During the baseball season in Seattle, there’s a curious event that happens every year when the Toronto Blue Jays visit Safeco Field to play the Mariners.

While I’m a huge baseball fan, I never really followed the Mariners much. However, working at wine shops along the I-5 corridor connecting Vancouver to Seattle, I was always acutely aware of when the Blue Jays were in town.

Because then I would get a massive run on J. Lohr Seven Oaks Cabernet Sauvignon and Kim Crawford Sauvignon blanc.

It was bizarre how cases I would be sitting on for weeks would suddenly vanish in a mist of maple leafs and excessive politeness. When I talked to these customers to understand why these two wines seemed to be the national drink of Canada, I would hear a familiar response.

“Oh, you won’t believe how expensive these are up in Canada!”

Or $23 in Toronto

When I traveled to British Columbia and Toronto with the wife for curling tournaments, I saw first hand how right they were.

That $13 bottle of J. Lohr Cab back in the US? $24

That $11 bottle of Kim Crawford? $18-20

That $5 bottle of Yellow Tail Shiraz? $12

That $7 bottle of Ch. Ste. Michelle Riesling? $16-18

Now some of that is obviously because of the exchange rate (currently 1 USD to 1.31 Canadian). But that would only make those J. Lohr and Kim Crawford bottles around $17 and $14. A significant contributor to the disparity is the local taxes and various tariffs that the Canadian government imposes on wine.

Canada has had a long history of protectionist tariffs–which used to be much higher. This CBC broadcast from 1987 when the original NAFTA negotiations were taking place is well worth the 6:38 to watch. There were stark fears that lowering tariffs (which were as high as 66% in Ontario) would be the end of the Canadian wine industry.

— Amber @ SpitBucket.net (@SpitbucketBlog) December 20, 2019

Note: I wanted to embed the video directly, but apparently CBC’s website and WordPress don’t get along.

Of course, those concerns were unfounded.

And, in fact, Canadian wines got better because the increased competition pushed producers to improve. You can see a microcosm of this quality movement in the CBC video (4:33) when they interviewed Harry McWatters at his Sumac Ridge Estate vineyard.

As they showed McWatters working in the vineyard, my eyes popped at the 5:01 mark seeing the overhead sprinkler system they were using for irrigation. This is something that California and a lot of major wine regions started phasing out back in the 1970s as drip irrigation became more widely available. Moving away from wasteful overhead systems towards understanding the importance of controlled deficit irrigation has been a harbinger of quality improvement in many regions.

But you can also see from the interview that McWatters was convinced that he could compete with small, quality-minded producers in California. Clearly, over the next couple of decades, he put that faith into practice as evidenced by Master of Wine James Cluer’s 2012 visit to Sumac Ridge (7:46).

Starting at the 1:40 mark, Cluer interviews McWatters’ daughter, Christa-Lee McWatters Bond, who described many of the changes her dad did in response to the free trade agreement–including pulling out hybrid varieties to plant more vinifera.

However, there is still more work to do.

While the quality of Canadian wine is rapidly improving, the high prices of foreign wine continue to be a crutch that holds them back. This is always the folly that comes with limiting competition.

Think about this. In the minds of many Canadian consumers, J. Lohr Seven Oaks is the benchmark standard of a $24 wine. So how much effort then do Canadian wineries need to put in to make a better $20-25 bottle? Certainly not the same amount that producers in Washington State, Oregon and California need to do where consumers who are looking to spend $20-25 aren’t thinking about J. Lohr Seven Oaks.

It’s hard to imagine paying $20 retail for Kim Crawford when stuff like Gramercy’s Picpoul (or $10-15 French Picpoul de Pinet) exists.

Instead, those consumers are looking at wines like:

Chateau Ste Michelle’s Borne of Fire and Intrinsic

Gordon Estate Cabernet Sauvignon

Adelsheim Willamette Valley Pinot noir

Ponzi Tavola Pinot noir

Elk Cove WV Pinot noir

Schug Carneros Pinot noir

Au Bon Climat Santa Barbara Pinot noir

Stags’ Leap Merlot

Trefethen Double T Meritage

Heitz Zinfandel

BV Napa Valley

Or, for a few dollars more, J. Lohr’s Paso Robles Hilltop Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon.

That’s before you even get to loads of compelling values from Australia, South America and Europe as well.

Yes, there is always a risk that consumers will choose these better value options from somewhere else. But the answer to that problem is to raise the bar, not artificially lower it with protectionist taxes and tariffs.

The US is at risk of making the same mistake.

There’s been lots of ink spilled over the recent threat from the US government to slap 100% tariffs on European wines such as Champagne. The primary justification for these threats is “unfair” trade practices, with some thinking that domestic American wineries will benefit from consumers turning away from more expensive European wines.

Already wine writers are penning posts about how folks can “drink around” the tariffs–noting many domestic options as well as countries that are not yet being hit by tariffs.

But it’s extremely telling that many American wine producers, as well as the US Wine Institute, are firmly against the proposed tariffs.

On Twitter, Jason Lett of Eyrie Vineyards in Oregon shared the letter that he sent to the US trade ambassador.

@jbonne Thanks for bringing this to our attention. I just submitted the following letter of testimony in opposition to these damaging tariffs.@WineAmerica @oregonwineboard pic.twitter.com/4MDCKlctaf

— Jason Lett (@JasonLett) December 19, 2019

Lett brings up numerous excellent points about the impacts of retaliatory tariffs in other markets (which is already being felt in China). However, he touches on the pratfalls of limiting consumer choice.

Here Lett looks at it from the angle of distributors being hampered in providing a diverse portfolio. However, the lessons of those Blue Jay Weekends in Seattle still echos.

US wines are better when they’re striving to be the best.

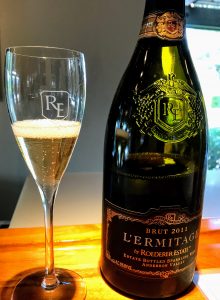

Things like Roederer L’Ermitage from California already out-drink many Champagnes. Using tariffs to push up the price of Veuve Clicquot to $60 is not going to make this sparkler more outstanding.

From the fanatical quest of Martin Ray and Robert Mondavi to make wines on par with the greats of Europe to the legendary Judgement of Paris wines that beat them, the American wine industry has succeeded by raising the bar and not settling.

It’s the competition of outstanding Champagne at affordable prices that inspires high-quality producers in Oregon and elsewhere to keep driving. Otherwise, why not settle for Korbel?

The fabulous rosés of Provence put into context how incredibly delicious Bedrock’s Ode to Lulu, DeLille and other American rosés can be.

It’s the high benchmark of Savennières and the Mosel that encourages folks like Tracey & John Skupny and Stu Smith to make some of the best white wines in California.

Likewise, Anna Shafer of àMaurice in Walla Walla doesn’t need the bar artificially lowered with more expensive French white blends to have a reason to chase after the heights of Condrieu with her Viogniers.

It’s a trap to get complacent and think that pricing or placement is going to win the day. Yeah, that protectionism might give you a short term buffer, but it comes at a cost.

After all, how much of a victory is it to have consumers singing your anthem in another stadium if they’re drinking someone else’s wine?