Back in 2013, GuildSomm did a fantastic podcast with Frédéric Panaiotis (39:33) of the Champagne house Ruinart about how Champagne is made. They followed it up with another interview with Panaiotis this year on Champagne (44:54) that also featured Rodolphe Péters of Pierre Péters.

Both shows are chock-full of awesome behind-the-scenes insights about Champagne that are well worth listening to. I’m going to break down the 2013 episode here first and then devote another Geek Notes to the second interview.

But after doing multiple Geek Note reviews of various podcasts (like Grape Radio’s interview with Hubert de Boüard of Ch. Angélus, UK Wine Show episode with Ian D’Agata about Italian wine grapes, Wine For Normal People’s episode on Tuscan wine regions and I’ll Drink To That! interview with Greg Harrington on Washington wine), I realize that I should take a moment to explain the objective of these posts.

Highlighting Learning Tools That I Use

As I mentioned in my post SpitBucket on Social Media, the purpose of my Geek Notes features are to highlight valuable resources for wine students pursuing various certifications.

Wine podcasts are a big focus for me because I think they’re often extremely underutilized. It’s easy for wine students to bury their heads in books and create flash cards. But we shouldn’t discount that nearly a third of individuals are auditory learners. Furthermore, for the 65% who are visual learners, exposing ourselves to audio avenues helps reinforce the material that we’re learning.

However, most people are actually a mix of multiple learning styles so the best approach is to also incorporate kinesthetic (hands-on) learning as well.

This is essentially what I’m doing for myself with these Geek Note reviews of podcasts. I’m primarily a visual learner so I’m always diving into one wine book or another. But when I’m going deep on a topic, I supplement that book learning by listening to related podcasts.

When I come across a podcast with useful information, I go back to listen to it a second time. This time, I take notes. It’s like recording your class lectures back in college. You spend class time actually listening to the instructor and absorbing the material first without distracting scribbling and note taking. But then you solidify the material in your mind by going back to the recorded lecture for notes.

A little bit of a review element.

While I’ll include timestamps, I don’t really intend for these posts to be transcriptions. If I’m doing a review of a podcast, it’s because I feel that it is sincerely worth listening to. There will often be contextual tidbits and stories featured in these episodes that I won’t mention or fully address. You can get more out of these Geek Notes by checking out the podcasts for yourself after reading these posts.

For newer podcasts like my recent reviews of the Decanted podcast and the Weekly Wine Show, I’ll spend more time giving background about the podcast and why I think they’re worth subscribing to.

In many ways, great wine podcasts are like stellar reference books like The Oxford Companion to Wine, The World Atlas of Wine and The Wine Bible. They provide you with an entire library of wine knowledge that you can digest one entry at a time.

In the next Geek Notes, I’ll give a little background about GuildSomm but, right now, let’s dive right into their podcast interview with Frédéric Panaiotis on making Champagne.

Fun Things I Learned From This Podcast

Statue of Dom Thierry Ruinart (1657-1709) outside the Champagne house Ruinart in Reims.

(0:52) Prior to joining Ruinart, Frédéric Panaiotis also previously worked for Veuve Clicquot, the CIVC as well as the California sparkling wine producer Scharffenberger in the Anderson Valley of Mendocino.

(3:16) Historically, the CIVC used to set one general ban des vendanges for the region. This is the first day that grapes can be legally harvested. Now there are multiple ban des vendanges based not only on the village but also on the individual grape variety. And apparently rootstock in some cases too.

For instance, in the Grand Cru village of Mailly for the 2018 vintage they were allowed to start picking Pinot Meunier on August 25th. However, for Chardonnay and Pinot noir (which the village is most noted for), growers had to wait till August 27th.

I’m curious about the ban des vendanges for other grape varieties–Fromenteau/Pinot gris, Pinot blanc, Petite Meslier and Petite Arbanne. I couldn’t find the answer online but I’ll keep looking.

BTW, August start dates were historically unusual in Champagne but are now becoming much more commonplace. This recent 2018 vintage was the fifth year since 2003 to begin in August.

(5:45) You can get a special allowance from the CIVC to harvest earlier. According to Panaiotis, this may be needed if you are harvesting from a really young vineyard of 3 years or were hit by spring frost which drastically reduced yields. Apparently with less clusters to focus on, the vine will accelerate ripening.

That strikes me a bit curious because wouldn’t the same logic apply to old vines which also produce lower yields. Wouldn’t they also ripen faster? Need to research this more.

Harvest Brix and Ripeness

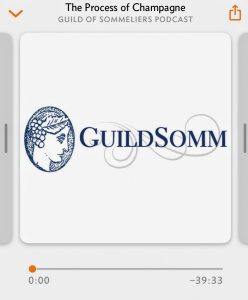

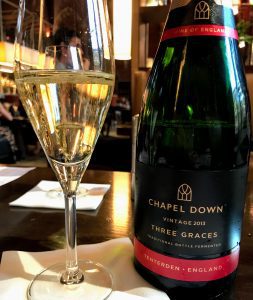

Chardonnay grapes harvested in the village of Vertus.

