This is the second part of our Geek Notes review of the GuildSomm podcasts with Ruinart’s chef de cave Frédéric Panaiotis. To catch up on the first segment, check out Geek Notes — The Process of Champagne GuildSomm Podcast.

In that post I also highlight why listening to podcasts is an extremely valuable tool for wine students. But not all podcasts are created equal or are worth your time. There have been many podcasts that I’ve picked up only to unsubscribe after a couple of episodes. Sometimes it is the overall production value that steers me away–noticeable mouth breathing, weird audio jumps between loud voices and whispers, distracting background music, etc. But usually, it is because of a lack of credibility in the content and people producing the podcast.

The world of wine is constantly changing and there is a lot of material to cover. Any podcast that is worth its salt needs to be backed up with solid research and commitment to accuracy.

One of the best wine podcasts, in that regard, is the GuildSomm podcast founded by Master Sommelier Geoff Kruth.

Some Background

Kruth founded GuildSomm in 2009 as a nonprofit that promotes education and development opportunities for sommeliers and other wine professionals. Though many people who aspire to be Master Sommeliers join and utilize the website’s materials, GuildSomm is not a part of the Court Of Master Sommeliers.

Podcasts, videos and recent articles are available to anyone for free on the website. However, access to the forums, study guides, maps, master classes and in-depth training material on topics like blind tasting require membership. For wine industry folks, the fee is $100 a year while for non-industry wine lovers it is $150.

Fun Things I Learned From This Podcast

Ruinart’s non-vintage blanc de blancs and rose.

Like the previous podcast, this episode (44:54) features a highly informative interview with Ruinart’s Frédéric Panaiotis. But the second half is a discussion with the acclaimed grower-producer Rodolphe Péters of Pierre Péters.

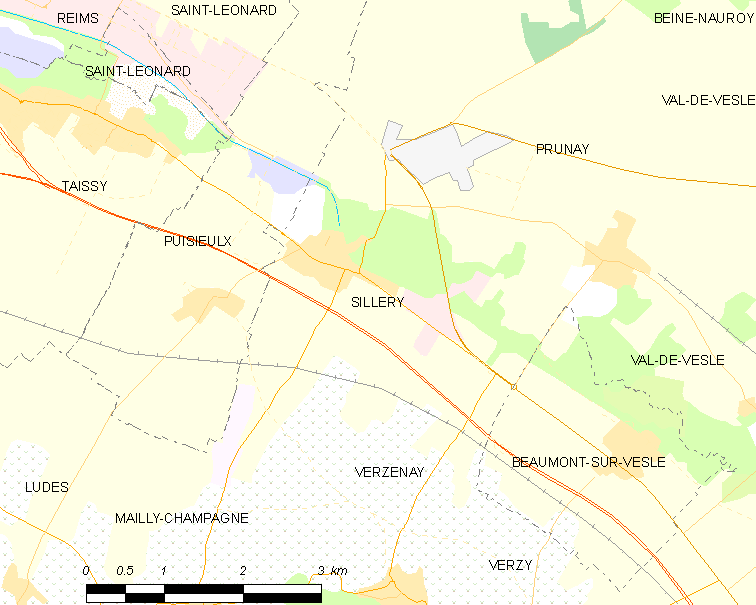

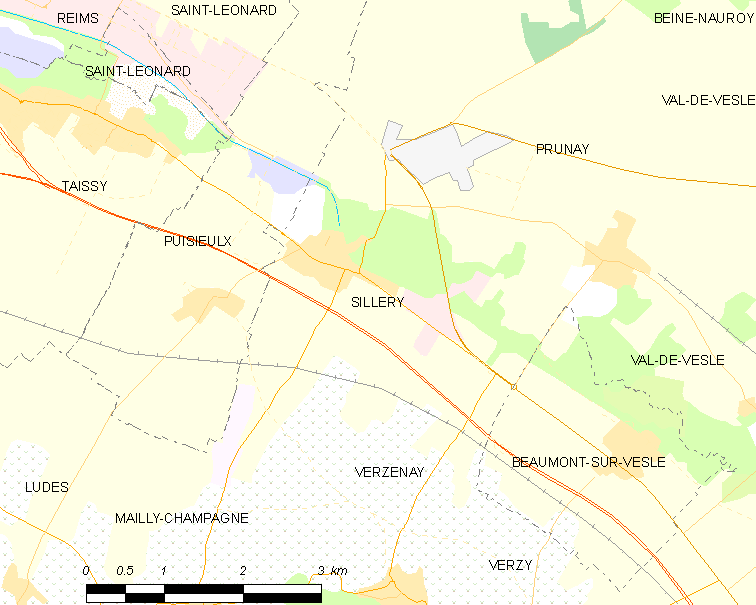

(1:29) The podcast starts with a description of the Montagne de Reims region of Champagne. This area, south of the city of Reims, has a unique horseshoe shape.

