Note: All the wines reviewed here were samples provided on a press tour.

Back in my retail days, premium Napa Sauvignon blanc was always some of the hardest wines to sell. I’d have fantastic producers like Araujo, Bevan, Cakebread, Grgich Hills, Duckhorn, etc. sit on the shelf untouched. Even during the peak white wine season of summer, it took every bit of handselling savvy to get these bottles into baskets.

You’d think that good wine wouldn’t be that difficult to move, but Napa SB had two knocks against it.

1.) It’s a white Napa wine (usually) over $20 that’s not Chardonnay.

(Because, hey, why not get Chateau Montelena or Moone-Tsai Chard instead?)

2.) It’s a Sauvignon blanc over $20.

(Why spend more than Kim Crawford or Oyster Bay?)

Now I’m not saying that it’s impossible to sell a Napa Sauvignon blanc over $20.

Obviously, these bottles are selling somewhere (such as tasting rooms). But it’s a tough sell in many retail settings because of the way that most US stores are laid out.

Here you’ll often see varietal wines from New World regions like California, New Zealand, Chile and South Africa all grouped together. Napa Sauvignon blanc rarely seems like a compelling value when stocked among their more value-oriented peers. Even if a shop had a dedicated “California” or “American wine” section, these wines are still competing against sub-$20 options from Washington State, Sonoma, Monterey County, etc.

The few Napa bottles that manage to stay under that magical $20 mark–like St. Supery, Mondavi and Honig–tend to fare better. But even these wines regularly lose sales to other regions.

This is because, in the minds of many consumers, Napa Sauvignon blanc doesn’t have a distinctive style–only a distinctive price tag.

And while they’re more likely to swallow the Napa price for Chardonnay (and, of course, Cabernet Sauvignon), that halo effect rarely reaches the Sauvignon blanc aisle.

Instead, customers who are interested in spending top dollar for Sauvignon blanc are more likely to go over to the Old World aisles for Loire or White Bordeaux. Here, the premium pricing of Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé and Pessac-Leognan doesn’t drag each other down. More importantly, they promise a unique regional identity–which is key.

Back in the varietal section, those few customers reaching for the top shelf are more apt to grab Cloudy Bay. Or maybe one of the few other high-quality New Zealand Sauvignon blanc wines that make their way to the US. Even if you don’t know the producer, seeing the words “Marlborough” and “New Zealand” on the label promises something distinctive.

What is Napa Sauvignon blanc promising?

Something less green and herbaceous than New Zealand? Maybe. Though some producers have been experimenting with things like early harvest, heavier crop load and canopy shading to create more NZ-like flavors.

Something with a lavish texture and noticeable oak influence? Perhaps. These tend to be the more expensive and highly rated examples of Napa Sauvignon blanc. But, again, you have the question of why should a consumer who’s looking to spend top dollar for that style not go with a Chardonnay or white Bordeaux instead?

Which brings us back to the muddled middle that premium Napa Sauvignon blanc finds itself in. It’s not a value-priced wine. But it’s not as distinctive as other premium white wine categories.

Napa has to deliver something compelling–something interesting–to merit those lofty prices.

Of course, Napa wine is always going to be premium priced because of the high cost of land here.

They can’t rely just on the name “Napa” or even the quality in the bottle. Yes, having an outstanding wine helps sell in the tasting room where people can try it for themselves. But you don’t always have that privilege on the sales floor or restaurant table. Those premium bottles have to be hand-sold by an enthusiastic wine steward or sommelier who has already been wowed by the wine.

Though here’s the rub.

Every steward and sommelier is going to have dozens upon dozens of bottles that they’re passionate about. Everything from geeky varieties, obscure regions, small-lot productions to wineries with great stories–they all need handselling. Even hand-sold wines need to find ways to stand out from the pack.

In search of interesting Napa Sauvignon blanc.

During my trip to the Stags Leap District, I had many showstopping wines. And, yes, that included some absolutely delicious Napa Sauvignon blanc.

I noticed a pattern that many of the best examples prominently featured the Sauvignon Musqué clone. This caught my attention as growers in the Arroyo Seco region of Monterey County are also using this clone to make some thoroughly intriguing wines.

A few of my favorites were:

2018 Taylor Family ($40) made from 100% Musqué clone from Yountville.

2017 JK Ilsley ($35) also from Yountville and majority Musqué.

2017 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellar Rancho Chimiles ($40) made from 86% Musqué. This was way more aromatic and textural than SLWC’s regular Aveta Sauvignon blanc ($26) that is only 8% Musqué.

