Food & Wine recently published an article by wine educator and “prophet” Jonathan Cristaldi titled “Pop These 25 Bottles and Become a Champagne Master”.

Food & Wine recently published an article by wine educator and “prophet” Jonathan Cristaldi titled “Pop These 25 Bottles and Become a Champagne Master”.

The article had so many mistakes (some glaringly obvious) that it made my head hurt.

While I wholeheartedly support any message that begins with “Pop these bottles…”, if you don’t want to look like a bloody fool to your friends, let me tell you some of the things you SHOULDN’T take away from Cristaldi’s list.

1.) Veuve Clicquot did not develop techniques to control secondary fermentation. Nor did they perfect the art of making Champagne. (Intro)

Oh good Lordy! At least Cristaldi later redeemed himself a bit by accurately noting that Dom Perignon didn’t invent Champagne. Instead, the good monk spent his entire career trying to get rid of the bubbles. But this is a whopper of marketing BS to start an article.

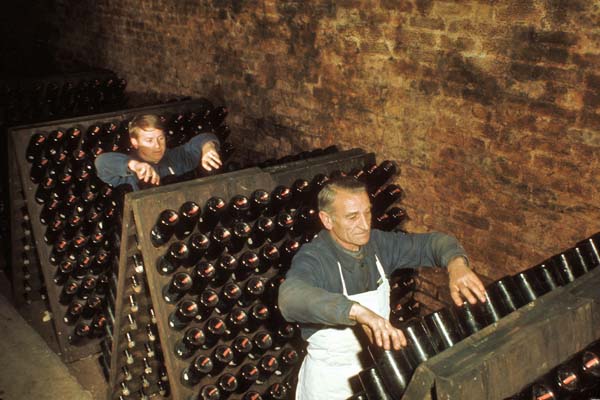

First off, let’s give Veuve Clicquot due credit for what her and her cellar master, Anton Mueller, did accomplish. From 1810 to 1818, they developed the technique of riddling to remove the dead sediment of lees leftover from secondary fermentation. This helped produce clearer, brighter Champagnes. Important, yes. But even this technique wasn’t perfected at Veuve Clicquot. It was a cellar hand from the Champagne house of Morzet and M. Michelot who perfected the pupitre (riddling rack) that truly revolutionized Champagne production.

Furthermore, riddling has nothing to do with controlling secondary fermentation. It merely deals with the after-effects that happen months (usually years) after secondary fermentation is completed.

A Toast to a Team Effort

Pasteur’s work detailing the role of yeast in fermentation and Jean-Baptiste François’ invention to precisely measure how much sugar is in wine, contributed far more to the Champagne’s industry efforts to “control secondary fermentation” than a riddling table did.

Credit for understanding the secondary fermentation in sparkling wine goes to Christopher Merret. In 1662, he delivered a paper in London on the process of adding sugar to create gas in wines. But this process was fraught with risks. Regularly producers would lose a quarter to a third of their production due to exploding bottles. It was challenging figuring out how much sugar was needed to achieve the desired gas pressure.

The major breakthrough for that came in 1836 when Jean-Baptiste François, a pharmacist and optical instrument maker, invented the sucre-oenomètre. This allowed producers to measure the amount of sugar in their wine. By the 1840s, a tirage machine was invented that could give precise amounts of sugar to each bottle to make the wine sparkle without exploding. These developments, followed by Louis Pasteur’s work in the 1860s on the role of yeast in fermentation, set the industry on the road to “perfecting the art of making Champagne.”

Truthfully, it was a team effort with many hands involved. It’s disingenuous (and, again, marketing BS) to give exorbitant credit to anyone for making Champagne what it is today.

2.) No vintage of Krug’s Grande Cuvée is the same because it is not a vintage Champagne! (Item #2 & Item #4)

Likewise, Dom Perignon is not “a blend of several older vintage base wines”. This is one of Cristaldi’s most glaring errors that he repeats throughout the article. He truly doesn’t seem to understand the differences between vintage and non-vintage Champagnes.

