Welcome back! To get the lowdown on the series check out Part I where we explore the exceptions of the Montagne de Reims. In Part III and IV, we’ll check out the Côte des Blancs and the Aube/Côte des Bar.

As for today, we’re heading to the Vallée de la Marne.

The Marne river flowing past Épernay in the early 20th century.

If you’re one of those folks who “know enough to be dangerous” about Champagne, you’ll peg the Vallée de la Marne as the Pinot Meunier corner of the holy triumvirate of Champagne. However, as we noted in part one, neatly pigeonholing these regions with a single variety cuts about as deep as a butter knife.

To really start to “get” Champagne, you have to move beyond the superlatives (and the BS of so-called “Champagne Masters”). This requires looking at legit sources but also getting your hands on detailed maps.

Having good wine maps is an absolute must for any wine student.

Yes, you can find some online. For today’s journey through the Vallée de la Marne, this interactive map from Château Loisel will be useful. But sometimes clicking between computer tabs is annoying compared to a physical map in front of you.

I mentioned the Louis Larmat maps yesterday. But let me give you two more excellent options.

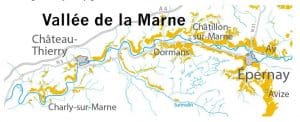

Map of the Vallée de la Marne from the UMC website.

In the lower-right, you can see the start of the Côte des Blancs with the Grand Cru village of Avize noted.

Benoît France’s Carte des Vin. This is an entire series covering French wine regions–including a detailed map on La Vallée de la Marne.

Unfortunately, these maps are mostly only available in France. However, I was able to buy several when I lived in the US through Amazon for around $11-13 each. You will still need to pay international shipping. But buying multiples at once helps offset that a little.

Hugh Johnson and Jancis Robinson’s World Atlas of Wine is always a reliable resource. It will list many of the villages and show topographical details. The only negative is that it doesn’t highlight the 17 subregions within Champagne.

There are six in the Vallée de la Marne.

Grande Vallée de la Marne

Vallée de la Marne Rive Droite (Right, or northern, bank of the Marne)

Vallée de la Marne Rive Gauche (Left bank of the river)

Côteaux Sud d’Épernay

Vallée de la Marne Ouest (Western valley)

Terroir de Condé

Across the 103 villages of the Vallée de la Marne, it’s no shock that Pinot Meunier reigns supreme. The grape accounts for nearly 60% of all plantings.

The Marne river meandering by the premier cru village of Hautvillers.

As with many river valleys, frost is always going to be a hazard as cold air sinks and follows the rivers. Compared to larger bodies of waters such as lakes or estuaries, the relatively narrow and low-lying Marne doesn’t moderate the climate as dramatically.

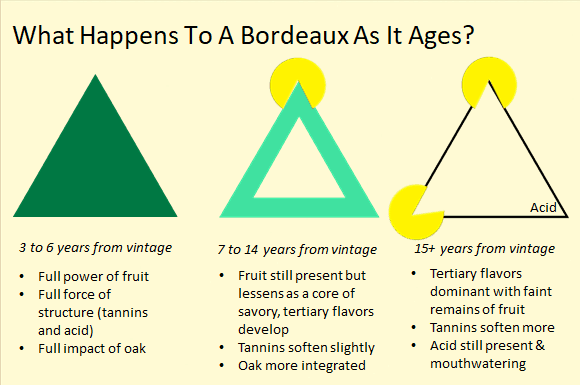

That means that drops in temperature during bud break can be devastating for a vintage. A perfect example of this was the 2012 vintage.

This risk is most severe for Pinot noir. It buds the earliest followed soon after by Chardonnay. Then several days later, Pinot Meunier hits bud break–often missing the worst of the frost.

As we saw with many of the exceptions in the Montagne de Reims, the threat of frost in river valleys tilts the favor towards Meunier. It also helps that the grape is a tad more resistant to botrytis than Pinot noir and Chardonnay. This and other mildews thrive in the damp, humid conditions encouraged by the morning fog following the river.

Finally, while there is limestone throughout the Vallée de la Marne, it’s more marl (mixed with sand and clay) rather than chalk. Pinot noir and Chardonnay can do very well in these kinds of soils. However, Pinot Meunier has shown more affinity for dealing with the combination of cooler soils and a cooler, wetter climate.

But, of course, there are always exceptions–none more prominent than the Grande Vallée de la Marne.

In many ways, the Grande Vallée should be thought of as the southern extension of the Montagne de Reims. Its two Grand Crus, Aÿ and Tours-sur-Marne, share many similarities with its neighbors, Bouzy and Ambonnay.

