Note: The wines reviewed here were samples.

Today is Riesling’s birthday!

We’re celebrating one of the world’s greatest wine grapes because of an important document from March 13th, 1435. In an old cellar log from 585 years ago, the estate of Count John IV of Katzenelnbogen in Hessische Bergstrasse noted the purchase of “Riesslingen” vines.

This is widely considered to be the first written account about Riesling. While Jancis Robinson pegs the date as March 3rd, 1435 in Wine Grapes and some sources say it was actually February, the trade org Wines of Germany has declared that today is as good of a day as any to give our regards to Riesling.

I’m totally down with that.

As frequent readers of the blog know, you don’t need much to convince me to drink Riesling. Besides how incredibly food-friendly it is, I absolutely adore how it expresses terroir. From fantastic Australian Rieslings coming out of Mudgee to Napa Valley and numerous Washington State examples, these wines all exhibit their own unique personalities.

Yet they’re always quintessentially Riesling–with a tell-tale combination of pronounced aromatics and high acidity.

While the details of those aromatics change with terroir, that structure of acid is tattooed in typicity. If you don’t overthink it too much with flavors that can tempt you to wonder about Pinot gris, Gruner Veltliner and even Albarino, that acid is what should bring you home to Riesling in a blind tasting. Master of Wine Nick Jackson describes this well in his excellent book Beyond Flavor (received as a sample), noting that, like Chenin blanc, the acidity of Riesling is always present no matter where it is grown.

However, while Jackson describes Chenin’s acidity as creeping up on you like a crescendo–with Riesling, it smacks you immediately like a fireman’s pole. On your palate, all the other elements of the wine–its fruit, alcohol and sugar–wrap around Riesling’s steely acidity. Jackson’s firepole analogy is most vivid when you’re tasting an off-dry Riesling because while you can feel the sense of sweetness ebb, like a fireman sliding down, that acid holds firm and doesn’t move.

Seriously, next time you have a glass of Riesling, hold it in your mouth and picture Jackson’s vertical firepole. It will really change your blind tasting game.

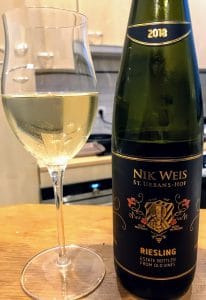

And for some great benchmark bottles to try those skills out on, may I suggest the geeky good wines of Nik Weis St. Urbans-Hof in the Mosel?

The Background

Glass window feature of St. Urban at a church in Deidesheim.

Along with his wife, Daniela, Nik Weis is a third-generation winegrower based in the middle Mosel village of Leiwen. His family’s estate, St. Urbans-Hof, was founded by his grandfather, Nicolaus Weis, after World War II. Named after the 4th-century patron saint of winegrowers who hid in vineyards to escape persecution, Weis’ family estate covers 40 hectares along the Mosel and its southern tributary, the Saar.

Many of these plots, including choice plantings in the villages of Ockfen and Wiltingen in the Saar and Piesport in the Middle Mosel, were acquired by Nik’s father, Hermann Weis.

Hermann was also the notable pioneer of Riesling in Canada. Bringing some of his family’s unique proprietary clones of Riesling to the Niagara Pennisula, Weis founded St. Urban Vineyard in the 1970s. Now known as Vineland Estates Winery, cuttings of the Weis clone Riesling from the original vineyard has been used to spread the variety all across Canada. The clones are also used in American vineyards–where they are known as Riesling FPS 01.

But the Weis family’s influence is also felt keenly in Germany as the keeper of the “Noah’s Ark of Riesling.” In his book, Riesling Rediscovered, John Winthrop Haeger notes that the Weis Reben nursery is one of the most renowned private collections of massale selected Riesling clones around. Founded by Weis’ grandfather, the source for much of the bud wood is the family’s treasure trove of old vine vineyards going up to 115 years of age.

Moreover, Master of Wine Anne Krebiehl notes in The Wines of Germany that without the efforts of Weis and his vineyard manager, Hermann Jostock, much of the genetic diversity of Mosel Riesling would have been lost.

Vineyards and winemaking

Depending on the vintage, Nik Weis can make over 20 different Rieslings ranging from a sparkling Brut to a highly-acclaimed trockenbeerenauslese. He also grows some Pinot noir, Pinot gris and Pinot blanc as well.

Nik Weis’ wealth of old vine vineyards makes it easy for him to make this stellar bottle for less than $20.

