep exploring. So let’s see what we’ve got here.

First time visitors are encouraged to check out the first Bordeaux Futures 2017 post in the now 13 article series that covered the offers of Palmer, Valandraud, Fombrauge and Haut-Batailley and laid out the groundwork for our approach with buying 2017 Bordeaux Futures.

So far we’ve reviewed the 2017 offers of more than 50 Bordeaux estates and compared them to the current retail pricing over previous vintages. You can check these out and more via the links at the bottom of the page.

Now onto the offers.

Vieux Chateau Certan (Pomerol)

Some Geekery:

Clive Coates notes in Grand Vins that the name “Certan” was originally spelled Sertan and likely derived from an old Portuguese word for “desert”. It was reported that when Portuguese settlers were traveling through the area in the 12th century that they found the soils to be so poor and arid that they thought little could grow successfully there.

Vines were planted by at least the 18th century when the property came under the ownership of the De May family who were merchants of Scottish origins. The De Mays also owned neighboring Ch. Nenin until 1782 when it was sold so that the family could focus all its attention on Vieux Chateau Certan.

After the French Revolution, the property was split among the heirs with one part becoming what is now Ch. Certan de May. The other part that remained Vieux Chateau Certan would stay in the De May family until 1858 when it sold to a Parisian businessman, Charles de Bousquet. Unfortunately soon after the acquisition, the ravages of phylloxera hit and the estate entered a period of several decades of financial hardships.

The tower of Troplong-Mondot in St. Emilion which Georges Thienpont sold to focus on Vieux Chateau Certan.

The modern history of Vieux Chateau Certan began when it was sold to a Belgian wine merchant, Georges Thienpont, who also owned the St. Emilion estate Troplong Mondot. It was Thienpoint who had the idea of using bright pink capsules so that he could easily spot bottles of Vieux Chateau Certan in his clients’ cellars.

While financial difficulties in the 1930s would cause the Thienponts to sell Troplong Mondot, the family still retains ownership of Vieux Chateau Certan today with Georges’ grandson, Alexandre, managing the estate.

In 1978, when the Loubie family was selling Ch. Le Pin, Alexandre’s father Léon was looking to buy the property and absorb its 2 hectares of vines into those of Vieux Chateau Certan. But when the pricing couldn’t be worked out, Thienpont convinced his nephew, Jacques, to purchase the estate that has now go on to achieve cult status in Bordeaux.

The 14 ha (35 acres) of vines at Vieux Chateau Certan covers 3 distinct soil types with different grape varieties planted on each type. The parcels located next to Ch. Petrus and sharing some of its famous blue clay are planted to Merlot. Here there are some plots that have been planted in 1932 and 1948, making them some of the oldest vines in Pomerol.

On the soils that are a mixture of clay and gravel, Cabernet Franc is planted and accounts for around 30% of all Vieux Chateau Certan vines. In the winery, Thienpont treats the Cabernet Franc differently than other producers by fermenting the wine at high temperatures (30C/86F) and having malolactic fermentation take place in stainless steel tanks instead of in the barrel. The amount of Cabernet Franc used in the final blend varies depending on vintage with some years like 2003 being 80% Cabernet Franc.

The parcels on red gravel are planted to Cabernet Sauvignon which account for around 5% of all the vines. All the vineyards are farmed sustainably.

The 2017 vintage is a blend of 81% Merlot, 14% Cabernet Franc and 5% Cabernet Sauvignon. Around 4000 to 5000 cases a year are produced.

Critic Scores:

97-98 James Suckling (JS), 96-98 Wine Advocate (WA), 95-97 Wine Enthusiast (WE), 94-96 Vinous Media (VM), 96-98 Jeff Leve (JL),

Sample Review:

The 2017 Vieux Château Certan is a rapturously beautiful wine. Dark, sumptuous and seamless in the glass, the 2017 is going to tempt readers early. This is the first vintage that includes a bit of young vine Cabernet Sauvignon planted in 2012 to complement the old-vine Merlot and Franc that are the core of Vieux Certan. A wine of exceptional balance and purity, the 2017 dazzles from start to finish. There is an element of tension in the 2017 that is incredibly appealing. “We are back to Bordeaux,” adds Alexandre Thienpont in reference to the personality of the year as compared to both 2016 and 2015. — Antonio Galloni, Vinous

Offers:

Wine Searcher 2017 Average: $231

JJ Buckley: $239.94 + shipping (no shipping if picked up at Oakland location)

Vinfolio: No offers yet.

Spectrum Wine Auctions: No offers yet.

