In 2016, I dipped my toes into exploring the strange trend of wine aged in whiskey barrels with my original Whiskey and Wine post.

In 2016, I dipped my toes into exploring the strange trend of wine aged in whiskey barrels with my original Whiskey and Wine post.

In that post, I did a blind tasting featuring 3 barrel aged wines and one regular red wine ringer thrown in. While I thought this fad would quickly fade, it looks like it has only picked up steam with new entries on the market.

I decided to investigate a little more with another blind tasting of as many different barrel aged wines that I could find. (Results below)

I got bottles of the Apothic Inferno, Robert Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon and Barrelhouse Red featured in the last blind tasting as well as new bottlings from Mondavi of a bourbon barrel aged Chardonnay (I’m not kidding) and a Cabernet Sauvignon from Barrelhouse. I found further examples from Cooper & Thief, 1000 Stories, Big Six Wines, Stave & Steel and Paso Ranches. For a twist, I also added the 19 Crimes The Uprising that was aged in rum barrels.

I tried to find bottles of The Federalist’s Bourbon barrel aged Zinfandel, Jacob’s Creek Double Barrel Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz and 1000 Stories “half batch” Petite Sirah but to no avail.

So What’s The Deal?

Why are so many producers jumping on this bandwagon?

On Twitter, wine and lifestyle blogger Duane Pemberton (@Winefoot) had an interesting take.

A similar sentiment was shared on Facebook from one of my winemaking friends, Alan, who noted that the charcoal from the heavy toast of the bourbon barrels could function as a fining agent for wines with quality issues like bad odors.

Now considering that many of the mega-corporations behind these wines like Gallo (Apothic), Constellation Brands (Mondavi & Cooper & Thief), The Wine Group (Stave & Steel) and Concha y Toro/Fetzer (1000 Stories) process millions of tons of grapes for huge portfolios of brands, this actually makes brilliant business sense.

Even in the very best of vintages, you are always going to have some fruit that is less than stellar–often from massively over-cropped vineyards that aren’t planted in ideal terroir. Rather than funnel that fruit to some of your discount brands like Gallo’s Barefoot, Constellation’s Vendange and The Wine Group’s Almaden, you can put these wines in a whiskey barrel for a couple of months and charge a $5-10 premium–or in the case of Cooper & Thief, $30 a bottle!

Trying to Keep An Open Mind

Bourbon Standards

In this tasting, I wanted to explore how much of the whiskey barrel influence is noticeable in the wine. In the last blind tasting, one of the things that jumped out for me is that the Mondavi Cab and Barrelhouse red didn’t come across as “Whiskey-like” and were drinkable just fine as bold red wines. Meanwhile, the Apothic Inferno did scream WHISKEY but it came across more like a painful screech.

To facilitate that exploration, I poured some examples of “Bourbon Standards” that the tasting panel could smell for reference (and drink after the tasting if needed!). My Bourbon Standards were:

Larceny — From Heaven Hill Distillery. A “fruity sweet” Bourbon with noticeable oak spice.

Jim Beam — Old standard from Beam-Suntory. A light Bourbon with floral and spice notes.

Two Stars — A wheated Bourbon from Sazerac. It’s kind of like if Buffalo Trace and Maker’s Mark had a baby, this would be it. Caramel and spice with honey and fruit.

Bulleit — Made now at Four Roses Distillery. Sweet vanilla and citrus.

The Wines

Apothic Inferno & Cooper & Thief

Apothic Inferno ($13)

Made by Gallo. Unknown red blend. This wine is unique in that it only spent 60 days in whiskey barrels (as opposed to bourbon barrels) while most of the other reds spent 90 days. 15.9% ABV

Cooper & Thief ($30)

Made by Constellation under the helm of Jeff Kasavan, the former director of winemaking for Vendange. I did appreciate that this was the only red blend that gave its blend composition with 38% Merlot, 37% Syrah, 11% Zinfandel, 7% Petite Sirah, 4% Cabernet Sauvignon and 3% “other red grapes.” The wine was aged for 90 days and had the highest ABV of all the wines tasted with 17%. This wine was also unique in that it was from the 2014 vintage while all the other reds (except for the 19 Crimes) were from the 2015 vintage.

Barrelhouse ($13-14)

Made by Bruce and Kim Cunningham of AW Direct. A Cabernet Sauvignon and unknown Red Blend aged 90 days in bourbon barrels. Both of these wines were unique in that they had the lowest alcohol levels in the tasting with only 13.2% while most of the other wines were over 15%.

Big Six ($15 each)

Made by god knows who. The back label says it is from King City, California which means that it could be a Constellation brand or it could be made at a custom crush facility like The Monterey Wine Company. They offer a Cabernet Sauvignon, unknown Red Blend and Zinfandel aged 90 days in bourbon barrels with ABVs ranging from 15.1% (Red blend) to 15.5% (Zinfandel).