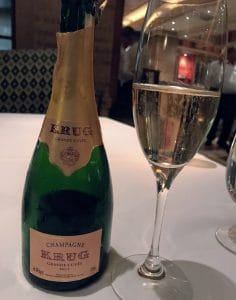

A non-vintage or “multi-vintage” Champagne.

Note the lack of a vintage year on the label.

Non-vintage Champagnes, like Krug’s Grande Cuvée, are blends of multiple years that need to be aged at least 15 months. As Cristaldi correctly notes, some examples like Krug are aged far longer and can include stocks from older vintages. But it’s still not a vintage Champagne. This is why you do not see a year on the bottle.

A vintage Champagne, such a Dom Perignon, is the product of one single year and will display that year on the bottle. By law, it needs to be aged a minimum of 36 months. You can’t “blend in” older base wines from another vintage. If you want an older base wine, you need to age the entire vintage longer.

3.) Speaking of Dom Perignon, the “6 vintages released per decade” thing hasn’t been true since the ’80s (Item #4)

Again, marketing mystique and BS.

While, yes, the concept of vintage Champagne was once sacred and reserved only for years that were truly spectacular, today it all depends on the house. Some houses, like Cristaldi notes with Salon, do still limit their vintage production to truly spectacular years. But other houses will make a vintage cuvee virtually every year they can.

Seriously…. there is so much Dom made that it is being turned into gummy bears.

In the 2000s, while the 2008 hasn’t been released yet (but most assuredly will be), Dom Perignon declared 8 out of the ten vintages. In the 1990s, they declared 7 out of 10–including the somewhat sub-par 1993 and 1992 vintages.

Now, as I noted in my post Dancing with Goliath and tasting of the 2004 & 2006 Dom Perignon, LVMH (Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy) credits global warming for producing more “vintage worthy” vintages. There is undoubtedly some truth to that. But there is also truth in the fact that LVMH can crank out 5 million plus bottles of Dom Perignon every year if they want and have no problem selling them because of their brand name.

And, if they don’t sell… well they can always make more gummy bears.

4.) Chardonnay grapes do not take center stage in every bottle of Henriot (Item #5)

The Henriot Blanc de Blancs is excellent and worth trying. But so are their Pinot noir dominant Champagnes like the Brut Souverain and Demi-Sec (usually 60% Pinot according to Tom Stevenson and Essi Avellan’s Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine) and the vintage rosé (at least 52% Pinot plus red Pinot noir wine added for color). Even Henriot’s regular vintage Champagne is usually a 50/50 blend. Again, not to discredit a great recommendation to try an awesome Champagne from a well-regarded house, but it is just lazy research for a “Champagne Master” to describe Henriot as a “Chardonnay dominant” (much less exclusive) house.

If you want to talk about Chardonnay-dominant houses, look to some of the growers based around the Grand Cru villages of Avize, Cramant and Le Mesnil-sur-Oger in the prime Chardonnay territory of the Côte des Blancs. Here you will find producers like Agrapart & Fils, Franck Bonville, Salon-Delamotte and Pierre Peters that, with few exceptions–such as Agrapart’s six grape cuvee Complantee and Delamotte’s rosé, can be rightly described as putting Chardonnay “on center stage in every bottle.”

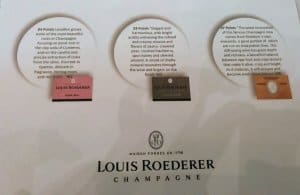

5.) No, not all the vineyards that go into Cristal are biodynamically farmed. (Item #6)

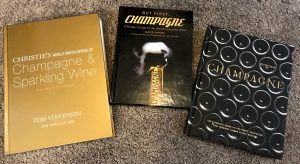

Some great resources if you don’t want to sound like an idiot when spouting off about your “mastery” of Champagne.

