One of my favorite study techniques is to guess potential questions on exams. Even if my guesses are entirely off, the studying that I do to answer these hypothetical questions is always worthwhile.

While prepping for the WSET Diploma sparkling wine exam in January, I’ve been jotting down a few possible topics. One, in particular, I keep coming back to.

What are some things in the vineyard and winery that Champagne producers can do in response to climate change & riper vintages?

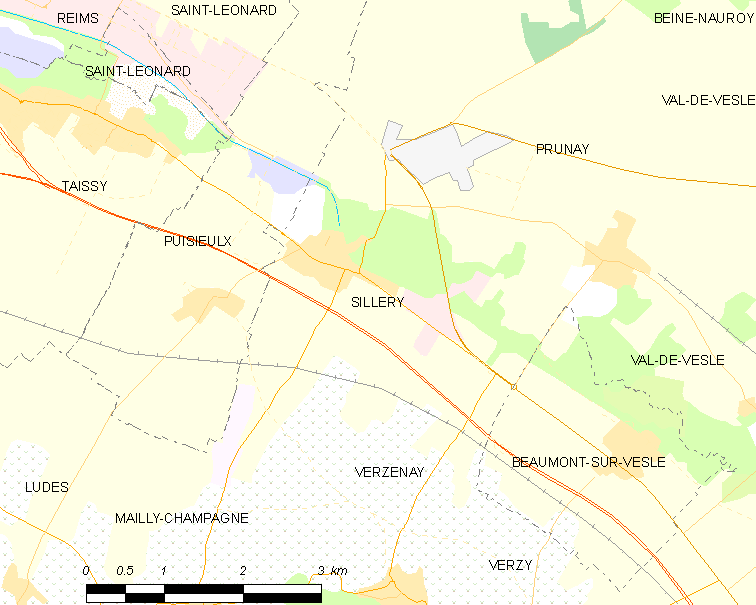

Now the viticulture part of this question is fairly straightforward. There are numerous tacts you can take–beginning with seeking cooler sites (particularly north-facing slopes) and exploring new (or rather historic) grape varieties that ripen later with more acidity. Likewise, houses like Pierre Peters are experimenting with new clones as well. Of course, those require replanting with significant time and cost commitments.

A little less expensive would be changing trellising and canopy management approaches. Raising the fruiting zone higher and leaving more leaves encourages shading, which keeps the grapes cooler. Shade screens (that can also function as netting against birds) as well as using kaolin clay as sunscreen for grapes are other options. Champagne Bruno Paillard is doing an intriguing experiment with using straw in the vineyard to block sunlight from impacting the microflora in the soil.

But taking this question into the winery is a little more difficult–at least regarding Champagne.

Storage tanks at Champagne Joly.

Today many Champagne houses are relying more on higher acid reserve wines to add freshness to their non-vintage cuvees.

In many warm regions, the first tools out of the winemaker’s belt for dealing with overripe grapes are watering back and acidification. Technically, these aren’t permitted in cool-climate (Zones A & B) regions of the EU. However, in warm vintages like 2003, special dispensations can be given.

Other options include blending and various alcohol removal techniques like reverse osmosis and spinning cones. While the former is part and parcel in Champagne, the later may be more challenging to use.

Sweet spotting in wine is highly variable and sensory-driven. Anything done to the vin clair is going to get magnified during the secondary fermentation process–including imbalances with flavor. Plus, it’s important to note that the secondary fermentation adds 1 to 1.5% alcohol to the finished wine as well.

However, as I taste through many Champagnes in preparation for my exam (dreadful work, I know), I find myself being continually drawn to certain bottles. These wines crackle with lively fruit flavors that make an immediate impression on the palate.

Researching further, I found a common link between many of these Champagnes. They all tend to have little or no malolactic fermentation (MLF) done.

How common is MLF in Champagne?

Incredibly common. It’s almost standard protocol for a region that has historically had to battle racy high acidity. Some estimates are that as much as 90% of all Champagnes go through some malolactic fermentation.

While lactic acid formed during MLF is considered a softer acid than malic, it’s important to remember that lactic acid is the critical component in sourdough and turning cabbage into sauerkraut.

Running a wine through MLF can drop the titratable acidity (TA) 1-3 g/l and raise the pH 0.3. This will have a significant effect on the mouthfeel of a Champagne–rounding it out and making it feel less austere. In addition to the tactile characteristics, Champagnes that go through full malo tend to have more dried fruit and nutty aromas to go with the brioche and buttery pastry traits of this style.