(6:21) Panaiotis notes that the Champenois usually aim to harvest grapes at around 10% potential alcohol which is about 18-19° Brix. Compare this to typical still wine production where producers want to harvest Chardonnay more at 20-23° Brix and Pinot noir around 25-27°. But, keep in mind, the secondary fermentation of Champagne (where sugar and yeast are added) adds more alcohol to the finish wine. Most Champagnes finish with an ABV in the 12-12.5% range.

(8:00) A big distinction that GuildSomm’s Geoff Kruth and Panaiotis note about Champagne is that even at these low brix levels, the grapes are still ripe. Panaiotis gives the example of the 1988 vintage which was picked at many estates at around 9.2% potential alcohol (17.5° Brix) in a year that was a late harvest for Champagne. This vintage is still highly regarded for its richness and longevity. Yet harvesting something at so low of a brix level in most any other wine region would produce wines abundant in green, unripe flavors.

This is a quandary that sparkling wine producers from warmer climates like California and Spain have to deal with because acidity is also at play. Not only is it hard to get desired ripeness with such low brix but you need to harvest your grapes with ample acidity. While improvements in viticulture and planting in cooler vineyard sites have helped, historically producers from warm regions have needed to harvest the grapes at lower ripeness levels in order to have enough acid to make their sparkling wines.

The Controversial 1996 Vintage

(8:55) In contrast to 1988, Panaiotis describes the 1996 as an “unripe” year even though the grapes were harvested at 10.5% potential alcohol (20° Brix). This is intriguing because there is a lot of controversy going on now about the 1996 vintage which Jancis Robinson aptly explains in one of her Financial Times articles.

When the 1996 Champagnes were first released, many Champagne lovers were enthralled. That year was pegged as one of the top vintages of the 20th century. I will admit that, even though I’ve been extremely underwhelmed by their recent offerings, the 1996 Dom Perignon was one of the greatest wines that I’ve tried in my lifetime. But I had that wine soon after release and it seems that as the 1996s across the board have aged, more and more people are re-evaluating how good that vintage really was.

Challenges of Big Houses

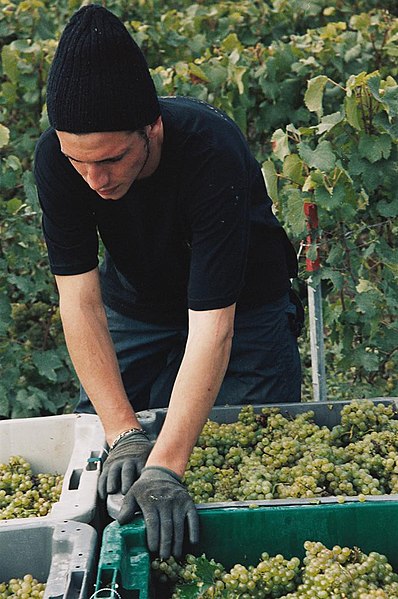

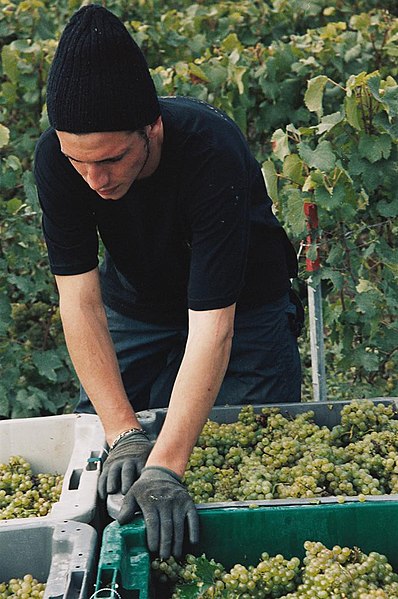

By law, Champagne grapes have to be harvested whole cluster and by hand.

(9:20) Here Panaiotis talks about the challenges that big houses have versus small growers with harvest–particularly with red grapes like Pinot noir. Because the goal in Champagne most often with Pinot is to make a white wine, time is of the essence as soon as you remove the cluster from the vine. You don’t want any “cold soak” color extraction taking place in the pick bin. With Chardonnay, avoiding oxidation of the juice is also a concern for many houses.

But what do you do when you are a large house whose winery is maybe several miles away from the many vineyards you source from? Well worth listening to see how Ruinart responds to this challenge.

(10:30) Machine harvesting is forbidden in Champagne. Part of the reason is because machine harvesters can only harvest individual berries. They do this by using beater bars to separate the berries from clusters on the vine. If you’re curious, this short (2:18) ad video for a mechanical harvester gives a great inside view into how these harvesters work. Panaiotis thinks that even if someone developed a machine that could somehow harvest grapes whole cluster that it would still probably be outlawed.

Pressing Details

A modern bladder press.

(11:54) Panaiotis estimates that among the various presses used in Champagne, about half are modern bladder presses with the rest being the traditional Coquard basket press. Piper-Heidsieck has a quick 1 minute video of the Coquard press in action with Pinot noir. Note how the juice, even with the whole clusters, is already being tinted with color. And, yes, leaves and other MOG often gets thrown into these large batches.