Update: It took almost two years but the “wine prophet” finally got one right. In December 2019, Roederer released the first Cristal sourced entirely from biodynamic grapes.

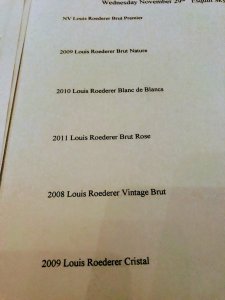

In November, I got a chance to try the new 2009 Cristal with a brand ambassador from Louis Roederer. And while I noted in my post, Cristal Clarity, that Roederer’s push towards eventually converting all their vineyards to biodynamics is impressive–right now they are only around 41% biodynamic. Of course, most of this fruit does get funneled towards their top cuvee, but in 2017, that was still just 83% of their Cristal crop.

6.) No, Taittinger’s Comtes de Champagnes are not Chardonnay only wines. (Item #11)

The Comtes de Champagne is a series of prestige vintage cuvees made by Taittinger to honor Theobald IV, the Count of Champagne. This includes a delicious Comtes de Champagne rosé that is virtually always Pinot noir dominant.

In the 1930s, Pierre Taittinger purchased the historical home of the Comtes de Champagne in Reims. Renovating the mansion, they released the first Comtes de Champagne in 1952. Yes, that was a Blanc de Blancs, but the rosé version followed soon after in 1966. While there are some vintages where only one style is released (such as only the rosé Comtes de Champagne in 2003 and the Blanc de Blancs in 1998) in most vintages that are declared, both versions are released.

7.) I doubt Queen Victoria and Napoleon III time traveled to drink Perrier-Jouët’s Belle Epoque (Item #14)

With all the Champagne houses with histories of being run by widows, it’s kind of surprising that no one has ever done a special bottling for the world’s most famous widow.

Perrier-Jouët’s first release of the Belle Epoque was in 1964.

Cristaldi may have been trying to insinuate that those long-dead Champagne aficionados enjoyed the wines of Perrier-Jouët that were available during their time (which were FAR different in style than they are today). However, he’s dead wrong to say “Napoleon III, Queen Victoria and Princess Grace of Monaco were all fans of this gorgeous bubbly, which boasts classic white-floral notes (hence the label design), along with candied citrus and a creamy mouthfeel.”

I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt, though, on Princess Grace since she didn’t pass away till 1982.

Likewise….

8.) Marie Antoinette was dead more than 40 years before Piper-Heidsieck was founded (Item #15)

Kinda hard to be a brand ambassador when you don’t have your head. (Too soon?)

Again, I suspect this is just lazy research (and/or falling for marketing BS). But considering that the picture Cristaldi uses for his recommendation of Piper-Heidsieck (founded in 1834) is actually a Champagne from Charles Heidsieck (founded in 1851), the betting money is on general laziness.

A bottle of Piper-Heidsieck, in case Jonathan Cristaldi is curious.

Now for most people, I wouldn’t sweat them getting confused about the three different Champagne houses with “Heidsieck” in the name. While Champagne is nothing like Burgundy with similar names, there are some overlaps with the Heidsiecks being the most notable.

As I recounted in my recent review of the Heidsieck & Co Monopole Blue Top Champagne, the three houses (Heidsieck & Co. Monopole, Charles Heidsieck and Piper-Heidsieck) trace their origins to the original Heidsieck & Co. founded in 1785 by Florens-Louis Heidsieck.

But Piper-Heidsieck didn’t appear on the scene until 1834. That was when Florens-Louis’ nephew, Christian, broke away from the family firm to establish his own house. Even then, it wasn’t known as Piper-Heidsieck until 1837 when Christian’s widow married Henri-Guillaume Piper and changed the name of the estate.

Now, wait! Doesn’t the label on a bottle of Piper-Heidsieck say “founded in 1785”? That’s marketing flourish as the house (like the other two Heidsieck houses) can distantly trace their origins back to the original (but now defunct) Heidsieck & Co. But Christian Heidsieck and Henri-Guillaume Piper likely weren’t even born by the time Marie Antoinette lost her head in 1793–much less convincing the ill-fated queen to drink Piper-Heidsieck with her cake.