Total Wine: $239.97 (no shipping with wines sent to local Total Wine store for pick up)

K&L: $239.99 + shipping (no shipping if picked up at 1 of 3 K & L locations in California)

Previous Vintages:

2016 Wine Searcher Ave: $281 Average Critic Score: 95 points

2015 Wine Searcher Ave: $330 Average Critic Score: 96

2014 Wine Searcher Ave: $190 Average Critic Score: 95

2013 Wine Searcher Ave: $156 Average Critic Score: 91

Buy or Pass?

The 2009 Vieux Château Certan rocked my world and my mouth drools at the thought of how delicious the 2003 Cabernet Franc-dominated VCC must be tasting today. But, alas, the trend of 2017 pricing that we saw in our last foray into Pomerol is still holding true here with an average price well above the comparable 2014 vintage that is still on the market.

While I have no doubt that this will probably be a tasty wine, there just isn’t the compelling value to make this a worthwhile futures purchase. Pass.

Ch. La Conseillante (Pomerol)

Some Geekery:

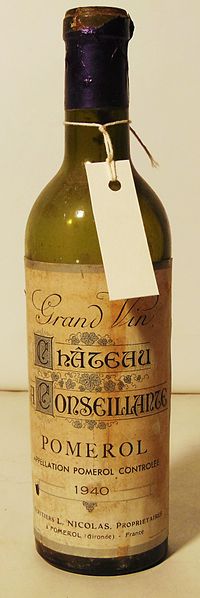

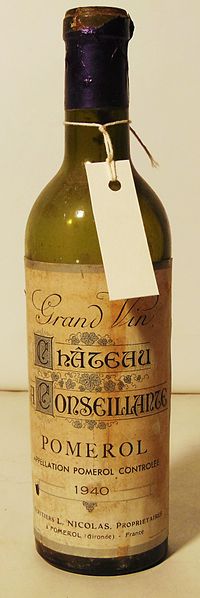

A bottle of 1940 La Conseillante with the distinctive purple capsule still visible.

La Conseillante is one of the oldest estates in Pomerol being founded in the 1730s by Catherine Conseillan, a Libournais businesswoman who was known as a dame de fer for her work in the metal industry where she sold ploughshares and wires for vine training.

For the first couple decades the vineyards were managed via a métayage system of sharecropping until 1756 when Madame Conseillan took full control of the property and built a chateau. She managed the estate until her death in 1777 when the property passed to her niece and then a succession of owners until it was purchased by the Nicolas family in 1871.

A well connected negociant family who owned Nicolas Freres, it was the Nicolas family who began using the distinctive purple capsules on the bottle. When they purchased the estate the vineyards of La Conseillante was planted to around a third Malbec, a third Merlot and a third of Cabernet vines split between Sauvignon and Franc.

The property is still owned by the Nicolas Family today. In the early 2000s, Jean-Michel Laporte was brought on as winemaker with Gilles Pauquet as a consultant. By 2013, Michel Rolland replaced Pauquet as consultant and, in 2015, Laporte left La Conseillante and was succeeded by Marielle Cazaux who used to direct the winemaking at Ch. Petit Village.

The 12 ha (30 acres) of vines are now planted to 80% Merlot and 20% Cabernet Franc with plans to increase the percentage of Cabernet Franc up to 30%. Nearly two-thirds of the vines are close to Vieux Chateau Certan and Petrus. Other parcels are close to Ch. Beauregard, L’Evangile, Petit Village and the St. Emilion border with Cheval Blanc. Many of the parcels are farmed organically.

The 2017 vintage is a blend of 85% Merlot and 15% Cabernet Franc. Around 4,500 cases a year are produced though with the frost damage of 2017, production will be lower for this year.

Critic Scores:

95-97 WA, 95-97 WE, 94-95 JS, 93-95 VM, 95-97 JL, 94-96 Jeb Dunnuck (JD)

Sample Review:

With 15% lost to frost (just 1.5ha entirely lost), the final yield was 34hl/ha, with no second generation fruit in the wine. It’s an excellent take on the vintage, the austerity coming through on the attack before it opens to a wonderfully smoky mid-palate with loganberry and blackberry fruit, showing real fullness and volume. This has texture, structure and good aromatics, with a great sense of energy and persistency. The plot affected by the frost was a Duo parcel, so they will make a small amount of second wine but not as much as usual, and the overall production will be 85% grand vin. In organic conversion. 70% new oak. (94 points) — Jane Anson, Decanter

Offers:

Wine Searcher 2017 Average: $165

JJ Buckley: $169.94 + shipping

Vinfolio: No offers yet.

Spectrum Wine Auctions: $1,019.94 for minimum 6 bottles + shipping (no shipping if picked up at Tustin, CA location)

Total Wine: $169.97

K&L: $169.99 + shipping

Previous Vintages:

2016 Wine Searcher Ave: $213 Average Critic Score: 95 points

2015 Wine Searcher Ave: $192 Average Critic Score: 94

2014 Wine Searcher Ave: $106 Average Critic Score: 93

2013 Wine Searcher Ave: $93 Average Critic Score: 91

Buy or Pass?