But as delicious as those wines were, it’s hard to say that they were compelling enough to merit a $20+ price tag–especially compared to the similarly delicious Sauvignon Musqué from areas like Arroyo Seco that cost far less. Picturing these bottles sitting on the same retail shelf, it’s not hard to see the higher-priced Napa bottles gathering dust.

However, there was one Napa Sauvignon blanc-based wine that more than stood out as being worth every penny.

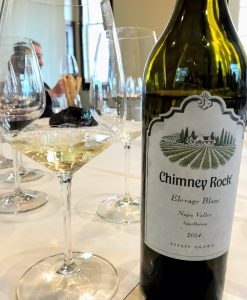

The Chimney Rock Elevage Blanc ($50).

I was already familiar with Elizabeth Vianna’s outstanding Cabernet Sauvignon. Nestled in the southern end of the Stags Leap District, neighboring Clos du Val and one of Shafer’s vineyards, this is obviously prime red wine territory. But instead of offering the typical Carneros Chardonnay that is omnipresent in Napa, Chimney Rock’s flagship white is a fruit-forward but elegant white Bordeaux style blend–with a twist.

Bordeaux-style wine made by a Brazilian winemaker at a Cape Dutch-inspired winery in the heart of Napa. There’s a lot going on at Chimney Rock and it’s all delicious.

Vianna has never been a fan of Semillon from Napa. Compared to Bordeaux, Semillon gets too lush and fat here. Now winemakers could do a juggling act with early harvests (like they do in the Hunter Valley) to retain acidity. But while that may work for a low alcohol varietal wine requiring long term aging, it’s not necessarily the ideal match for adding depth to Napa Sauvignon blanc.

Instead, Vianna and her predecessor, Doug Fletcher, fell in love with the “secret ingredient” hidden in many of the best white Bordeaux–Sauvignon gris.

Chateau Palmer in Margaux; Haut Brion, Smith Haut Lafitte and Pape Clement in Pessac-Leognan; Valandraud, Fombrauge and Monbousquet in St. Emilion. Depending on the vintage, you’ll often find anywhere from 5% up to 50% (2018 Blanc de Valandraud) of Sauvignon gris in these highly-acclaimed wines.

So what the heck is Sauvignon gris?

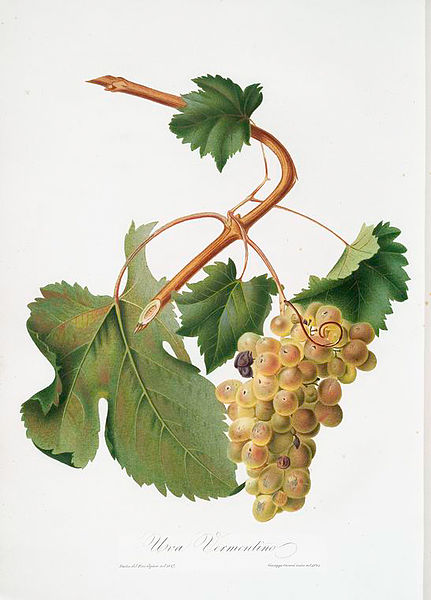

Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding and José Vouillamoz’s Wine Grapes notes that Sauvignon gris is a color mutation of Sauvignon blanc. Similar to the Pinot gris mutation of Pinot, it’s not known precisely where Sauvignon gris first emerged.

One possibility is the Loire, where the grape is known as Fié. Ridiculously low yielding, the vine was almost wholly lost to phylloxera as producers replanted with other varieties. It’s only recently, with the rediscovery of abandoned old vine vineyards such as Jacky Preys’ site in Mareuil-sur-Cher, that Sauvignon gris is getting another look.

Compared to Sauvignon blanc, Sauvignon gris tends to have slightly thicker skins often with a pink hue. It produces wines of medium-plus to high acidity with pronounced, concentrated flavors of melon, mango, stone and citrus fruit as well as a robust floral component. In the cooler climates of the Loire, it can add some subtle herbaceous notes though it rarely gets as green as Sauvignon blanc.

In addition to the Loire and California, producers in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Moldova and New Zealand are also experimenting with Sauvignon gris.