It’s not an issue for regular wine drinkers to fall for marketing slogans. But someone who is presenting himself as a wine educator (nay a Wine Prophet) should know better.

9.) Carol Duval-Leroy is not one of the few women to lead a Champagne house (Item #21)

Beyond ignoring the essential roles that women like Lily Bollinger, Louise Pommery, Marie-Louise Lanson de Nonancourt, Mathilde-Emile Laurent-Perrier and Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin (Veuve Clicquot) have played throughout the history of Champagne, it also discounts the many notable women working in Champagne today.

The De Venoge Princes Blanc de Noirs is made by a pretty awesome female chef de cave, Isabelle Tellier.

Maggie Henriquez, in particular, is one of the most influential people in Champagne in her role as CEO of Krug. Then you have Vitalie Taittinger of that notable Champagne house; Anne-Charlotte Amory, CEO of Piper-Heidsieck (and probable BFFs with Marie Antoinette’s ghost); Cecile Bonnefond, current president of Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin; Nathalie Vranken, manager of Vranken-Pommery; Floriane Eznak, cellar master at Jacquart; Isabelle Tellier, cellar master at Champagne Chanoine Frères and De Venoge, etc.

Is there room for more women in leadership in the Champagne industry? Of course, especially in winemaking. But let’s not belittle the awesome gains and contributions of women in the history (and present-day) of Champagne by sweeping them under the rug of “the few.”

Though what did I expect from a man who literally uses a woman as a “table” in his profile pic on his personal website?

Is there an end to the pain? God, I hope there is an end…

Though not as egregious as the glaring errors of mixing up Vintage vs. Non-vintage and touting long-dead brand ambassadors, I would be amiss not to mention one last thing that upset at least one of my Champagne-loving friends on Facebook.

At the end of his article Cristaldi throws out two (excellent) recommendations for a Californian sparkling wine from Schramsberg and a Franciacorta made in the traditional method in Italy. I appreciate that Cristaldi does point out that these two items are technically not Champagnes. However, it is hard not to miss the general laziness in how he leads off his article. He describes the list of wines to follow as “… some of the most iconic Champagnes out there, featuring an array of styles and price-points, so study up and become the Champagne know-it-all you’ve always wanted to be.” Again, a sin of imprecision and sloppiness.

To sum up this article, my dear Champagne-loving friend, Charles, had this to say about Jonathan Cristaldi’s article on Food & Wine.

The article is “riddled” errors. The author should be given an “ice bath” so that he can contemplate “disgorging” himself of the idea he is a master. At the very least someone should burst his “bubbles”. The article never should have made it to “press”

Now what?

I’m not going to claim to be a “Champagne Master” (though I’ll confess to being a Bubble Fiend) because frankly, I don’t think that title really exists. Even Tom Stevenson and Master of Wine Essi Avellan who literally wrote one of THE books on Champagnes and sparkling wine, probably wouldn’t consider themselves “Champagne Masters.”

To celebrate the Supreme Court decision in US v Windsor that legalized gay marriage nationwide, my wife and I threw a party in honor of the five justices that voted for equality.

People who put themselves in positions as wine educators or influencers owe it to their readers to provide valid information. Encouraging people to open bottles and try new things is terrific advice. Backing that advice up with falsehoods, embellishments, conflicting and confusing statements? Not so terrific.

No one knows everything and people make mistakes. It’s human nature. Hell, I’m sure I made at least one mistake in this post. But 9+ errors (2 of which are basic ‘Champagne 101’ stuff) is failing the readers of Food & Wine and everyone that those readers pass this faulty information along to.

Wine drinkers deserve better from our “prophets.”

Note: A follow up to this article can be found at Thought Bubbles – How to Geek Out About Champagne