Note: Unless otherwise stated, all the wines reviewed here were tried as samples during the 2019 Wine Media Conference in the Hunter Valley and Mudgee region.

The wine world has a wicked way of promoting FOMO–a fear of missing out.

From the luxury end, there are cult wines and trophy bottles. In years past, score hounds would scavenge the shelves looking for highly-rated gems before they sold out.

Now for wine geeks and wanderlust Millennials, the entire world of wine is a temptress. But what we fear missing out on is not what the pack is gobbling up. Instead, our minds quiver at the thought of missing out on what’s new and exciting by settling for what’s old and boring.

Why feel content with the same ole Cab and Chardonnay when you could have Touriga Nacional and Grenache blanc?

Yeah, Champagne is charming. Prosecco is perfect for patio sipping. But that’s what everyone else is drinking. It’s what you can find in every wine shop. You can’t have FOMO if there is nothing to be missed.

And that’s the dirty little secret of the human psyche.

Despite the real repercussions when we let FOMO reach anxiety levels, we still crave it. We still crave the thrill of the hunt. But how much thrill is there in shooting ducks in a basket?

No, what we crave are the unicorns out in the wild.

In the world of sparkling wine, finding premium Aussie bubbles is a tough unicorn to bag. Unless, of course, you’re one of the 25 million people who call Australia home.

Now yes, we’ll get some sparkling Shiraz exported.

Actually Australia is home to many unicorns.

If only I could’ve found a way to keep these frozen for the plane ride home.

Though the ones that make their way to the US tend to be mass-produced and underwhelming. Of course, there is the ubiquitous YellowTail, which has several sparklers in their line up. However, that’s basically the “Fosters of Australian wine”–a well-known ambassador but not really a benchmark.

Occasionally, some internet sleuthing can find a merchant offering mid-size producers like Jansz from Tasmania. (Though, ugh, their website!)

But only around a fifth of Australia’s sparkling wine production gets exported. That means you need to go down under to even get a hint of what the rest of the world is missing out on. Luckily, I got such a chance this past October during the Wine Media Conference.

There, in both the Hunter Valley and neighboring Mudgee, I was able to try several sparkling wines that I could never find in the States. But I barely scratched the surface. Even spending extra time in Sydney, I found that the highly regarded Tasmanian sparklers were surprisingly difficult to find.

I’ll share my thoughts on many of the sparklers I tasted below. But first a little geeking about Australian sparkling wine.

Australia isn’t an “emerging” sparkling wine producer.

Bubbles were produced on the island of Tasmania nearly 2 decades before Nicholas Longworth crafted the first American sparkling wine in 1842.

As Tom Stevenson and Essi Avellan note in the Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine (one of the five essential books on sparkling wine), an English immigrant, Mr. Brighton, produced Australia’s first sparkling wine in Tasmania back in 1826.

I’d imagine it was quite the scandal having a non-French sparkler served to the French emperor.

Up in the Hunter Valley, James King began producing sparkling wine around 1843. King’s wines would receive great international acclaim–doing particularly well at the 1855 Paris Exposition. Yes, that 1855 Paris Exposition. At the end of the event, King’s sparkling Australian wine was selected as one of only two wines that were served to Napoleon III at the closing banquet.

It’s hard to know exactly what these first Aussie sparklers were. King, in particular, was noted for the quality of his Shepherd’s Riesling (Semillon). However, he also had Pinot noir in his vineyard as well.

These early Australian sparklers were made using the traditional method of Champagne.

The 20th century saw more innovation in sparkling wine techniques with producers experimenting with a “twist” on the Champagne method known as the Transfer Method or transvasage. (We’ll geek out more about that down below) The exact date and who was the first to pioneer this technique in Australia is not known though Minchinbury helped popularize its use.

In 1939, Frederick Thomson started using carbonation (or the “soda method”) to make his Claretta sparkling fizz. We should note that while many cheap sparkling wines (including some so-called “California Champagnes”) are made with added carbonation, in Australia these wines can’t be labeled as “sparkling wines.” Only wines that get their effervescence through fermentation (either in a bottle or tank) can use the term.

Speaking of tanks, adoption of the Charmat method took hold in the late 1950s–beginning with Orlando’s Barossa Pearl Fizz. Today, the tank method is gaining in prominence–especially with the strong sparkling Moscato and “Prosecco” market in Australia. (More on both of those a little later too.)

The 1980s saw a spark of French interest in Australia.

Much like in California, the big Champagne houses took an interest in Australia’s growing sparkling wine industry. In 1985, both Roederer and Moët & Chandon invested in new estates.