My only experience with La Conseillante has been with their very delicious 2014 release. While I would certainly like to explore more of their bottlings, at the prices being asked for their 2017 futures I’m going going to Pass and look into stocking up on more of the 2014.

Ch. La Violette (Pomerol)

Some Geekery:

Ch. La Violette is a relatively young estate that was founded in the late 1800s by a cooper, Ulysse Belivier. Despite a very enviable location on the plateau of Pomerol flanking Ch. Trotanoy and what is now Le Pin, the wines of La Violette were marred in obscurity until 2006 when it was purchased by Catherine Péré Vergé.

Péré Vergé, who also owned Chateau Le Gay and Chateau Montviel in Pomerol, Ch. La Graviere in Lalande-de-Pomerol and Bodega Monteviejo in Argentina, brought in her longtime consultant Michel Rolland. Over the next several vintages, the winery was renovated and all Cabernet Franc vines uprooted and replaced with Merlot.

Very labor-intensive viticulture practices were put in place with each individual vine in the tiny 1.68 ha (4 acres) estate being “manicured” by hand throughout the growing season with individual green and unripe berries removed during several passes in the vineyard after veraison. After harvest, instead of using a machine, the grapes are destemmed by hand with a very selective triage and sorting. Coupled with severe pruning in the winter months, this produces incredibly low yields that can be as low as 18 to 20 hl/ha (a little over 1 ton/acre).

Catherine Péré Vergé passed away in 2013 and today the estate is managed by her son, Henri Parent, who has also added the Pomerol estates of Ch. Tristan and Feytit-Lagrave to the family’s holdings. Michel Rolland still consults with Marcelo Pelleriti managing the winemaking.

The 2017 vintage is 100% Merlot. Only around 250 cases a year a produced.

Critic Scores:

94-96 WA, 94-95 JS, 92-94 VM, 91-94 WS, 93-95 JL, 93-96 JD

Sample Review:

The 2017 La Violette is another silky, elegant effort that has a Burgundian flare. Black cherries, blueberries, violets, white flowers, and spice characteristics all emerge from this seamless 2017 that is as classy, silky and pure as they come. Total class and up with the crème de la crème of the vintage. — Jeb Dunnuck, JebDunnuck.com

Offers:

Wine Searcher 2017 Average: $249

JJ Buckley: No offers yet

Vinfolio: No offers yet.

Spectrum Wine Auctions: No offers yet.

Total Wine: $254.97

K&L: No offers yet.

Previous Vintages:

2016 Wine Searcher Ave: $263 Average Critic Score: 93 points

2015 Wine Searcher Ave: $336 Average Critic Score: 94

2014 Wine Searcher Ave: $273 Average Critic Score: 92

2013 Wine Searcher Ave: $205 Average Critic Score: 91

Buy or Pass?

Throughout the 2017 Bordeaux Futures campaign, I’ve been pretty disciplined in only going with wines from estates that I have a track record of previously tasting and enjoying. In more stellar vintages like 2015/2016, I’m far more adventurous and open to trying new estates but in more average years like 2017 I prefer to be conservative.

I’ve bent that rule already for the 2017 Carruades de Lafite and I think I’m going to have bend this one again for the La Violette. For one, the price is compelling being under both the 2016 and 2014 vintage. But, truthfully, my prime motivator is how much of a unicorn La Violette is and this maybe one of the few opportunities I will ever get a chance to try this wine.

Beyond just how scarcely limited it is, the only time that I’ve ever seen La Violette has been on restaurant wine lists topping over $800 a bottle. That is far more riskier of a venture for me to try a new estate versus buying a bottle as a future.

More ideally, I would want to spend the $9-14 extra to get the better 2016 vintage but I didn’t see any future offers for this last year so I would have to do some investigating to see how many of the offers for the 2016 on Wine Searcher are legit. But right now I’m inclined to go with the sure thing and Buy the 2017 just so I can bag this unicorn.

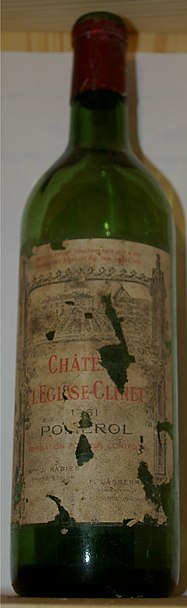

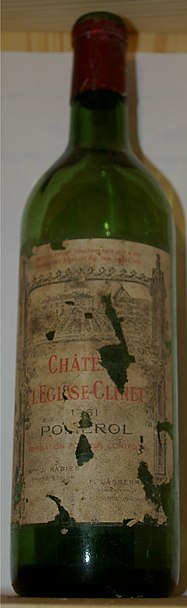

A bottle of 1961 L’Eglise Clinet made by Pierre Lasserre of Clos Rene.

