Over the next several months I will be working on a research project about the stories and wines of the Stags Leap District. In 2019, this Napa Valley region will be celebrating the 30th anniversary of its establishment as an American Viticultural Area. So in between my regular features and reviews, you can expect a fair sprinkling of Stags Leap geekiness.

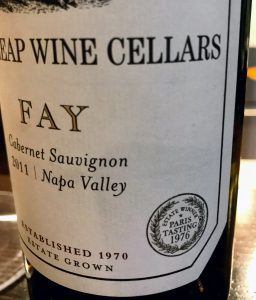

My review of the 2011 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars Fay Vineyard is down below.

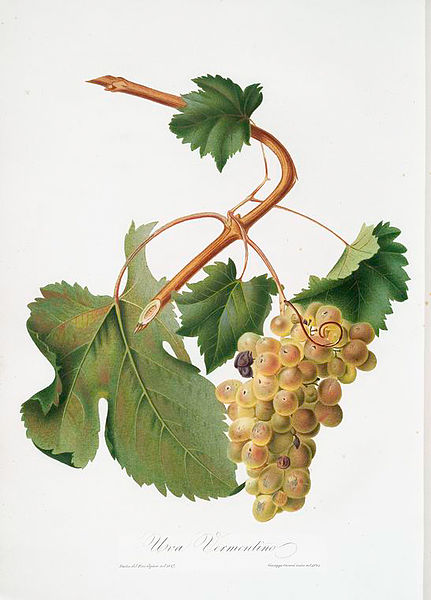

Today the wines of the Stags Leap District are part of the robe that drapes Napa Valley in prestige and renown. However, originally that wasn’t the case. As the sleepy valley shook off the dust from decades of Prohibition and ambivalence, this little pocket in the shadow of the Vacas was dismissed as too cold for Cabernet Sauvignon.

While ambitions were growing up-valley in places like Oakville and Rutherford, the Stags Leap District was known for cattle and prunes. It took a single wine, from three-year-old vines, to shake the world into casting its gaze on this three-mile long “valley within a valley.”

But before anyone had reason to give the Stags Leap District a look, Nathan Fay took a leap.

The Origins of Fay Vineyard

A native of Visalia in the San Joaquin Valley, Nathan Fay moved to Napa in 1951. He purchased 205 acres in 1953 that was once part of the Parker homestead dating back to the 1880s. The land included several acres of prune trees that were a popular planting in the valley.

But following World War II, the fortunes of the Napa prune industry was on the decline. As William Heintz noted in his work California’s Napa Valley: One Hundred Sixty Years of Wine Making, Napa prunes were facing stiff competition from large-scale producers in the Sacramento Valley. Not only was the production bigger, but so were the prunes. Their size, Heintz shared, made them look more appealing in supermarket cellophane bags than their less plump Napa cousins.

The Stags Leap Palisades frame the east side of its namesake district and profoundly influences the terroir.

Then Napa’s most lucrative export market for prunes, the United Kingdom, shriveled as cheaper options from Hungary became available. Faced with these prospects, Fay sought the advice of the University of California-Davis. They encouraged him to switch to viticulture.

But the experts at Davis cautioned Fay against planting “warm weather grapes” like Cabernet Sauvignon, noting the chilly maritime winds that funneled up through the Stags Leap District in the late afternoon.

They didn’t take into consideration the influence of the Stags Leap Palisades. Fay had noticed, how during the heat of the day, these hills of volcanic rock would absorb the sun’s warmth. In the evening, after the wind had passed, they would radiate it back to the land. Fay also knew that the famous region of Bordeaux, well known for Cabernet, had its own maritime influences to deal with.

A Hunch and Some Hope

Conversations with the Mondavi brothers of Charles Krug gave Nathan Fay a hunch that there was a market for Cabernet Sauvignon grapes. In 1961, he took the plunge, planting the first sizable acreage of Cabernet south of Oakville. When those 15 acres of vines came of age, the Mondavis were his first customers with Joe Heitz of Heitz Cellars soon following. Then came George Vierra of Vichon, Frances Mahoney of Carneros Creek and others looking to buy Fay grapes.

By 1967, Fay was expanding his plantings, moving from the deep alluvial soils on the west side of his property to the shallow volcanic soils closer to the Palisades. With the help of his friend, Father Tom Turnbull, Fay planted 30 additional acres of Cabernet Sauvignon.

The Wine That Started It All?

Warren Winiarski in 2015, many years after his fateful meeting with Nathan Fay.

While the 1973 Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars gets the glory of winning the Judgement of Paris, in many ways that bottle was the moon reflecting the light of a 1968 Cabernet Sauvignon made by Nathan Fay. It was the pull of this wine, made from Fay’s vines, that changed the gravitation of Warren Winiarski’s career–and perhaps that of the entire Napa Valley.

George Taber describes Winiarski’s 1969 visit with Fay in his book Judgment of Paris: California vs. France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting That Revolutionized Wine. Winiarski had finished the first two vintages as the inaugural winemaker of Robert Mondavi Winery and was looking to start his own operation.