Roederer help found Heemskerk as a joint-venture in Pipers Brook, Tasmania. But eventually Roederer moved on from the project–selling back their interest in the estate in 1994.

Throughout Australia, sparkling wine accounts for around 6% of production. In Tasmania, that number jumps up to 30%.

Moët’s Domaine Chandon at Green Point in the Yarra Valley of Victoria, though, saw immediate success thanks to the work of the legendary Tony Jordan–who sadly passed away earlier this year.

Like Roederer, LVMH also looked to Tasmania as a potential spot for sparkling wine production. However, they wanted a location more prime for tourism and cellar door sales.

Bollinger was also briefly a player in Australia’s sparkling wine scene through their partnership with Brian Croser in Petaluma. However, the hostile takeover of that brand by the Lion Nathan corporation in 2001 seemed to have ended Bollinger’s involvement.

Today, except for Domaine Chandon (and Pernod Ricard’s Jacob’s Creek), most all of the Australian sparkling wine industry is wholly domestic. This makes me wonder if this is why Aussie sparklers are so hard to find outside of Australia?

Even the most prominent players like Treasury Wine Estates (Wolf Blass, Penfolds, Seppelt, Heemskirk, Yellowglen) and Accolade Wine (Banrock Station, Arras, Bay of Fires, Hardy’s, Croser, Yarra Burn) have their origins as Australian conglomerates before they gained an international presence.

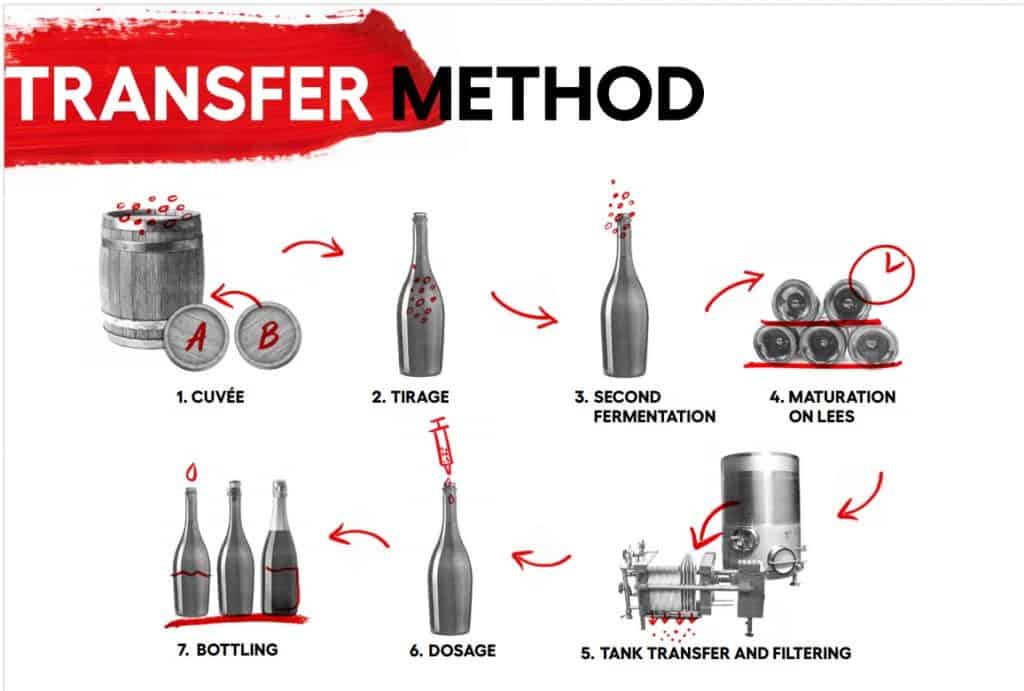

The Transfer Method

Diagram from Wine Australia’s “Australian Wine Discovered” presentation.

Understanding this is a big part of understanding Australian sparkling wine. Like the traditional method, fermentation happens in the bottle. However, it’s not happening in the bottle that you’re taking home. Instead, after secondary fermentation and aging, the wine is emptied into a pressurized tank at around 0°C where the lees are filtered out. Then the sparkler is bottled anew with its dosage.

The Champenois themselves use transvasage for 187ml airline splits and half bottles as well as large format Champagnes starting with double magnum (3L Jeroboam) in size. This is because these odd formats would be difficult to riddle without excessive breakage.

The Australians were keen to adopt the labor and cost-saving benefits of the transfer method and it’s the most widely used technique. It allows wineries to increase efficiency without sacrificing the quality character of autolysis. Ed Carr of Accolade Wines noted in Christie’s that the difference is as much as $30-40 AUD per case compared to traditional riddling. Plus, winemakers can do one last “tweaking” (such as SO2 and acidity adjustments) before final bottling.

