![By Joseph Faverot - [1], Public Domain, on Wikimedia Commons](http://spitbucket.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Wikimedia-Champagne-clow-242x300.png) Last week I got into a bit of a tizzy over some ridiculous things posted by a so-called “Wine Prophet” on how to become a “Champagne Master.” See Champagne Masters and their Bull Shit for all the fun and giggles.

Last week I got into a bit of a tizzy over some ridiculous things posted by a so-called “Wine Prophet” on how to become a “Champagne Master.” See Champagne Masters and their Bull Shit for all the fun and giggles.

But despite the many failings of Jonathan Cristaldi’s post, he did dish out one excellent piece of advice. To learn more about Champagne, you have to start popping bottles. I want to expand on that and offer a few tidbits for budding Champagne geeks.

I’m not going to promise to make you a “Champagne Master”–because that is a lifelong pursuit–but I will promise not to steer you towards looking like a buffoon regurgitating nonsense about Marie Antoinette pimping for a Champagne house that wasn’t founded till 40+ years after her death.

Deal? Alright, let’s have some fun.

1.) Start Popping Bottles!

Pretty much you can stop reading now. I’m serious. Just try something, anything. Better still if it is something you haven’t had or even heard of before. Pop it open and see what you think.

They say it takes 10,000 hours to master anything so take that as a personal challenge to start getting your drink on. Well actually that 10,000-hour thing has been debunked, but mama didn’t raise a quitter.

Though seriously, if you want to make your tasting exploration more fruitful, here are some tips.

Make friends with your local wine shop folks

They pretty much live and breath the wines they stock. They know their inventory. The good ones also have a passion to share their love and knowledge with others. Admittedly not every shop is great but go in, look around, ask questions and see if you find a good fit. Finding a great local wine shop with folks whose opinions you trust is worth its weight in gold for a wine lover. Once you’ve found that, the door is open for you to discover a lot of fantastic bottles that will only enrich your explorations.

Learn the differences between négociant houses, grower-producers and co-operatives

Online retailers can be helpful as well but sometimes it’s good to have a face to put with a bottle.

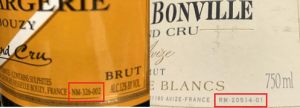

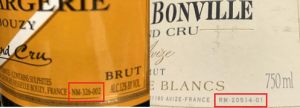

In Champagne, you can often find on the label a long number with abbreviations that denote what type of producer made the Champagne.

NM – négociant manipulant, who buy fruit (or even pre-made wine) from growers. These are the big houses (like the LVMH stable of Moët & Chandon & Veuve Clicquot) that make nearly 80% of all Champagne produced. These Champagnes aren’t bad at all. Most are rather outstanding.

But the key to know is that while there are around 19,000 growers, the Champagne market is thoroughly dominated by several large négociant houses. Chances are if you go into a store (especially a grocery store or Costco), these wines are likely going to be your only options. You should certainly try these wines. However, it’s worth the leg work to find the whole wide world of Champagne that exists beyond these big names. This is a huge reason why making friends at the local wine shop (who often stock smaller producers) is a great idea.

But here is where it gets exciting.

RM – récoltant manipulant, who make wine only from their own estate fruit. These are your “Grower Champagnes” and while being a small producer, alone, is not a guarantee of quality, exploring the wines of small producers is like checking out the small mom & pop restaurants in a city instead of only eating at the big chain restaurants. You can find a lot of gems among the little guys who toil in obscurity.

CM – coopérative-manipulant, who pool together the resources of a group of growers under one brand. This is kind of the middle ground between true Grower Champagne and the big négociant houses. Some of these co-ops are small and based around a single village (like Champagne Mailly) while others cover the entire region (like Nicolas Feuillatte which includes 5000 growers and is one of the top producers in Champagne). Some of these are easier to find than others, but they are still worth exploring so you can learn about the larger picture of Champagne.

An example of a négociant (NM on left) and grower (RM on right) label.

Pay attention to sweetness and house style

While “Brut” is going to be the most common sweetness level you see, no two bottles of Brut are going to be the same. That is because a bottle of Brut can have anywhere from Zero to up to 12 grams per liter of sugar. Twelve grams is essentially 3 cubes of sugar. Then, almost counter-intuitively, wines labeled as “Extra Dry” are going to actually be a little sweeter than Brut. (It’s a long story)

Though to be fair, if they served Champagne at McDonald’s, I would probably eat there more often. It is one of the best pairings with french fries.

This is important to note because while Champagne houses often won’t tell you the dosage (amount of sugar added at bottling) of their Bruts, with enough tasting, you can start to discern the general “house style” of a brand.

For instance, the notable Veuve Clicquot “Yellow Label” is tailor-made for the sweet tooth US market and will always be on the “sweeter side of Brut” (9-12 g/l). While houses such as Billecart-Salmon usually go for a drier style with dosages of 7 g/l or less. If you have these two wines side by side (and focus on the tip of your tongue), you will notice the difference in sweetness and house style.

The idea of house style (which is best exhibited in each brand’s non-vintage cuvee) is for the consumer to get a consistent experience with every bottle. It’s the same goal of McDonald’s to have every Big Mac taste the same no matter where you are or when you buy it. All the dominant négociant houses have a trademark style and some will be more to your taste than others.

Explore the Grand Crus and vineyard designated bottles

While Champagne is not quite like Burgundy with the focus on terroir and the idea that different plots of land exhibit different personalities, the region is still home to an abundance of unique vineyards and terroir. You can best explore this through bottles made from single designated vineyards. However, these can be expensive and exceedingly hard to find.