Ch. L’Eglise Clinet (Pomerol)

Some Geekery:

The origins of L’Eglise Clinet date back to 1803 when Jean Rouchut first purchased some lands near the church (église) and cemetery for a vineyard. 1882, his descendants purchased vineyards belonging to the Constant family of Ch. Clinet and entered into a joint venture that would be known as L’Eglise Clinet.

In the early 20th century, the owners took a very hands off approach to winemaking–first by entering a leasing agreement in 1914 with a negociant firm to make the wine and then formulating a sharecropping arrangement with Pierre Lasserre of Clos Rene in 1942 that would last for more than 40 years.

In 1983, Denis Durantou took over his family’s estate and today still manages L’Eglise Clinet along with Saintayme in St. Emilion, Ch. Montlandrie in Cotes de Castillon and Ch. Cruzelles and Ch. Chenade in Lalande-de-Pomerol.

Much of L’Eglise Clinet’s 4.4 ha (11 acres) of vines escaped the devastating 1956 frost which means that L’Eglise has some of the oldest vines in Pomerol with more than a quarter being over 75 years of age. Two parcels of old vine Cabernet Franc located near the cemetery were planted in the early 1930s.

The current ratio of planting is 85% Merlot, 14% Cabernet Franc and 1% Malbec, however, all of the Malbec is actually part of a field blend interspersed with the old vines and is gradually being replaced by massale selection of Cabernet Franc. Many of the parcels are farmed organically.

The 2017 vintage is a blend of 90% Merlot and 10% Cabernet Franc. Around 1000 to 1500 cases a year are produced.

Critic Scores:

97-98 JS, 96-98 WA, 95-97 VM, 92-95 WS, 94-96 JL, 92-94 JD

Sample Review:

Black core with purple crimson rim. A hint of oak char on the nose but underneath that is pure black fruit and a creamy character. Smooth and rounded on the palate, the fruit and the oak already well melded. The finish is darker and more savoury, the oak char closing the circle. But the harmony is very good. Not as charming as La Petite Église but longer-term in potential. (17 out of 20) — Julia Harding, JancisRobinson.com

Offers:

Wine Searcher 2017 Average: $231

JJ Buckley: $239.94 + shipping

Vinfolio: No offers yet.

Spectrum Wine Auctions: No offers yet.

Total Wine: $239.97

K&L: $249.99 + shipping

Previous Vintages:

2016 Wine Searcher Ave: $313 Average Critic Score: 93 points

2015 Wine Searcher Ave: $290 Average Critic Score: 95

2014 Wine Searcher Ave: $211 Average Critic Score: 94

2013 Wine Searcher Ave: $177 Average Critic Score: 92

Buy or Pass?

L’Eglise Clinet is another Pomerol estate that I have no previous track record with so that is one strike against this offer for me. But, unlike La Violette, the pricing for the 2017 compared to other vintages is not compelling enough to come close to enticing me to bite here. Pass.

More Posts About the 2017 Bordeaux Futures Campaign

Why I Buy Bordeaux Futures

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Langoa Barton, La Lagune, Barde-Haut, Branaire-Ducru

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Pape Clément, Ormes de Pez, Marquis d’Alesme, Malartic-Lagraviere

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Lynch-Bages, d’Armailhac, Clerc-Milon and Duhart-Milon

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Clos de l’Oratoire, Monbousquet, Quinault l’Enclos, Fonplegade

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Cos d’Estournel, Les Pagodes des Cos, Phélan Ségur, Calon-Segur

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Clinet, Clos L’Eglise, L’Evangile, Nenin

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Malescot-St.-Exupéry, Prieuré-Lichine, Lascombes, Cantenac-Brown

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Domaine de Chevalier, Larrivet Haut-Brion, Les Carmes Haut-Brion, Smith Haut Lafitte

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Beychevelle, Talbot, Clos du Marquis, Gloria

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Beau-Séjour Bécot, Canon-la-Gaffelière, Canon, La Dominique

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Carruades de Lafite, Pedesclaux, Pichon Lalande, Reserve de la Comtesse de Lalande

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Montrose, La Dame de Montrose, Cantemerle, d’Aiguilhe

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Clos Fourtet, Larcis Ducasse, Pavie Macquin, Beauséjour Duffau-Lagarrosse

*Bordeaux Futures 2017 — Kirwan, d’Issan, Brane-Cantenac, Giscours