However, many boutique producers stick to using the traditional (instead of transfer) method. These bottles are labeled stating “Methode champenoise,” “Methode traditionnelle” or simply “Fermented in this bottle.”

The sparklers that are made using the transfer method are more likely to state that they are “Bottled Fermented” or “Fermented in the bottle.”

Australian Moscato & “Prosecco”

As elsewhere in the world, Australia has had its own “Moscato Boom.”

Now usually Moscato is associated with the Moscato bianco grape of Asti (Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains). However, in Australia, the term is used to refer to the whole Muscat family when the wine is made in a light, sweet style with low alcohol. So a bottle of sparkling Australian Moscato can be made from Moscato bianco, Muscat of Alexandria, Orange Muscat, Moscato Giallo or a blend of multiple Muscats.

The King Valley in north-east Victoria has a strong Italian heritage. The Glera/Prosecco grape thrives in the cooler southern end of the valley with vineyards planted at higher altitudes.

Australian Prosecco is also apparently a big deal–though I didn’t personally encounter any bottles on my trip. The first Australian Prosecco was made by Otto Dal Zotto in King Valley (or “Victoria’s little Italy”) in 2004. The success of that wine and others caught the attention and ire of producers in the Veneto.

This led Italian authorities to take some dramatic steps in 2009. First, they petitioned the EU to change the grape’s name from Prosecco to Glera. Then they expanded the DOC to the province of Trieste, in Friuli Venezia Giulia, where there is a village named Prosecco. This gave them the justification to claim the entire region as a protected geographical area.

Obviously Australian wine producers balked at this with the conflict between the two parties still ongoing. But while Australian Prosecco can be sold domestically, none of these wines can be exported into the EU.

A few of the Australian Sparklers I’ve enjoyed this year.

Amanda and Janet de Beaurepaire at their family estate. Amanda’s parents, Janet and Richard, started planting their 53 hectares of vineyards in 1998.

De Beaurepaire 2018 Blanchefleur Blanc de Blancs – $45 AUD (Purchased additional bottles at winery)

I’ve got a future article planned about the intriguing story of the De Beaurepaire family and the genuinely unique terroir they’ve found in Rylstone, southeast of Mudgee. The family’s name and ancestors come from the Burgundian village of Beaurepaire-en-Bresse in the Côte Chalonnaise. So it’s no surprise that their wines have a French flair to them.

It’s also no surprise that their 2018 Blanchefleur was quite Champagne-like. Indeed, it was the best sparkling wine I had on the trip. A 100% Chardonnay with 15 months on the lees, this wine had incredible minerality. Coupled with the vibrant, pure fruit, it screamed of being something from the Cote de Blancs. I’m not kidding when I say that this bottle would stack up well to a quality NV from a grower-producer like Franck Bonville, Pierre Peters, De Sousa or Pertois-Moriset.

Peter Drayton 2018 Wildstreak sparkling Semillon-Chardonnay – $30 AUD

I had this at an Around the Hermitage dinner that featured many gorgeous wines. But the folks at the Around Hermitage Association started things right with this 80% Semillon/20% Chardonnay blend that spent 18 months on the lees. Hard to say if this was transfer method of not. However, the toasty autolysis notes were quite evident with biscuit and honeycomb. Very Chenin like. In a blind tasting, I’d probably confuse it with good quality sparkling Vouvray from a producer like Francois Pinon or Huet.

BTW, the Around Hermitage folks made a fun short video about the dinner (3:20) which features an interview with me.

Logan 2016 Vintage ‘M’ Cuvee – ($40 AUD)

With a blend of 63% Chardonnay, 19% Pinot noir and 18% Pinot Meunier, this is another bottle that is following the traditional method and recipe. Sourced from the cool-climate Orange region of NSW, which uses altitude (930m above sea level) to temper the heat, this wine spent almost two years aging on the lees. Lots of toasted brioche with racy citrus notes. It feels like it has a higher Brut dosage in the 10-11 g/l range. But it’s well balanced with ample acidity to keep it fresh.

Hollydene Estate 2008 Juul Blanc de Blancs – $69 AUD

Hollydene Estate Winery in Jerrys Plains is about an hour northwest of the heart of the Hunter Valley in Pokolbin.

Made in the traditional method, this wine is 100% Chardonnay sourced from the cool maritime climate of the Mornington Peninsula in Victoria. It spent over 60 months aging on the lees and, whoa nelly, you can tell. Hugely autolytic with yeasty, doughy notes to go with the lemon custard creaminess of the fruit.