The topography creates a diversity of exposures in nearly all orientations (south, east, north, west, etc). This makes it hard to generalize the style of wines from its several villages–including 10 Grand Cru (Ambonnay, Beaumont-sur-Vesle, Bouzy, Louvois, Mailly-Champagne, Puisieulx, Sillery, Tours-sur-Marne, Verzenay and Verzy).

Panaiotis gives a nice overview here but for anyone wanting to really dive deep into this diverse terroir, I very highly recommend Peter Liem’s Champagne, one of my 5 essential books on Champagne.

(2:00) Panaiotis does note, however, that the northern side of the Montagne de Reims (which includes the Grand Cru villages of Mailly, Sillery, Verzy and Verzenay) produces wines with more fresh acidity that have great aging potential.

Chardonnay From the Heart of Pinot-country

The village of Sillery is located southeast of Reims and north of the Grand Crus of Mailly, Verzenay and Verzy.

(2:23) Even though the Montagne de Reims is known for Pinot noir, the eastern villages (mostly premier cru) are esteemed for the quality of their Chardonnay. Panaiotis describes how the gentle eastern exposure of these villages is similar to the Cote d’Or’s east-facing escarpment. Ruinart uses a lot of this fruit for their blanc de blancs Champagne.

(3:49) Sillery is the only Grand Cru of the Montagne de Reims that has more Chardonnay than Pinot noir.

(5:37) Kruth asks Panaiotis how much of Ruinart’s Chardonnay comes from the Montagne de Reims. It is around 30%.

(5:52) Instead of keeping the juice from different villages separate, Ruinart blends the wines regionally. The reason for this is logistics and the need to fill up tanks quickly. As I noted in the last Geek Notes on the process of Champagne, this is a significant divergence in the mindset of small growers versus big houses.

An Overview of Vintages

(8:26) Kruth asks about the recent vintages of Champagne. 2007 was a Chardonnay year while rain took a toll on Pinot noir and Meunier. In contrast, 2008 was more of a Pinot year. 2009 was a warmer year producing more rounder wines. While Panaiotis doesn’t elaborate, I’m curious if he was insinuating that he’s not expecting the 2009s to age as long as other vintages. But the trade-off could be more approach-ability when younger.

(9:36) 2010 is similar to 2007 in being a Chardonnay year. Panaiotis seems high on this year for Ruinart Champagnes. He compares it to 2002 regarding power but with more freshness and expects it to be a benchmark year. However, also like 2007, this was more of a difficult year for the Pinots.

Chardonnay Years vs Pinot Years

Chardonnay harvest in the village of Festigny (an Autre cru) in the Vallée de la Marne.

While it is a bit simplistic to think of years as Chardonnay years or Pinot years, it is a good starting point. Each of the major houses has a distinctive “house style” that tends to lean more on one grape variety or the other. Of course, they are going to try to make the best Champagne they can every year. But it is worthwhile to make a mental note of which years tend to favor a particular house style–especially if you are thinking about splurging for a prestige cuvee.

For instance, other Chardonnay-dominated houses like Ruinart include Perrier-Jouët, Taittinger, Laurent-Perrier and, of course, blanc de blancs specialists like Salon.

Pinot dominated houses include Lanson, Piper-Heidsieck, Mumm, Nicolas Feuillatte, Champagne Mailly, Veuve Clicquot and Moët & Chandon.

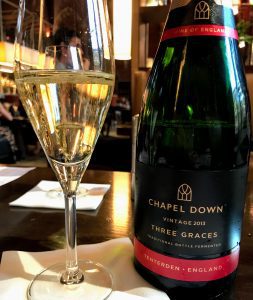

(10:11) 2011 was a tough vintage all around because of rain and botrytis infection. There will likely not be many vintage Champagnes produced. 2012 was a puzzling vintage for Panaiotis because the grapes came in so healthy yet the base wine didn’t live up to his exception to make great a prestige cuvee for Ruinart. He suspects that the year will be better for Pinot dominated producers.