Quite a bit easier to find (especially at a good wine shop) are Grand Cru Champagnes that are made exclusively from the fruit of 17 particular villages. There are over 300 villages in Champagne but over time the vineyards of these 17 villages showed themselves to produce the highest quality and most consistent wines. All the top prestige cuvees in Champagne prominently feature fruit from these villages.

To be labeled as a Grand Cru, the Champagne has to be 100% sourced only from a Grand Cru village. It could be a blend of several Grand Cru villages but if a single village is featured on the front of the label (like Bouzy, Mailly, Avize, Ambonnay, etc) then it has to be only from that village. Since the production of the Grand Cru villages represents less than 10% of all the grapes grown in Champagne, you would expect them to be somewhat pricey. That’s not the case. Many small growers have inherited their Grand Cru vineyards through generations of their families and can produce 100% Grand Cru Champagnes for the same price as your basic Champagnes from the big négociant house.

Well worth the hunt

They may be a little harder to find than the big négociant houses, but Grand Cru Champagnes from producers like Pierre Peters, Franck Bonville, Pierre Moncuitt, Petrois-Moriset, Pierre Paillard and more can be had in the $40-60 range.

While not as terroir-driven as single vineyard wines, tasting some of the single-village Grand Crus offers a tremendous opportunity to learn about the unique personality of different villages in Champagne and is well worth the time of any Champagne lover to explore.

2.) Great Reading Resources

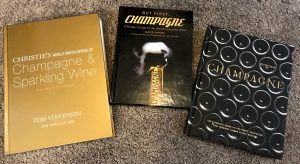

Truthfully, you can just follow the advice of the first step and live a life of happy, bubbly contentment. You don’t need book knowledge to enjoy Champagne–just an explorer’s soul and willingness to try something new. But when you want to geek out and expand your experience, it is helpful to have robust and reliable resources. There are tons of great wine books dealing with Champagne and sparkling wine but a few of my favorites include:

A few favs

Tom Stevenson and Essi Avellan’s Christie’s World Encyclopedia of Champagne & Sparkling Wine — The benchmark reference book written by the foremost authorities on all things that sparkle.

Peter Liem’s Champagne [Boxed Book & Map Set] — This set ramps up the geek factor and dives deeper into the nitty-gritty details of Champagne. The companion maps that shows vineyards and crus of the region are enough to make any Bubble Head squeal.

David White’s But First, Champagne — A very fresh and modern approach to learning about Champagne. It essentially takes the Christie’s Encyclopedia and Peter Liem’s opus and boils it down to a more digestible compendium.

Robert Walter’s Bursting Bubbles — Thought-provoking and a different perspective. You can read my full review of the book here.

Don & Petie Kladstrup’s Champagne: How the World’s Most Glamorous Wine Triumphed Over War and Hard Times — One of my favorite books, period. Brilliantly written work of historical non-fiction about the people who made Champagne, Champagne. If you ever wondered what was the big deal about people calling everything that has bubbles “champagne,” read this book about what the Champenois endured throughout their history and you will have a newfound respect for what the word “Champagne” means.

Ed McCarthy’s Champagne for Dummies — A little outdated but a quick read that covers the basics very well. I suspect that if the “Wine Prophet” read this book, he wouldn’t have had as many difficulties understanding the differences between vintage and non-vintage Champagnes.

3.) Next Level Geekery

As I said in the intro, the pursuit of Champagne Mastery is a lifelong passion and you never stop learning. Beyond the advice given above, some avenues for even more in-depth exploration includes:

The Wine Scholar Guild Champagne Master-Level course — I’ve taken the WSG Bordeaux and Burgundy Master courses and can’t rave enough about the online programs they have. Taught by Master Sommeliers and Masters of Wine, the level of instruction and attention to detail is top notch. They also offer immersion tours to the region.

Jancis Robinson’s Purple Pages — This Master of Wine is one of the most reliable sources for information and tasting notes on all kinds of wine but particularly for Champagne.

Allen Meadow’s Burghound — While Burgundy is Meadow’s particular focus, he does devote a lot of time reviewing and commenting on Champagne and, like Robinson, is a very reliable source. But the caveat for all critics is to view them as tools, rather than pontiffs.

Visit Wineries

If you get a chance to riddle, it will be enjoyable for the first couple of minutes. Then you realize how hard of a job it is.

Even if you can’t visit Champagne itself, chances are you are probably near some producer, somewhere who is making sparkling wine.

Throughout the world, producers making bubbly. From African wineries in Morocco, Kenya, Zimbabwe and South Africa; Asian wineries in China and India; to more well known sparkling wine producing countries in Australia, Argentina, Chile, United Kingdom and Eastern Europe–the possibilities are near endless.

Even in your own backyard

In the United States, there is not only a vibrant sparkling wine industry in the traditional west coast regions of California, Oregon (Beaver State Bubbly) and Washington State but also New Mexico, Missouri, New York, Virginia, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, Georgia, Colorado and more.

While they may not be doing the “traditional method,” there is still benefit to visiting and tasting at these estates. At small wineries where the person pouring could be the owner or winemaker themselves. These experiences can give you an opportunity to peek behind the curtain and see the work that happens in the vineyard and winery. As beautiful of a resource that books and classes are, there is no substitute for first-hand experience.

So have fun and keep exploring!

A few quick thoughts on the 2015

A few quick thoughts on the 2015

![By Joseph Faverot - [1], Public Domain, on Wikimedia Commons](http://spitbucket.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Wikimedia-Champagne-clow-242x300.png) Last week I got into a bit of a tizzy over some ridiculous things posted by a so-called “Wine Prophet” on how to become a “Champagne Master.” See

Last week I got into a bit of a tizzy over some ridiculous things posted by a so-called “Wine Prophet” on how to become a “Champagne Master.” See

A few thoughts on

A few thoughts on