A tasting of three Chimney Rock Elevage Blanc

Tasting the Elevage Blanc and other Chimney Rock wines with Elizabeth Vianna and Kenneth Friedenreich, author of Oregon Wine Country Stories.

The winemaking of Elevage Blanc is very Bordeaux-like with a mixture of barrel fermentation and stainless steel using several yeast stains for complexity. The barrel component (usually around 1/3 new French and 1/3 neutral) sees frequent bâttonage beginning with 3-4 times a week and then gradually decreasing. The wine often goes through malolactic fermentation for stability. Depending on the vintage, around 3000 cases a year are made.

2008 Elevage Blanc – 70% Sauvignon blanc, 30% Sauvignon gris

Medium-plus intensity nose of tropical fruit with a savory, smokey component. Proscuitto wrapped melon-balls comes to mind. Along with the melon is some noticeable spiced pear.

On the palate, the pear and oak spices (nutmeg, clove) come through with a little cardamon. The slightly salty, savory, smokey notes are there as well but less pronounced than they were on the nose. The full-bodied mouthfeel is well balanced with medium-plus acidity–giving a lot of life to this wine. But the moderate finish lingering on the spice shows that its time is nearing the end. Still quite impressive for a 10+-year-old white wine.

2014 Elevage Blanc – 54% Sauvignon gris, 46% Sauvignon blanc

High-intensity nose. Intense fresh and grilled peaches. Less noticeable oak than the 2008 with the smokiness being more flinty. This one was also the most floral of the three with a mixture of elderflower and white lilies. Very mouthwatering bouquet.

On the palate, the peaches carry through joined by apples that also have a grilled component. Again, the oak is far less noticeable with maybe some subtle vanilla creaminess to go with the full-bodied richness. However, the high acidity keeps this wine well in check. The mouthwatering grilled peaches continue throughout the long finish. The highest proportion of Sauvignon gris and one of the best wines I had on the entire trip.

2016 Elevage Blanc – 79% Sauvignon blanc, 21% Sauvignon gris

Medium-plus intensity nose–apple and citrus-driven (star fruit, lemon). It’s the only one of three without a smokey, savory component. However, the oak is noticeable with pastry dough and clove spice. With air, tropical mango emerges as well as very ripe apricot.

On the palate, the toasty pastry and ripe tree fruit (apple & apricot) carry through. While not as heavy and oaky as a Chard, this one definitely feels the weightiest with the pastry tart element. Medium-plus acidity helps keep the full-bodied wine balanced. It also highlights more of the citrus flavors from the nose, bringing some pomelo to the party. Those more defined fruits offset the oak flavors, letting the citrus dominant the medium-plus length finish.

Takeaways

Definitely was one of my top wines of 2019. Such a stellar white that still has several years to go.

While 2014 was my clear favorite, each of these Elevage Blancs was well worth a premium $50 price. They had complexity with each vintage showing its own distinct and unique personality.

It’s clear that Sauvignon gris, itself, adds interesting elements when blended with Sauvignon blanc that you don’t always get with Semillon or Muscadelle in white Bordeaux. Most notable for me was how Sauvignon gris seems to deal with oak, steering the wine towards more savory flavors as opposed to just “oaky” notes.

In contrast, I feel like Semillon and Sauvignon blanc tend to absorb oak flavors like a sponge–making the wine feel more Chardonnay like. It was notable that as the quantity of SG decreased, the oak in the Elevage Blanc became more noticeable.

Blend vs. Varietal

Only the 2016 vintage of Elevage Blanc could be labeled as a varietal Sauvignon blanc. But maybe ditching the varietal designation is the answer to avoiding that muddled middle which plagues these Napa white wines? While a New World “white blend” aisle probably doesn’t get as much traffic as the Sauvignon blanc section, it doesn’t come with the baggage either.

A premium Napa white blend isn’t competing with the value-driven options from New Zealand, Chile and elsewhere. Instead, it can pull more of the “halo effect” of the Napa name as it stands out from various white blends from Lodi, Paso Robles, Sonoma, Washington State, etc.

There is still the question of regional identity, but not many regions have staked a claim to Sauvignon gris. No matter which style you go with–crisp, stainless or lavish, oak-driven–Sauvignon gris adds its own “twist” to the wine. This is something that Napa can sink its teeth into, crafting a distinct regional style of Sauvignon blanc/Sauvignon gris blends.

Though, they better hurry before someone else beats them to the punch.

Today is

Today is

Going to need

Going to need