The Wrath of the Drosophila suzukii

The spotted wing Drosophila suzukii wrecked a lot of havoc throughout Europe during the 2014 vintage.

(11:12) 2013 was an easy year with good wines produced. Meanwhile, 2014 had a lot of rot issues caused by an invasion of a Japanese fruit fly that devastated many vineyards (particularly the Pinots). This hit not only Champagne in 2014 but also Germany, Rhône and Burgundy.

However, the fly had issues “seeing” white grapes so the vintage wasn’t as bad for Chardonnay. Still, Panaiotis describes it mostly as a “non-vintage year”.

(12:12) 2015 was a good year but one characterized by drought and low-nitrogen levels in the must. For Ruinart, 2016 was a non-vintage year but Panaiotis notes that some producers like Villamart will be making very good 2016 vintage Champagnes.

(12:35) The 2017 vintage will be interesting because of how mature the grapes were harvested, even though they were picked relatively early. This is a vintage where the impact of global warming will be felt. The year is tilting towards a Chardonnay year (with the Pinots having some rot issues) but will be good for non-vintages.

The Importance of Primary Fermentation

Temperature control during primary fermentation is vitally important in maintaining freshness in Champagne. Here in one of the fermenting rooms of Moët & Chandon each tank is outfitted with a cooling jacket.

(14:10) The conversation switches to fermentation. There is a little overlap with the last podcast in the discussion of things like reductive winemaking.

(17:29) Kruth gives a great analogy of how the effects of the first fermentation get amplified in the secondary fermentation of Champagne. This is a really important point to understand because so often this fermentation gets overlooked because it isn’t the step that produces the “magic” of the bubbles. Yet, a Champagne is only as good as its base ingredient–the vin clair.

(18:13) The reasoning above is why Panaiotis is not a fan of using oak in the first fermentation at Ruinart. However, for other producers like Krug, the “amplification” of those flavors is a house style.

(19:24) One unique thing that Panaiotis mentions in his parting comment is that for the 2010 vintage, Ruinart switched to sealing the wine for the secondary fermentation with cork instead of the traditional crown cap. This is an exciting trend that is getting a lot of attention of late. The idea is that cork allows for better interaction with oxygen and the yeast but there seem to be other benefits as well–including more reductive flavors (!?) Certainly something I want to investigate more.

Interview With Rodolphe Péters of Pierre Péters

The chalky limestone of Champagne A fascinating produced at the same time as the White Cliff of Dover.

(20:50) As the interview switches to Peters, the focus shifts to the terroir of the Côte des Blancs. The origins of the region’s soils are similar to the Montagne de Reims–the ancient sea that birthed the Paris Basin as well as the White Cliffs of Dover.

However, the biggest difference between the two regions is the depth of the topsoil with the soil being much thinner in the Côte des Blancs. This is one of the reasons why Chardonnay is favored here since it can deal with shallow top soils easier than Pinot noir.

(22:59) Another comparison between the Côte des Blancs and the Cote d’Or with its north-south band of vineyards that face east. But here Peters points out the favor-ability of east-facing slopes–the gentle early morning heat of the sun instead of the harsher late afternoon heat that hits others exposures.

This is helpful in slowing down the maturation of Chardonnay which can risk losing elegance and flavor if it ripens too much, too quickly.

(23:54) Echoing again some of the sentiments of Frédéric Panaiotis in the first half, Peters calls out the specialness of Chardonnay from the eastern villages of the Montagne de Reims–particularly the Premier Cru villages of Trépail and Villers-Marmery.

The links to the villages above go to one of my favorite blogs on Champagnes. Each profile also includes a list of growers who produce Champagnes from these villages. These will be high on my list of Champagnes to seek out.

The Four Seasons of the Côte des Blancs

(24:21) Kruth asks for an overview of the different villages of the Côte des Blancs. Peters responds with a very poetic comparison of the personality of the main villages to the four seasons. Le Mesnil-sur-Oger is winter, producing tight Champagnes that can be austere in their youth. This is caused by, in Peters’ opinion, the soft and dry chalk that accentuates the wine’s sharp minerality.