Along with the “super premier cru” of Mareuil-sur-Aÿ, these south-facing slopes produce powerful Pinot noirs with excellent aging potential. Notable vineyards here include Philipponnat’s Clos des Goisses, Billecart-Salmon’s Clos Saint-Hilaire and Bollinger’s Clos St.-Jacques & Clos Chaudes Terres (used for their Vieilles Vignes Françaises).

Jamie Goode has a fantastic short video (1:55) walking through the two Bollinger vineyards. One thing to notice is that the vines are trained to stakes and propagated by layering.

Compared to most of the Montagne de Reims, the vineyards here are slightly steeper. They’re also at lower altitudes as the land slopes towards the river. However, in contrast to most of the Vallée de la Marne west of Cumières (the unofficial end of the Grande Vallée), the climate is warmer here–tempering some of the frost risks.

Also, the topsoils are thinner with the influence of chalky bedrock more keenly felt. This is particularly true in the eastern premier cru village of Bisseuil, which is planted to majority Chardonnay (66%) and only 6% Pinot Meunier. These grapes go into the cuvées of many notable Champagne producers. Among them, AR Lenoble, Deutz, Mumm and Gonet-Médeville.

Though Chardonnay is mostly a backstage player in the Grande Vallée, the premier cru Dizy (37% Chardonnay) joins Bisseuil as notable exceptions. This is the home turf of Jacquesson with Perrier-Jouët and Roederer also getting grapes from here.

Across the Grande Vallée, Pinot noir reigns supreme.

It accounts for nearly 65% of all the plantings among the 12 villages of the region. Here Pinot Meunier is a distant third with only around 15% of vineyard land devoted to it.

Meunier slowly starts to creep up in importance the further west you go. Here the soils get cooler and clay-rich with more sand. In the premier cru of Champillon, Pinot Meunier accounts for 31% of plantings and is an important source for Moët & Chandon.

Likewise, in its neighbor to the west, Hautvillers (the historical home of Dom Perignon), Meunier also accounts for around a third of vineyards. Of course, Moët & Chandon sees a good chunk of Hautvillers’ grapes along with Veuve Clicquot, Roederer, Jacquesson and Joseph Perrier.

The vlogger Ben Slivka has a 2-minute video of the area taken from a vista point near Champagne G.Tribaut.

Côteaux Sud d’Épernay

Across the river from the Grande Vallée is the city of Epernay. The hills extending south and slightly west make up an interesting transition area between the Vallée de la Marne and Côte des Blancs.

The chalky bedrock is closer to the surface, with far less sand than most of the Vallée de la Marne. However, there is considerably more clay (and less east-facing slopes) in the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay than the Côte des Blancs. The area is slightly dominated by Pinot Meunier (45%), with Chardonnay close behind at 43%. The city of Épernay, itself, is an autre cru with considerable Chardonnay plantings (60%).

There is also quite a bit of rocky–even flinty-soil in the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay. This is particularly true around the premier cru village of Pierry which was the home of the influential monk, Frère Jean Oudart.

Dom Perignon likely spent his career trying to get rid of bubbles. However, his near-contemporary Oudart (who outlived Perignon by almost three decades) actually used liqueur de tirage (sugar and yeast mixture) to make his wines sparkle intentionally.

Except for Pierry, all the villages of the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay are autre crus.

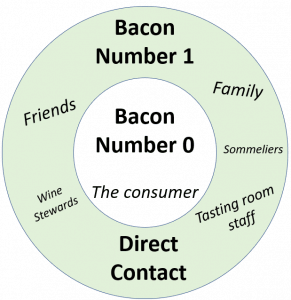

Another geeky cool thing about Laherte Frères’ Les 7 Champagne is that it’s made as a perpetual cuvee in a modified solera system.

However, there are many notable villages, including Chavot-Courcourt–home to one of Champagne’s most exciting wine estates, Laherte Frères.

While the plantings of Chavot-Courcourt are slightly tilted towards Pinot Meunier (51% to 44% Chardonnay), in Laherte Frères’ Les Clos vineyard, all seven Champagne grape varieties are planted. Here Aurélien Laherte uses Pinot blanc, Pinot gris, Arbane and Petit Meslier to blend with the traditional big three to make his Les 7 cuvée. This is another “Must Try” wine for any Champagne lover.

Further south, we get closer to the Côte des Blancs with thinner top soils leading to more chalky influences. Here we encounter a string of villages all paced by Chardonnay–Moslins (58%) Mancy (52%), Morangis (52%) and Monthelon (51%).

Going back towards the northwest, the soils get cooler with more marly-clay. We return to Meunier country in villages such as Saint-Martin-d’Ablois (80% Pinot Meunier) and Moussy (61% PM)–home to the acclaimed Meunier-specialist José Michel & Fils and a significant source of grapes for Deutz.