(12:15) In Panaiotis’ opinion, 70-80% of the resulting quality of the wine comes from the pressing process. This is an interesting departure from the opinion that a lot of the quality of Champagne comes from the blending and time aging on the lees. From here he goes into a great description of the different cuts (cuvée and taille) that are separated in the pressing process. To explain this he uses a comparison that you can do in a vineyard while sampling a single grape berry.

(14:47) At Ruinart, Panaiotis likes using the taille for their non-vintage Champagnes. Here these cuts add roundness and fruitiness but there is a trade-off in decreased aging potential. In contrast, Ruinart’s vintage wines are almost all cuvée juice since the lower phenolics in this first cut is less prone to oxidation.

This makes me curious about the pressing philosophy of Champagne houses that value more oxidative styles like Krug.

Fermenting as separate lots or as regional blends

(16:10) When Kruth asks how Champagne producers keep the juice from different villages and vineyards separate, Panaiotis explains some of the logistical problems of that. While it is ideal to keep different villages separate, it may take you several days to receive enough lots from those villages to eventually fill an entire tank. That reality favors blending more regionally–like all the Côte des Blancs villages together.

I suspect this is more of an issue for large Champagne houses who presumably have very large tanks with several thousand liter capacities that need to be filled. Additionally, with so many contract growers there is probably a fair amount of variability in what kind of yield you can expect each year from different villages/vineyards, etc. In contrast, smaller growers who have been tending their own vines for generations probably know more precisely what they are getting and accordingly have smaller tanks that are easier to fill up and keep separate.

Another key point specific to Ruinart is that their house’s style is very reductive. If the tanks aren’t filled quickly, there is a risk of the juice oxidizing before fermentation takes off.

Style Differences

(17:14) At Ruinart, they aim for very clean and neutral flavors in their base wines. Along with wanting to avoid oxidation, they use sulfur on the juice to also knock back wild yeast so that they can inoculate with cultured yeast. Kruth notes that the impact of wild or native ferment produces flavors that get amplified during the secondary fermentation, something Panaiotis wants to avoid at Ruinart.

Lanson is another house that has historically avoided malolactic fermentation but has recently been experimenting with MLF on a few lots.

(19:30) Panaiotis likes the round mouthfeel that comes from initiating malolactic fermentation in the Champagnes of Ruinart. This is a stylistic decision relating to different Champagne house styles. Some producers, most notably Gosset, historically avoid malolactic fermentation so they can maintain natural acidity and aging potential. But the trade-off is mouthfeel and softness with even Gosset experimenting with having some batches going through MLF.

(20:24) A very interesting discussion on the different philosophy of using reserve wines in the blends of non-vintage Champagnes. Panaiotis describes the impact of using older versus young reserve wines on the resulting style of Champagne. He notes that Ruinart’s precise style favors using younger reserve wines while houses with a more mature style like Charles Heidsieck prefer using older reserve wines of up to 10 years of age.

Secondary Fermentation Issues

(24:18) Probably my biggest surprise was learning about the issues of calcium tartrates in Champagne. If wineries don’t remove these unstable tartrates via cold stabilization, there will be excessive foaming during disgorgement. Worst, this foaming could happen when the wine is opened by consumers–creating a mess. I always thought it was more about aesthetics with consumers mistaking the tartrate crystals for shards of glass.

(25:47) Another completely new thing I learned was that the actual length of time of the secondary fermentation is about 6 to 8 weeks. I always thought it was much quicker like primary fermentation which usually takes several days to a couple weeks. Panaiotis does note that as soon as 3 days after bottling you can start to see the dead lees collecting in the bottle.

(26:52) Panaiotis reveals that recent studies of the Champagne process is showing that oxygen intake through the crown cap or cork is just as impactful on the resulting flavor of the wine as autolysis is.

Oxidative vs Reductive

Bollinger Champagnes have been traditionally associated with an oxidative style of winemaking.

(28:22) Panaiotis goes into an in-depth discussion of oxidative versus reductive winemaking. He details many of the decisions that he has to make throughout the process to promote Ruinart’s reductive style including the unique technique of jetting. Here winemakers add a little bit of water or nitrogen (and sometimes sulfur) to the wine before corking to promote foaming that pushes out the oxygen. This short video (0:52) is in French but shows the process well.

(31:10) Kruth asks for example of major houses who follow the different styles. Panaiotis notes that along with Ruinart, Laurent Perrier, Mumm, Pierre Gimonnet, Pierre Moncuit and Pierre Peters are on the reductive side while Bollinger, Krug, Jacquesson and Jacques Selosse are on the oxidative side. He also notes that Pinot noir favors the more oxidative style. Interestingly, most of the houses he mentions that favor a reductive style tend to be Chardonnay dominant.

(37:40) Panaiotis notes that the CIVC legally limits how many grapes negociants can buy each year. While he didn’t seem completely certain, he estimates that the limit is a maximum of 30% above the equivalent of your previous year’s sales. I’m guessing the CIVC sets these rules to prevent stockpiling? But there is no law on the amount of land you can own. Another tidbit from Panaiotis, growers can buy up 5% of their grapes and still be considered a grower producer.