Peterson House 2007 Sparkling Semillon – ($60 AUD)

If you love sparkling wine, make sure you book a trip to Peterson House. Each year they release more than 30 different sparklers. Beyond just the traditional varieties, they push the envelope in creating exciting bubbles. You’ll find sparklers made from Verdelho, Pinot gris and Sauvignon blanc as well as Chambourcin, Petit Verdot and Malbec.

I’m generally not a fan of overly tertiary sparklers. But this wine made a big impression on me during the conference.

Wow! A vintage sparkling traditional method Semillon that spent 11 years on lees. 11 years!

Apple and lemon strudel with brioche. Crazy complex for something that is only $60 AUD ($45 USD). A true Brut at 3 g/l. #WMC19 @PetersonHouse1 pic.twitter.com/Nufrv7ly6M

— Amber @ SpitBucket.net (@SpitbucketBlog) October 12, 2019

Robert Stein NV Sparkling Chardonnay and Pinot noir – $25 AUD

I raved about the Robert Stein Rieslings in my recent post, Send Roger Morris to Mudgee. But there are so many good reasons to put this winery (and the Pipeclay Pumphouse restaurant) on a “Must Visit Bucket List”. The entire line up is stocked with winners–including this Charmat method sparkler.

At first taste, I had this pegged for transfer method. It wasn’t as aggressively bubbly and frothy as many tank method sparklers can be. However, the considerable apple blossom aromatics should have tipped me off. If this ever made its way to the US for less than $30, I’d recommend buying this by the case.

Gilbert 2019 Pet Nat Rose – $25 AUD (Purchased additional bottles at winery)

Gilbert’s Sangio Pet-Nat was just bloody fantastic. I wish I brought more than one bottle home.

It’s always trippy to have a wine from the same year (2019)–especially a sparkler. Gilbert harvests the Sangiovese in February and bottles before the first fermentation is completed each year. Released in July, this wine was surprisingly dry and is teetering on the Brut line with 12.5 g/l residual sugar. Very clean with no funky flavors, this wine had a beautiful purity of fruit–cherry, strawberries, watermelon and even blood orange.

Domaine Chandon 2013 Vintage Brut (purchased at a restaurant) – Around $30 AUD retail.

The Christie’s Encyclopedia notes that Domaine Chandon shot out of the gate partly because of the lessons that Tony Jordan learned at Napa’s Domaine Chandon. In particular, Jordan was well aware of the challenges of dealing with grapes from warm climates. In Australia, Domaine Chandon casts an extensive net by sourcing from cool-climate vineyards in both Victoria and Tasmania. They have vineyards not only in the Yarra Valley but also in the King Valley, Macedon Ranges, Whitlands Plateau and Strathbogie Ranges as well as the Coal River Valley region in Tasmania.

For the fruit that comes from Tasmania, Domaine Chandon follows the tact used by many Australian sparkling wine producers. They press the fruit at local press houses in Tasmania before transporting the must in refrigerated containers to the mainland. This helps maintain freshness and ward off spoilage organisms.

The 2013 vintage Brut is 47% Chardonnay, 50% Pinot noir and 3% Pinot Meunier. As in Champagne, Domaine Chandon ages their vintage sparklers at least 36 months on the lees. Fully fermented in the same bottle, it tastes very similar to other Moët & Chandon sparklers with rich, creamy mouthfeel holding up the ripe apple and citrus notes. An enjoyable bottle priced in line with its peers.

Bleasdale Sparkling Shiraz (tasted in London at the WSET School) – Around 15 euros

I’ll admit that the color of sparkling Shiraz is always very striking.

Admittedly I’m still on the search for a genuinely impressive sparkling Shiraz. But this Bleasdale came close. Like the Paringa I’ve reviewed previously, it’s sweeter than my ideal though I get the winemaking reasons behind that.

Sparkling red wines are notoriously tricky to pull off because you have to balance the tannins. This is why many of these wines often have more than 20 g/l sugar.

Most sparkling reds come from the same regions as premium Australian still reds. Think places like the Barossa, McLaren Vale or the Langhorne Creek (Bleasdale). Interestingly, producers will harvest these grapes at the same time as those for still reds wine. Instead of harvesting early to retain acidity, producers want the extended hang time for riper tannins.

However, these sparklers sorely need acidity to balance both the intense fruit and sweetness. While secondary fermentation does add carbonic acid, I suspect that these wines are routinely acidified.

Still, this Bleasdale had enough balance of acid to go with the dark plum and delicate oak spice. That got me wondering how well this would pair with BBQ pulled pork.

Or, if I’m brave, maybe I’d pair some of these Aussie sparkling unicorns with steak de cheval.