He had planted a few acres up on Howell Mountain but found that his Cabernet Sauvignon buds were not taking to their grafts due to insufficient water in the soils. Winiarski was intrigued by irrigation techniques that Nathan Fay was experimenting with on his property. So he went down the Silverado Trail to pay him a visit.

While the two gentlemen discussed farming, Fay took Winiarski to a small building across from his house along Chase Creek where he kept barrels of his homemade wine. While Fay sold most of his grapes, he saved enough to make a few cases each year.

Tasting this young and roughly made wine, Winiarski found the aromatics and texture to be unlike anything else he had tried in Napa. The experience impacted him so dearly that when the land next to Fay’s vineyard, the 50 acre Heid Ranch, went up for sale the following year, Winiarski sold his Howell Mountain property and purchased the site.

Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars and the Fay Vineyard

Entrance towards the winery and tasting room of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars.

The wine that beat some of the best of Bordeaux was not made from Fay grapes. The fruit for that 1973 bottling came from the young vines next door where the two sites shared the same deep alluvial soils. Most of the Cabernet buds Winiarski used for the new vineyard were from Fay’s vines with a few from Martha’s Vineyard in Oakville as well.

In 1986, Nathan Fay was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Wanting to scale back, he negotiated a sale for most of his vineyard to Winiarski. By 1990, Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars was producing a vineyard-designated Fay Vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon. Fay passed away in 2001 with Winiarski acquiring the rest of this fabled vineyard from Fay’s heirs in 2002.

In 2007, Winiarski sold Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars and its vineyards to a partnership of Ste. Michelle Wine Estates and the Antinori family. He agreed to stay as a consultant through the 2010 vintage and winemaker Nicki Pruss remained through 2013. That year, Ste. Michelle Wine Estates brought Marcus Notaro down from Col Solare in Washington State to take over the winemaking.

Since 2006, Kirk Grace, the son of legendary Napa cult wine producers Dick and Ann Grace of Grace Family Vineyards, has been the vineyard manager. During his tenure, Fay and Stag’s Leap Vineyard have converted to sustainable viticulture, earning Napa Green certification in 2010.

A Stable of Wines

Since Winiarski’s retirement, bottles of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars wines no longer feature his signature above the establishment date.

They do, however, note his 1976 triumph in Paris.

The Fay Vineyard is one of four Cabernet Sauvignon bottlings that Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars produces. Kelli White notes in Napa Valley Then & Now that, along with Cask 23 and S.L.V., Fay is always 100% Cabernet Sauvignon and estate-grown fruit. The entry-level Artemis is made from mostly purchased fruit and will often include Merlot and some Malbec.

Both Fay and S.L.V. will see around 20 months aging in 100% new French oak. The Cask 23, which is a blend from the two vineyards, will have 21 months in 90% new French oak. The Artemis is usually aged for 18 months in a mixture of American and French oak barrels with only about a quarter new. While the winery typically makes these wines every year, the quality of the 2011 vintage led them not to release a Cask 23.

Review of the 2011 Fay Cabernet Sauvignon

Medium intensity. Noticeable pyrazines right off the bat. Green bell pepper that overwhelmingly dominates the bouquet. Tossing it in the decanter for splash aeration allows some tobacco spice to come out, but it’s green uncured tobacco. Fighting through the greenness finally brings up a mix of red cherry, currant and a faint floral note that isn’t very defined.

On the palate, the green bell pepper, unfortunately, carries through but the medium-plus acidity adds more lift to the red fruit flavors. It also highlights the oak spice of cinnamon and allspice. Medium-plus tannins are soft with the velvety texture you associate with a Stags Leap District wine. They balance well with the medium-bodied fruit. Moderate finish still lingers on the green with the uncured tobacco hitting the final note.

The Verdict

Folks that are less sensitive to pyrazines might not mind this 2011 Fay. But for me, getting past the green bell pepper was a tall order

It would be incredibly unfair to harshly judge the terroir of the Fay Vineyard and winemaking of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars based on a 2011 wine. While there were some gems from that troublesome vintage (Chappellet, Paradigm, Barnett Vineyards, Corison, Moone-Tsai and Frank Family being a few that I’ve enjoyed), you can’t sugarcoat the challenges of 2011. The cold, wet vintage made ripening a struggle. Come harvest time many wineries had to be aggressive in the vineyard and sorting table to avoid botrytis.

While I applaud Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars for realizing that this vintage didn’t merit producing their $250-300 Cask 23, it’s hard to say that it warranted making a $100-130 Fay Vineyard either. I’m not a fan of dismissing vintages wholesale but 2011 is a year that you have to be careful with. Great vineyards and winery reputation (or glowing wine reviews) won’t spare you from striking out on expensive bottles.

If you’re going to seek out a Fay Vineyard Cabernet, there is a charm in finding some of the Warren Winiarski vintages from 2009 and earlier. But I would also be optimistic about the more recent releases from the new winemaking team as well. While they might be different in style compared to the Winiarski wines, better quality vintages will be far more likely to deliver pleasure that merits their prices.