Someone in South Carolina last month won $1.537 billion playing the Mega Millions lottery.

At the peak of the frenzy, retailers were selling 12,700 tickets a minute. It reached a point where so many people were playing, that experts estimated that all possible 302,575,350 combinations of numbers were likely claimed before the jackpot was finally won.

I didn’t get a ticket. Though I used to be quite a gambler in my younger days, now my risky activities involve more playing the Somm Game in Vegas and maybe putting a few dollars down on my St. Louis Cardinals, Blues and Mizzou Tigers.

Besides, I’m playing the lottery virtually every time I pull a bottle out from my cellar.

Sometimes I hit the jackpot and open up a wine at a point when it perfectly fits my palate. Other times it may be too young and “Meh-y”. Worst of all is when it is far past its peak time for giving me pleasure.

It’s always a gamble but, like a good gambler, I try to hedge my bets. With a little knowledge, you can too.

Hitting a Moving Target

The first thing we need to do is understand what is happening to a wine as it ages. While it looks simple on the surface, a bottle of wine is a living chemistry lab with an endless progression of reactions taking place between acids, phenols, flavor precursors, alcohol compounds and the like. It is estimated that there is anywhere from 800 to over a 1000 different chemical compounds in a typical bottle of wine.

All of these compounds will react differently to the unique environment of wine that is majority water (which we remember from high school chemistry is “the universal solvent”) as well as alcohol–which is also a pretty darn good solvent itself. Then you add in the potential reductive reactions (especially with screw caps) and slight oxidative reactions (especially with cork) and you have a whole cooking pot of change that is constantly happening to that bottle of wine sitting in your cellar.

Or a video game with that damn mocking dog

In many ways, it’s like a story that is constantly having a new chapter being written. That can be exciting as with each page you turn–each month or year you wait–you never quite know what’s going to happen next.

In other ways, it’s like a carnival game with the moving duck targets that you’re trying to hit to win a prize. Those can be fun or immensely frustrating.

Resources for more geeking

I don’t want to bog you down too much with the geeky science at this point. However, for those who do want to understand more about the chemical compounds in wine and how they change over time here are my three favorite wine science books on the topic.

Starting with the least technical (and easiest to read) to the uber-hardcore tome of wine science geekdom:

The Art and Science of Wine by James Halliday and Hugh Johnson. A tad outdated (2007) but this text covers the basics really well. The last section “In the Bottle” deals with the components of wine with a chapter specifically dedicated to what happens as a wine ages (“The Changes of Age”).

The Science of Wine: From Vine to Glass by Jamie Goode. There is a reason why Jamie is one of my favorite tools. He’s a brilliant writer who can distill complex science into more digestible nuggets for those of us who do not have a PhD. Like with Halliday and Johnson’s book, this will also spend a significant amount of time talking about the science behind viticulture and winemaking but in section 3, “Our Interaction With Wine”, he gets into how the changes happening to wine (as well as the environment of tasting) impact our perception of a wine’s components. This is very important because so much of knowing when to open a bottle of wine will depend on knowing when’s it good for you–something I’ll discuss more about below.

Wine Science: Principles and Applications by Ronald S. Jackson. This was one of my textbooks when I went to winemaking school so I won’t sugar coat how technical and dense it is. This is definitely not something you can read from cover to cover like with the first two books above. But if you really want to dive deep into the chemistry, there is no better resource out there. If you come from a non-scientific background, I do also recommend picking up some of the “For Dummies” refresher books like Chemistry Essentials and Organic Chemistry. Silly titles aside, those books certainly helped this Liberal Arts major understand and appreciate Jackson’s insights a whole lot more.

That said, I’m going to condense here some of what I’ve learned from those books above as well as my own experiences (and mistakes) in figuring out when to open a bottle.

What’s Happening to the Fruit?

When most people think of wine, they think of fruit. Therefore, it’s vitally important to understand what is happening to the fruit as a wine ages.

A good way to start is to think about cherries and the different flavors of its various forms.

A young wine can taste like freshly picked cherries.

With some age, the cherries flavors get richer and more integrated with the secondary notes of wine.

Gradually the fruit will fade till you’re left with the dried remnants.

Young wines (like say an Oregon Pinot noir) will have the vibrant taste of its primary fruit flavors–such a cherries picked right from the tree. Combined with the wine’s acidity, these cherry flavors with taste fresh and even juicy. But they can also be quite simple because the freshness of the fruit dominants. Think about eating ripe cherries. While delicious, there isn’t much else going on.

With a little age (like 5 to 10 years for that Oregon Pinot noir), the fruit gets deeper and richer in flavor. Think of more canned cherries that you would use to make a cherry pie. The wine will also have time to integrate more with the secondary flavors of the wine that originated during the fermentation and maturation. This often includes oak flavors like the “baking spices” that French oak impart–cinnamon, allspice, nutmeg, etc. These additional flavors add more layers of complexity. The fruit is still present. It’s just not as fresh and vibrant tasting as it once was.

Older wines with more age will see the fruit progressively fading. The flavors will start tasting like dried cherries as earthy and more savory tertiary flavors emerge. In the case of our Oregon Pinot, this could be forest floor, mushroom or even dried flowers and herbal notes. Eventually these tertiary flavors will completely overwhelm the faint remnants of dried cherries notes. When that happens will depend on the producer’s style, terroir and vintage characteristics. For me, I tend to notice the Oregon Pinots in my cellar go completely tertiary after 15 or so years.

Now…is that a good thing or a bad thing?

It depends. On you.