But more than just seeking the smoother, rounder mouthfeel that MLF brings is the importance of stability. Beyond consuming malic acid, the Oenococcus bacteria gobble up any residual nutrients left in the wine that could be prey for spoilage organisms. As noted above, secondary fermentation is like a high power magnifying glass that makes every quirk, characteristic or flaw of the vin clair more apparent.

However, running Champagnes through malolactic fermentation hasn’t always been standard in Champagne.

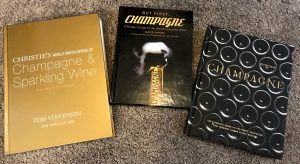

As Peter Liem describes in his book, Champagne (one of the five essential books on Champagne), MLF only became widespread in the 1960s.

This coincided with the renovation of many wine cellars with modern technology like stainless steel tanks that could regulate temperature better. MLF is inhibited in cold temperatures below 55°F (13°C), so being able to warm the must in winter is critical. Likewise, inoculated cultures that were more predictable and dependable became widely available. Many consumers found the Champagnes that went through full malo were richer and approachable younger–encouraging more experimentation with MLF.

Rebels or Vanguards?

Several houses did buck the trend of adopting MLF though. The most notable of these are Alfred Gratien, Gosset and Lanson. However, in recent years, Lanson introduced some styles with partial malo.

The barrel room at Champagne Lanson

Gosset has also started to take the approach of Krug and Salon in that they don’t encourage MLF, but don’t actively try to prevent it either. This means that some batches may go through malo but, on the whole, the style of house is non-malolactic.

Krug is an interesting case. Because despite the ambivalence towards intentional MLF, their house style is decidedly rich and powerful like many full MLF wines. This is partly because of their use of small (205L) oak barrels to ferment in, extended lees aging and, in the case of their multi-vintage Grande Cuvée, the extensive use of reserve stocks.

As I went through my tasting notes, I found several of the partial-to-no-MLF houses similarly make use of oak barrels. These include Gratien, AR Lenoble, Bérêche, Camille Savès, Eric Rodez, Lanson, Laherte Frères, Nicolas Maillart, Perseval, Savart, Thevenet-Delouvin, Vilmart and Louis Roederer. Most intriguing, though, was that these Champagnes rarely tasted oaky.

Instead, these wines were fresh & vibrant with a searing expression of fruit character that felt lost in many of their “rounder” cousins. In a world of circles, these were wines with edges. They stood out and, in a crowded market place, that’s always a plus.

But the big question is–with rising temperatures and riper vintages pushing down acidity, are we going to see more wineries deliberately blocking malolactic fermentation?

Champagne houses that practice partial and no MLF

While I’ve mentioned several above already, here is the full list of Champagnes that I’ve encountered so far who don’t do full malo on all their wines. If you know of other estates, feel free to leave a comment and I’ll get them added to the list.

To my fellow wine students, I highly recommend making it a priority to taste Champagnes with little to no MLF side by side with their more prevalent malo counterparts. You can definitely pick up the stylistic differences.

Gosset Grand Reserve Brut.

Alfred Gratien

AR Lenoble (partial though in recent vintages it has been blocked completely)

Bérêche et Fils

Besserat de Bellefon

Guy Charlemagne (partial)

Gosset (Most no MLF. Partial with Brut Excellence NV)

Krug

Laherte Frères (partial for some cuvees. Completely blocked on others.)

Lanson (partial for Black Label. Completely blocked on others)

Roger-Constant Lemaire

Nicolas Maillart (partial)

José Michel & Fils (partial)

Louis Nicaise (partial)

Franck Pascal (partial)

Pehu-Simonet

Perseval-Farge (partial)

Eric Rodez (partial)

Louis Roederer (partial with the Brut premier and sometimes Cristal rose. Completely blocked on others.)

Salon

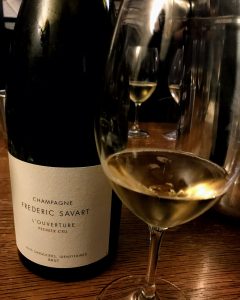

Frédéric Savart (partial)

Camille Savès

Thevenet-Delouvin (partial)

Vazart-Coquart & Fils (partial)

J.L. Vergnon

Maurice Vesselle

Vilmart & Cie

Philipponnat

Frédéric Savart L’Ouverture Brut

BTW, while researching this piece, I found that Tyson Stelzer’s article “Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble” answered my hypothetical WSET question almost perfectly. If you’re a WSET Diploma student, his site is well worth checking out.

Food & Wine recently published an article by

Food & Wine recently published an article by