Champagne is the benchmark for all sparkling wine. Any wine student studying for advance certifications needs to be able to explain what makes Champagne unique. They also should be familiar with important producers–both big houses and influential growers.

While there are certainly online resources available, few things top a great reference book that can be highlighted and annotated to your heart’s content.

One of the best tips for wine students (especially on a budget) is to check out the Used Book offerings on Amazon. Often you can find great deals on wine books that are just gently used. This lets you save your extra spending money for more wine to taste.

Since the prices of used books change depending on availability, I’m listing the current best price at time of writing. However, it is often a good idea to bookmark the page of a book that you’re interested in and check periodically to see if a better price becomes available.

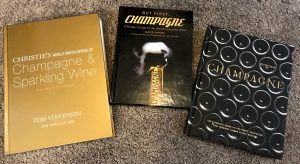

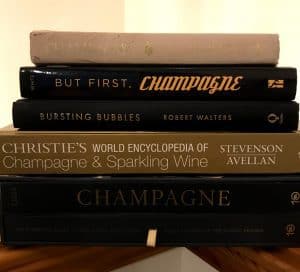

Here are the five most essential books on Champagne that every wine student should have.

Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine by Tom Stevenson & Master of Wine Essi Avellan (Used starting at $29.97)

The Christie’s encyclopedia is ground zero for understanding the basics about Champagne (production methods, styles, grape varieties, etc). But, even better, it is a launching pad for understanding the world of sparkling wine at large and seeing how Champagne fits in that framework.

While Champagne will always be a big focus of most wine exams, as my friend Noelle Harman of Outwines discovered in her prep work for Unit 5 of the WSET Diploma, you do need to have a breadth of knowledge of other sparklers.

In her recent exam, not only was she blind tasted on a Prosecco and sparkling Shiraz from Barossa but she also had to answer theory questions on Crémant de Limoux and the transfer method that was developed for German Sekt but became hugely popular in Australia & New Zealand. While there are tons of books on Champagne, I’ve yet to find another book that extensively covers these other sparkling wines as well as the Christie’s encyclopedia.

Changes in the new edition

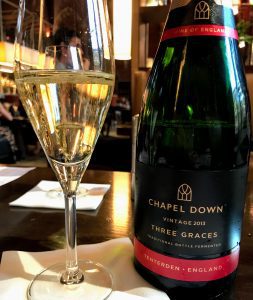

Global warming has made England an exciting region for sparkling wine. The revised edition of Christie’s Encyclopedia has 17 page devoted to the sparklers of the British Isles.

Tom Stevenson wrote the first Christie’s Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine back in the late 1990s. That edition tallied 335 pages while the newest edition (2013) has 528 pages with more than half of those pages covering other notable sparkling wine regions like England, Franciacorta, Tasmania and more. The new edition also has a fresh perspective and feel with the addition of Champagne specialist Essi Avellan as a significant contributor.

In addition to covering the terroir and characteristics of more than 50 different regions, the Christie’s encyclopedia also includes over 1,600 producer profiles. The profiles are particularly helpful with the major Champagne houses as they go into detail about the “house style” and typical blend composition of many of their wines.

Champagne [Boxed Book & Map Set]: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the Iconic Region by Peter Liem. (Used starting $36.57)

The long time scribe of the outstanding site ChampagneGuide.net, Peter Liem is the first author I’ve came across that has taken a Burgundian approach towards examining the terroirs of Champagne.

For a region that is so dominated by big Champagne houses who blend fruit from dozens (if not hundreds) of sites, it’s easy to consider terroir an afterthought. After all, isn’t Champagne all about the blend?

But Champagne does have terroir and as grower Champagnes become more available, wine lovers across the globe are now able to taste the difference in a wine made from Cramant versus a wine made from Mailly.

In-depth Terroir

Several of the most delicious Champagnes I’ve had this year have came from the Côte des Bar–like this 100% Pinot blanc from Pierre Gerbais.

Yet, historically, this region has always been considered the “backwoods” of Champagne and is given very little attention in wine books.

Liem’s work goes far beyond just the the terroir of the 17 Grand Cru villages but deep into the difference among the different areas of the Côte des Blancs, Montagne de Reims, the Grande Vallée, the Vallée de la Marne, Côteaux Sud d’Épernay, Côteaux du Morin, Côte de Sézanne, Vitryat, Montgueux and the Côte des Bar.

Most books on Champagne don’t even acknowledge 6 of those 10 sub-regions of Champagne!

Not only does Liem discuss these differences but he highlights the producers and vineyards that are notable in each. No other book on Champagne goes to this level of detail or shines a light quite as brightly on the various terroirs and vineyards of Champagne.

The best comparisons to Liem’s Champagne are some of the great, in-depth works on the vineyards of Burgundy like Marie-Hélène Landrieu-Lussigny and Sylvain Pitiot’s The Climats and Lieux-dits of the Great Vineyards of Burgundy, Jasper Morris’ Inside Burgundy and Remington Norman’s Grand Cru: The Great Wines of Burgundy Through the Perspective of Its Finest Vineyards.

Liem’s book also comes with prints of Louis Larmat’s vineyard maps from the 1940s. While I’m a big advocate of buying used books, these maps are worth paying a little more to get a new edition. This way you are guaranteed getting the prints in good condition. I’m not kidding when I say that these maps are like a wine geek’s wet dream.

Bursting Bubbles: A Secret History of Champagne and the Rise of the Great Growers by Robert Walters (New available for $18.14)

I did a full review of Bursting Bubbles earlier this year and it remains one of the most thought-provoking books that I’ve read about wine.