When Is Your Peak Drinking Window?

While nearly ever critic in the world will toss out “peak drinking windows” with their scores, that info is utterly useless if you’re not sure what you like.

Some people like lots of earthy, savory tertiary notes. That’s perfect and often the tail end of these critic’s windows will take those folks right through that sweet spot.

Other people might want more fruit and find those very aged wines to be disappointing. That’s also perfect because they may want to start opening up their bottles at the beginning of those windows or even a little before.

For me, I tend to like my wines just on the wane of the “pie filling fruit” stage when some of the tertiary notes are emerging but the wine still has a solid core of fruit. Going back to Oregon Pinots, I often find that between 7 to 12 years is my perfect window. However, in warm vintages, like 2009 and 2012, I’ve noticed an accelerated curve with many wines hitting my sweet spot starting at 5 years of age from vintage.

And sometimes it might not ever live up to James Suckling’s 96 point scores.

BTW, while we’re talking about critics. Keep in mind that when many professional critics give their scores out for wine, they are rating the wine based on how they think a wine is going to taste at its peak (i.e. during that window)–not necessarily how the wine is tasting right now. That’s the critic’s cover if that 96 point wine you’re buying based on the high score doesn’t live up to the hype. But even then, a critic’s “peak window” still might not match yours.

What’s Happening to the Structure?

Now fruit is just one component of the wine that’s impacted by aging. Often with bigger reds like Bordeaux varieties, a primary motivation for cellaring is to give the wine time to allow the structure of tannins and acid to soften.

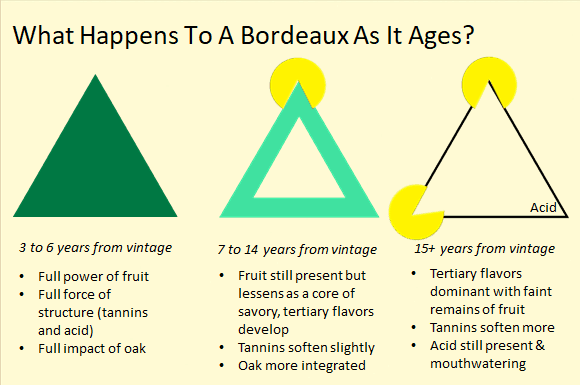

A good way to picture this is to think of the “bite” of firm tannins and acid as like a triangle with sharp edges. Below is a diagram that I recently used for a class I taught on Bordeaux wines based on my experiences of cellaring and drinking Bordeaux.

As the wine ages, some of the structure will soften but it won’t completely go away.

Also, as we discussed above, the core of fruit will still progressively fade.

The “softening” comes from the polymerization of the tannins as they link up with each to get bigger. These larger molecules tend to feel less aggressive on the palate. Think of it like adding tennis balls to round out the sharp edges of the corners of our triangle. The tannins are still there (as is the acid) but you feel their affects differently.

Eventually the wine will reach a point where it can’t get any softer. The triangle will never completely become a circle. That last bastion of a wine’s structure will not only be defended by the remaining soldiers of tannins but also by its acidity–which never goes away. While richer and deep fruit flavors (as well as complimentary flavors from esters) can help mask acidity during a wine’s prime, an aged wine will eventually start to taste more acidic and tart as that fruit fades.

However, that acidity will amplify the savoriness of tertiary flavors so, again, this all comes back to knowing what style of wine gives you the most pleasure. More fruity? More savory? Somewhere in the middle?

Learn From Other People’s Sacrifices

While critic’s drinking windows have some value, the very best resource on deciding when to open a wine are sites like Cellar Tracker.

Here you can track the progression of a wine through the impressions of other people who are sacrificing their bottles to Bacchus. Pay attention to the notes. Are they still talking about lots of fruit character? Big tannins? Or are the notes littered more with savory tertiary descriptors?

Now, yes, these folks will likely have different palates than you which is going to color their impressions. How they describe a wine yesterday might not be the same as how you would describe it today. But it is another data point that you can use to determine if it’s worth pulling the cork.

Lessons from Jancis Robinson

I have evolved my own theory that overall, vastly more wine is drunk too old than too young. — Jancis Robinson, November 26th, 2004

Jancis’ advice is even more valuable now than it was 14 years ago. In that time, we’ve seen quite a bit of change in the wine industry–including our ideas about cellar-ability. Part of it is the culture of impatience and desire for immediate gratification. Wineries know that they often don’t get a second chance at a first impression so a lot of effort takes place in the vineyard and the winery towards producing wines that are enjoyable soon after release.

We’re not even talking about whites and roses either.

Those efforts sometimes do involve a trade-off with a wine’s potential to age. The simple truth is, not many are being made to age anymore. In fact, some estimate that as much as 98% of the wine made today should be consumed within 3 to 5 years of the vintage date.

Now keep in mind, the vast majority of the world’s wines are made to be daily drinkers under $20 so that 3 to 5 year estimate is not that drastic. But even for more expensive bottles that you may be saving for a special occasion, I would encourage you to think about opening it up sooner rather than later.

For me, the math is simple.

If you open up a bottle too soon, there is still the potential that you could find another bottle to open later. Yes, you may have to do some hunting and pay a little bit of a premium but that potential still exist. Plus, you are still likely to get some pleasure from that bottle even if it wasn’t “quite ready”.

But….

If you open up a bottle too late, when the wine is far past the point of giving you pleasure, you’re screwed. All that time and all that investment went for nil.

There’s always a gamble when aging wine but, ultimately, it’s best to cash out when you’re ahead.

Going to need

Going to need