Vallée de la Marne Rive Droite and Rive Gauche

As we move west, the superlatives of the Vallée de la Marne being Pinot Meunier country becomes gospel. The cold, mostly clay, marl and sandy soils lend themselves considerably to the early-ripening Meunier. Accounting for more than 75% of plantings, it’s only slightly more dominant in the Rive Gauche than the Rive Droite (70%).

Because of its location, there are more north-facing slopes on the left bank of the Rive Gauche. Conversely, the right bank of the Rive Droite has mostly south-facing slopes. This topography plays into the narrative that the Meunier from the Rive Gauche tends to be fresher, with higher acidity. In contrast, those from the Rive Droite are often broader and fruit-forward.

However, there are several valleys and folds along tributaries running into the Marne. This leads to a variety of exposures in each area. But with these tributaries comes more prevalence for damp morning fog. Along these narrow river valleys, the risk of botrytis-bunch rot increases. While Pinot Meunier is slightly less susceptible than Pinot noir and Chardonnay, it’s still a significant problem in the Marne Valley. The 2017 vintage is a good example of that.

Though not about Champagne, the Napa Valley Grape Growers has a great short video (3:30) about botrytis. While desirable for some wines, it usually wreaks havoc in the vineyard.

Since there are few exceptions in these areas, I’ll note some villages worth taking stock of.

Damery (Rive Droite) – Located just west of Cumières, Damery is on the border with the Grande Vallée. With over 400 ha of vines, it’s the largest wine-producing village in the Vallée de la Marne. Planted to 61% Meunier, Damery is an important source for many notable Champagne houses. Among them, AR Lenoble, Billecart-Salmon, Joseph Perrier, Taittinger, Roederer, Bollinger and Pol Roger.

Sainte-Gemme (Rive Droite) – With over 92% Pinot Meunier, this autre cru is one of Krug’s leading sources for the grape.

Mardeuil (Rive Gauche) – With 30% Chardonnay, this village has the highest proportion of the variety in the Rive Gauche. Henriot gets a good chunk of this fruit along with Moët & Chandon.

Festigny (Rive Gauche) – A solitary hill within a warm valley, this village reminds Peter Liem, author of Champagne, of the hill of Corton in Burgundy. While there is more chalk here than typical of the Marne, this area is still thoroughly dominated by Meunier (87%). Festigny is noted for its many old vine vineyards–particularly those of Michel Loriot’s Apollonis estate.

Gary Westby of K & L Wine Merchants visited Loriot in Festigny where he made the video below (1:12).

Vallée de la Marne Rive Ouest and the Terroir de Condé

We wrap up our overview of the Vallée de la Marne by looking at the westernmost vineyards in Champagne. I also include the Terroir de Condé here because it seems like the classification of villages is frequently merged between the two.

Saâcy-sur-Marne (Ouest) – One of only three authorized Champagne villages in the Seine-et-Marne department that borders Paris. In fact, Saâcy-sur-Marne is closer to Disneyland Paris (50km) than it is to Epernay (70km). Going this far west, the soils change–bringing up more chalk. Here, in this left bank village, Chardonnay dominates with 60%.

Connigis (Ouest) – This is the only village in the western Marne Valley where Pinot noir leads the way. It just scrapes by with 45% over Meunier (41%). On the left bank of the river, Connigis used to be considered part of the Terroir de Condé. Today, Moët & Chandon is a significant purchaser of grapes from this autre cru.

Trélou-sur-Marne – Like all of the (current) Terroir de Condé, this village is overwhelmingly planted to Pinot Meunier (72%). However, it’s worth a historical note as being the first place where phylloxera was found in the Marne. This right bank village also helps supply the behemoth 30+ million bottle production of Moët & Chandon.

Kristin Noelle Smith has an 8-part series on YouTube where she focuses on notable producers of Champagne.

In episode three on Moët & Chandon (26:35), Smith touches on the impact of phylloxera in Champagne.

Takeaways

Though the Marne flows westward, the best way to think of the Vallée de la Marne is as a river of Pinot Meunier that changes as you go east. In the west, it truly lives up to the superlative of Meunier-dominance. This is because of the influence of the river and abundance of cold, clay and sand-based soils. But as we go east, and the river widens by the city of Épernay, the story changes considerably.

The part that “forks” north, the Grande Vallée, shares similarities with the southern Montagne de Reims. Here the terroir takes on more of the characteristics of the Pinot noir-dominant Grand Crus of Bouzy and Ambonnay. Whereas the south fork of the Côteaux Sud d’Épernay becomes gradually chalkier. This explains why you see more Chardonnay-dominant villages the closer you get to the Côte des Blancs.

Nailing these two big distinctions (as well as understanding why Meunier thrives in the Marne) is truly dangerous knowledge. Especially for your pocketbook!

So drink up and I’ll see you for part III on the Côte des Blancs!