The family estate covers six main vineyards–three in the Mosel that all hold the VDP’s highest “Grand Cru” designation of Grosse Lage. When these wines are made in a dry style, they can be labeled as Grosse Gewächs or “GG.” These vineyards include:

Laurentiuslay, planted on gray Devonian slate in the village of Leiwen with vines between 60-80 years old.

Layet, planted on gray-blue slate in the village of Mehring with vines between 40-100 years old.

Goldtröpfchen, planted on blue slate in the village of Piesport with vines between 40-100 years old.

Saar Estates.

Along the Saar, Weis has two vineyards with Grosse Lage status and one with the “premier cru-level” Ortswein status (Wiltinger). Compared to the greater Mosel and the Ruwer, the Rieslings from the Saar tend to have higher acidity because this region is much cooler.

In The Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste (another must-have for wine students), Master Sommelier Rajat Parr and Jordan Mackay note that despite its more southerly location, the wider Saar Valley acts as a funnel bringing cold winds up through the valley. However, those vineyards closer to the river benefit from enough moderating influence to ripen grapes consistently for drier styles while vineyards further inland tend to be used for sweeter wines.

Bockstein, planted on gray Devonian slate in the village of Ockfen with vines between 40-60 years old.

Saarfelser, planted on red slate and alluvial soils in the village of Schoden with vines between 40-60 years old.

Wiltinger, planted on red slate in the village of Wiltigen with vines dating back to 1905.

As a member of the German FAIR’N GREEN association, Weis farms all his family’s vineyards sustainably. To help reflect the individual terroir of each plot, Weis uses native ambient yeast for all his fermentations.

The Wines

2016 Bockstein Spatlese (WS Average $27)

This was my favorite of all the wines. High-intensity nose of golden delicious apples, apricot and peach with some smokey flint.

On the palate, this wine was extremely elegant with 8% ABV that notches up to medium-minus body with the off-dry residual sugar. However, the high acidity balances the RS well and introduces some zesty citrus peel notes to go with the pronounced tree and stone fruit. Long finish lingers on the subtle smokey note.

2017 Goldtröpfchen Spatlese (WS ave $32)

Medium-plus intensity nose with riper apples and apricot fruit. It is also the spiciest on the nose with noticeable ginger that suggests some slight botrytis.

On the palate, while medium-sweet, it tasted drier than I expected from the nose. This wine spent some time in neutral (5+-year-old) oak, which added roundness. That texture consequently helps to make this 10.5% ABV Riesling feel more medium-bodied. Moderate length finish is dominated by the primary fruit, but I suspect that this wine will develop into something very intriguing.

2018 Wiltinger Alte Reben Riesling (WS ave $18)

It’s crazy to think of drinking century-plus old vines for only around $18.

Sourced from the Weis family’s oldest vines that date back to 1905, this is an insane value for under $20.

High-intensity nose, this is very floral with lilies and honey blossoms. A mix of citrus lime zest and green apples provide the fruit.

On the palate, there is a slight ginger spice that emerges despite it tasting very dry and not something that I would suspect with botrytis. Still well balanced with high acidity that enhances the fruit more than the floral notes from the nose. Long finish is very citrus-driven and mouthwatering.

2018 Old Vine Estate Riesling (WS ave $17)

Another very excellent value sourced from low yielding vineyards between 30-50 years of age.

High-intensity nose with white peach and apricots as well as minerally river stones. This also has some petrol starting to emerge.

On the palate, the stone fruits continue to dominate with a little pear joining the party. Off-dry veering towards the drier side of that scale. The high acidity makes the 11% alcohol feel quite light in body. Moderate finish intensifies the petrol note–which I really dig.

2018 Mosel Dry Riesling (WS ave $15)

Medium-plus intensity nose. Very citrusy with ripe Meyer lemons. In addition, some apple and honey blossoms emerge to complement it.

On the palate, the lemons still rule the roost with both a zest and ripe fleshy depth. The ample acidity makes the wine quite dry and also introduces some minerally salinity as well. At 12% alcohol, this has decent weight for food-pairing but still very elegant. Moderate length finish stays with the lemony theme.

Bonus Geekery

On YouTube, Kerry Wines has a short 1:37 video on St. Urbans-Hof. It includes some winery views as well as gorgeous vineyard shots that surprised me. While you certainly see those classic steep Mosel slopes, there’s also much flatter terrain as well. I haven’t had the privilege yet to visit the Mosel but will certainly need to check that out.

Going to need

Going to need