The Grand Cru village of Oger is on flatter land and at a lower altitude than neighboring Le Mesnil-sur-Oger.

While Oger has the same soil profile as Le Mesnil, it is a little flatter and lower in altitude. This creates an amphitheater that warms up the micro-climate of the village, producing softer and rounder wines. Peters equates the style of wine from here to spring with an elegant and feminine character.

Avize is also lower altitude with the best sites located on flat terrain. It has a little deeper topsoil with some clay mixed with the chalk. This is unique compared to the other Côte des Blancs villages because it has a higher concentration of organic material in the soil. This produces a richer, juicer more citrus-style of Chardonnay that Peters equate to summer.

Vineyards in Cramant tend to have an “oilier” chalk that produces creamier style Champagnes.

Cramant is a little higher than Avize in altitude with an “oilier” style of chalk as opposed to the soft and dry chalk of Le Mesnil. This lends itself towards creamier and more approachable Champagnes. Along with the hazelnut and sweet baking spices that they tend to produce, this profile reminds Peters of autumn.

Viticulture and Climate Change

(29:45) Kruth asks about what differences in viticulture that are seen in the Côte des Blancs compared to other regions of Champagne. Peters notes that his personal approach is a little different than his neighbors. One of his priorities is to minimize compaction of the thin topsoil by limiting the amount of disturbance it sees.

For instance, he cultivates grasses between his vines but doesn’t plow it in. The one exception is in Avize, with its deeper topsoil, which can take some light plowing. However, he is also mindful of the character of a vintage with rainier years sometimes requiring a different approach.

Adapting to Change

While Chardonnay has adjusted to rising temperature, riper Pinot Meunier grapes can create problems with tighter clusters that are more prone to botrytis.

(31:45) Peters notes that Chardonnay growers in the Côte des Blancs have been relatively lucky with a string of good quality and easy vintages. Meanwhile, Pinot producers (particularly Meunier) have had to be on their toes a lot more with the weather change.

One of the challenges for Pinot Meunier that Peters highlights is that the warmer weather is producing bigger, riper berries. While this might seem beneficial on the surface, the stems are not getting any bigger. Therefore, the Pinot Meunier clusters are getting tighter and more compact which increases the risk of botrytis rot, especially in rainy vintages.

(33:09) Chalk is a winemaker’s best friend because of how well it regulates the climate–especially excessive water during rainier vintages. But it also retains water well during drought years. Likewise, the soil is able to deal with hot vintages by absorbing heat and then slowly releasing it later in the night so that the vine is not overwhelmed.

(33:40) Peters notes that over the years, he has seen the major houses gradually increasing the amount of Chardonnay they use due to the grape’s ability to better weather climate change.

A Contrast of Vintages

(34:08) Kruth asks for Peters thoughts on particular vintages. He highlights a few that he thinks are interesting–2013 and 2017.

The 2013 vintage was a long growing season with 104 days of maturation. This allowed the grapes to get perfectly ripe without being excessively mature. In contrast, 2017 was very hot which caused a spike in sugars. Peters noted that growers had to start picking their grapes after 87 days to avoid high alcohol.

However, Peters feels that many of these early harvesters didn’t taste their grapes with the resulting wines still having unripe flavors. He waited till 91 days to get some more maturity. He feels that 2017 is the first vintage that the Champenois really had to face the reality of climate change.

Grand Marque vs Grower

Paul Bara, one of the first grower producers to gain traction in the US.

(37:35) The conversation moves to the general impression of grower-producers, especially in the sommelier community. Kruth wonders if it has now become a marketing wedge like Red States vs Blue States, Grand Marque vs. Grower, etc. He particularly calls out sommeliers who only feature grower Champagnes on their wine lists.

Peters response gives some interesting food for thought and is well worth a listen. He does see benefits of the big houses but notes they have some issues. While grower Champagne answer some of those issues, Peters is not a fan of the idea that merely because something is a grower that it must be good.

(40:45) A really interesting discussion follows Kruth describing the “trick of oxidation” that he feels that some growers utilized to make up for the lack of aging and use of reserve wines. He contrasts this with the long, slow reductive aging of many great Champagnes. This is particularly fascinating in the context of Chardonnay-dominant producers because of how much affinity Chardonnay has for reductive winemaking and how awry it can get without a careful hand if treated oxidatively.

A very thought-provoking conversation to end the podcast on.