January and February are the doldrums of winter. They don’t feature the festivities of December–only snow, freezing cold and dark gray days. It just plain sucks. But eventually March and spring will be on the horizon.

One of the trademark clues of Gruner Veltliner in a blind tasting is the presence of white pepper. This comes from the compound rotundone that forms naturally in the grapes.

While we’re popping vitamin D supplements and counting down the days till pitchers and catchers report, let’s take a look at a few new and upcoming wine books.

The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting, Third Edition by Neel Burton (Paperback release February 3rd, 2019)

I own the original 2014 edition of Burton’s book that he did with James Flewellen. It is handy but, in all honesty, I’m not sure it’s correctly named.

What I had initially hoped for was a book that would teach you some of the tips and tricks to blind tasting. Like for instance, if you detect black or white pepper in a wine, you should know that is caused by the compound rotundone.

There are only a handful of grape varieties that contain this compound–most notably Syrah, Grüner Veltliner, Mourvèdre, Petite Sirah and Schioppettino. Detecting this during a blind tasting flight is a huge clue. Furthermore, anecdotal and some scientific analysis has shown that cooler climates and vintages increase the concentration of rotundone and “pepperiness” of the wine. This can be another clue in nailing down wine region and vintage.

That was the kind of insight and details that I was hoping for with Burton and Flewellen’s book. You get a little but not quite to the extent I was looking for in a book marketing itself as a blind tasting guide. Instead, The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting tilts more to the “Guide to Wine” side offering a (very well done) overview of the major regions and wines of the world.

Chapter 4 does walk you through the blind tasting process and the Appendix gives a “crib sheet” of common flavors and structure which is very useful. But that’s about it.

However, I’m still buying this new edition

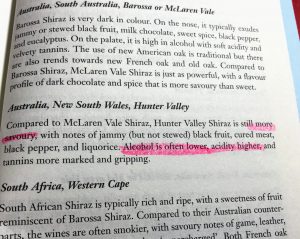

Example of the blind tasting “crib sheets” in the appendix of the first edition of The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting.

That’s because it’s an excellent guide to wine that is similar to Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay’s The Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste: A Field Guide to the Great Wines of Europe. Burton’s book doesn’t list benchmark producers like Parr’s book does but they both highlight the distinction of terroir that shows up in the wines from various regions. They’re a bit like condensed versions (362 and 352 pages, respectively) of Karen MacNeil’s Wine Bible (1008 pages) with a bit more focus on the taste profiles and terroir of each region.

I’ve gotten plenty of good use out of the first edition of The Concise Guide to Wine and Blind Tasting to make the new version a worthwhile investment. Plus, it is possible that this updated version will go more into those blind tasting details that I crave.

The Chinese Wine Renaissance: A Wine Lover’s Companion by Janet Z. Wang (Hardcover released on January 24th, 2019)

Back in November, I highlighted Loren Mayshark’s Inside the Chinese Wine Industry which has been a great read. As I noted in that edition of Geek Notes, China is a significant player on the global wine market. While the interest of the industry has been mostly on their buying power, the large size and diverse terroir of mainland China offer exciting potential for production.

A bronze Gu, or ceremonial wine vessel, from the Shang Dynasty dating to the 12th or 11th century.

It is in the best interest of any wine student to start exploring Chinese wine. I recently got geeky with Grace Vineyard Tasya’s Reserve Shiraz and can’t wait to find more examples. In addition to Mayshark’s book, Suzanne Mustacich’s Thirsty Dragon: China’s Lust for Bordeaux and the Threat to the World’s Best Wines has been highly informative as well.

But both of those were written by non-native writers. That is what make’s Janet Z. Wang’s Chinese Wine Renaissance intriguing. Wang spent her childhood in China before moving to the United Kingdom as a teenager. There she studied Chinese history and culture before developing an interest in wine while at Cambridge.

Now she runs her blog, Winepeek, and contributes to Decanter China. In between her writings, she teaches masterclasses on Chinese wine.

On her blog, she has a slideshow with wine tasting suggestions that gives a sneak peek into what her book covers. With a foreword and endorsement from Oz Clarke, I have a feeling that Wang’s book is going to become the benchmark reference for Chinese wine.

Decoding Spanish Wine: A Beginner’s Guide to the High Value, World Class Wines of Spain by Andrew Cullen and Ryan McNally (Paperback released on January 24th, 2019)

Now granted, Costco doesn’t sell many Cremants. This might explain why the Costco Wine Blog folks were so blown away by this $20 Champagne. But compared to many Cremant de Bourgogne and Alsace in the $15-20 range, it was fairly ho-hum.

Andrew Cullen is the founder of CostcoWineBlog.com that has been reviewing wines found at Costco stores for years. While I don’t always agree with their reviews (like my contrarian take on the Kirkland Champagne) I still find the site to be an enjoyable read.

Beyond the blog, Cullen has co-authored quick (around 100 pages or so) beginner wine guides to French, Italian and now Spanish wines. He also wrote the even quicker read Around the Wine World in 40 Pages: An Exploration Guide for the Beginning Wine Enthusiast.

While these books aren’t going to be helpful for Diploma students, they are great resources for folks taking WSET Level 1 and Level 2 as well as Certified Specialist of Wine exams. I particularly liked how Decoding Italian Wine went beyond just the big name Italian wine regions such as Chianti, Brunello and Barolo to get into under-the-radar areas like Carmignano, Gavi and Sagrantino di Montefalco.

Plus for $9-10, the books are super cheap as well.

French Wines and Vineyards: And the Way to Find Them (Classic Reprint) by Cyrus Redding (Hardcover released on January 18th, 2019)

This is for my fellow hardcore geeks.

I am a sucker for reprints of classical texts. I especially adore ones featured in the bibliographies of seemingly every great wine history book. Such is the esteem that the British journalist Cyrus Redding holds among Masters of Wines like Hugh Johnson, Jancis Robinson and Clive Coates.

Redding passed in 1870 so he didn’t get a chance to witness the full scale of devastation on French vineyards caused by phylloxera.

This cartoon is from an 1890 magazine that describes the pest as “A True Gourmet” that targetted the best vineyards.

First published in 1860, French Wines and Vineyards gives a snapshot of the French wine industry in the mid 19th-century. Written just after the 1855 Bordeaux classification and only a few years before phylloxera would make its appearance in the Languedoc in 1863, Redding documents a hugely influential time in the history of French wines.

Pairing this book with a reading of the 19th-century chapters in Hugh Johnson’s Vintage and Rod Phillips’ French Wine: A History would be a fabulous idea for wine students wanting to understand this key period.

One additional tip. Hardcover editions of classic texts look nice on the shelf. But if you’re a frequent annotator like me then you probably want to go paperback. Forgotten Books released a paperback version of Redding’s work back in 2017 that you can get a new copy of for less than $12 right now.