If you think I get snarky about Dom Perignon, wait till you read Walters take on the myths surrounding him and the marketing of his namesake wine.

Walters believes that over the years that Champagne has lost its soul under the dominance of the big Champagne houses. While he claims that the intent of his book is not to be “an exercise in Grandes Marques bashing”, he definitely heaps a fair amount of scorn on the winemaking, viticulture and marketing practices that have elevated the Grandes Marques to their great successes.

Throughout the book he “debunks” various myths about Champagne (some of which I personally disagree with him on) as well as interviews many of influential figures of the Grower Champagne movement.

While there is value in Bursting Bubbles from a critical thinking perspective, it is in those interviews where this book becomes essential for wine students. There is no denying the importance of the Grower Champagne movement in not only changing the market but also changing the way people think about Champagne. Growers have been key drivers in getting people to think of Champagne as a wine and not just a party bottle.

Serious students of wine need to be familiar with people like Pascal Agrapart, Anselme Selosse, Francis Egly, Jérôme Prévost and Emmanuel Lassaigne. Walters not only brings you into their world but puts their work into context. While other Champagne books (like Christie’s, Peter Liem’s and David White’s) will often have profile blurbs on these producers, they don’t highlight why you need to pay attention to what these producers are doing like Bursting Bubbles does.

Champagne: How the World’s Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times by Don and Petie Kladstrup. (Used starting at $1.90)

In wine studies, it’s so easy to get caught up in the technical details of terroir, grape varieties and winemaking that you lose sight of a fundamental truth. Wine is made by people.

Of course, the land and the climate play a role but the only way that the grape makes its way to the glass is through the hands of men and women. Their efforts, their story, marks every bottle like fingerprints. To truly understand a wine–any wine–you need to understand the people behind it.

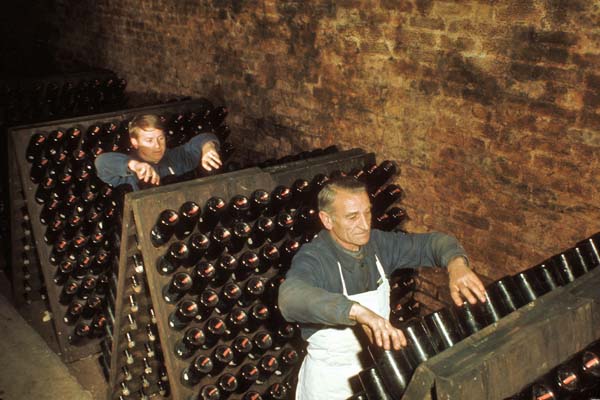

During the height of World War I, when the vineyards and streets of Champagne were literal battlefields, the Champenois descended underground and lived in the caves that were used to aged Champagne.

This photo shows a makeshift school that was set up in the caves of the Champagne house Mumm.

While there are great history books about Champagne (one of which I’ll mention next), no one has yet brought to life the people of Champagne quite as well as the Kladstrups do in Champagne.

Set against the backdrops of the many wars that have scarred the region–particularly in the 19th & 20th century–the Kladstrups share the Champenois’ perseverance over these troubles. Even when things were at their bleakest, the people of Champagne kept soldiering on, producing the wine that shares their name and heritage.

If you wonder why wine folks have a tough time taking sparkling wines like Korbel, Cook’s and Andre’s (so called California “champagnes”) seriously, read this book. I guarantee that you will never use the word Champagne “semi-generically” again.

It’s not about snobbery or marketing. It’s about respect.

But First, Champagne: A Modern Guide to the World’s Favorite Wine by David White (Used starting at $6.00)

David White is known for founding the blog Terroirist. He gives a great interview with Levi Dalton on the I’ll Drink To That! podcast about his motivations for writing this book. While he acknowledges that there are lots of books about Champagne out on the market, he noticed that there wasn’t one that was deep on content but still accessible like a pocket guide.

While the producer profiles in the “pocket guide” section of the book overlaps with the Christie and Liem’s books (though, yes, much more accessible) where White’s book becomes essential is with his in-depth coverage on the history of the Champagne region.

A Tour of History

A watershed moment for sparkling Champagne was in 1728 when Louis XV struck down the laws that prohibited shipping wine in bottles. Prior to this, all French wines had to be shipped in casks.

Soon after, as White’s book notes, the first dedicated Champagne houses were founded with Ruinart (1729) and Chanoine Frères (1730).

The first section of the book (Champagne Through The Ages) has six chapters covering the history of the Champagne region beginning with Roman times and then the Franks to Champagne’s heritage as a still red wine. It continues on to the step-by-step evolution of Champagne as a sparkling wine. These extensively detailed chapters highlights the truth that sparkling Champagne was never truly invented. It was crafted–by many hands sculpting it piece by piece, innovation by innovation.

There are certainly other books that touch on these history details like Hugh Johnson’s Vintage: The Story of Wine (no longer in print), Kolleen M. Guy’s When Champagne Became French, Tilar J. Mazzeo’s The Widow Clicquot as well as previous books mentioned here. But they all approach Champagne’s history from different piecemeal perspectives while White’s work is a focused and chronological narrative.

I also love in his introduction how White aptly summarizes why Champagne is worth studying and worth enjoying.

“From dinner with friends to a child’s laughter or a lover’s embrace, every day has moments worth the warmth of reflection—and worthy of a toast.

Life is worth celebrating. And that’s why Champagne matters.” — David White, But First, Champagne

It is indeed and, yes, it does.

Food & Wine recently published an article by

Food & Wine recently published an article by