Paso Ranches Zinfandel ($20)

Made by Ginnie Lambrix at Truett Hurst. While most wines were labeled as multi-regional “California,” this wine is sourced from the more limited Paso Robles AVA. Aged 90 days with a 16.8% ABV.

Robert Mondavi ($12 each)

Made by Constellation Brands. A Cabernet Sauvignon aged 90 days and a Chardonnay aged for 60 days with both wines having an ABV of 14.5%. Like the Paso Ranches, these wines were sourced from the more limited Monterrey County region.

Stave & Steel Cabernet Sauvignon ($17)

Made by The Wine Group. This wine was unique in that it was aged the longest of all the wines with four months. Like the Barrelhouse, this wine had more moderate alcohol of 13.5%

Got only crickets from them on Twitter as well.

1000 Stories Zinfandel ($17)

Made by Fetzer which is owned by Concha y Toro. This was one of the first wineries in the US to release a bourbon barrel aged wine back in 2014 with winemaker Bob Blue claiming that he’s been aging wine in old whiskey barrels since the 1980s. This was the only wine that I could not figure out how long it was aged with the bottle or website giving no indication. The ABV was 15.6%

19 Crimes ($8)

Made by Treasury Estates with wine sourced from SE Australia. Unknown red blend that was aged 30 days in rum barrels with 15% ABV. This was the youngest wine featured in the tasting coming from the 2016 vintage.

The Blind Tasting

To be as objective as possible, especially with some of the wines like the Cooper & Thief having very distinctive bottles, I brown bagged the wines and had my wife pour the wines in another room. We also “splash decanted” all the wines (except for the Chardonnay) to clear off any reductive notes.

After trying the Chardonnay non-blind, my wife would randomly select an unmarked bag, label it A through L and poured the wines in 6 flights of 2 wines each. We then evaluated the wines and gave each a score on a scale of 1-10. Below is a summary of some of our notes, scores and rankings with the reveal to follow. My friend Pete contributed the colorful “personification” of the wines in his tasting notes. The wine price ranges are from my notes.

To keep our palates as fresh as possible we had plenty of water and crackers throughout the tasting. And boy did our poor little spit bucket get a workout, needing to be emptied after every other flight. But even with spitting, it was clear that we were absorbing some of the high alcohol levels. After six reds, we also paused for a break to refresh our palates with some sparkling wine.

Mondavi Chardonnay (Scores 4, 7, 6, 5.5, 4 = 26.5 for 7th place)

Vanilla, butterscotch, canned cream corn & tropical fruit like warm pineapple. More rum barrel influence than bourbon. Drinks like something in the $7-8 range

Wine A (Scores 6, 7.5, 6, 7, 6 = 32.5 for 3rd place)

Baby powder and baking spice. Noticeable Mega-Purple influence. Maybe a Zin or Petite Sirah. Minimal oak influence. Some burnt char. Kind of like the girl you met at the carnival, take for a ride but don’t buy her cotton candy. Drinks like something in the $10-12 range.

Many wines were very dark and opaque.

Wine B (Scores 2, 3, 4, 2, 2 = 13 for 11th place)

Very sweet. Lots of vanilla. Noticeable oak spice and barrel influence. Little rubber. More rye whiskey than bourbon. Taste like oxidize plum wine. Very bitter and diesel fuelish. Reminds me of a Neil Diamond groupie. Drinks like something in the $7-8 range.

Wine C (Scores 7, 7, 7, 7, 3 = 31 for 5th place)

Smells like a ruby port or Valpolicella ripasso. Some wintergreen mint and spice. Cherry and toasted marshmallow. Noticeable barrel influence. Reminds me of Karen from Mean Girls. Drinks like something in the $10-12 range.

Wine D (Scores 3, 4.5, 5, 2, 2 = 16.5 for 10th place)

Very sweet, almost syrupy. Burnt creme brulee. Burnt rubber. Toasted coconut. Rum soaked cherries. The color is like Hot Topic purple hair dye. Super short finish which is a godsend. If this wine was a person, her name would be Chauncey. Drinks like something in the $5-6 range.

Wine E (Scores 6, 7, 6, 8, 7 = 34 for 2nd place)

Raspberry and vanilla. Graham cracker crust. Not as sweet as others. Very potpourri and floral. Really nice nose! Smells like the Jim Beam. Little Shetland pony earthiness. High heat and noticeable alcohol. Reminds me of the guy who is really ugly but you like him anyways. Drinks like something in the $14-16 range.

Wine F (Scores 3.5, 5.5, 4, 5, 5 = 22 for 8th place)

Toasted marshmallows. Noticeably tannic like a Cab. Raspberry and black currants. Not much barrel influence. This wine seems very robotic. Drinks like something in the $12-14 range.

That spit bucket rarely left my side during this tasting.

Wine G (Scores 6.5, 7, 3, 6.5, 6 = 27 for 6th place)

Tons of baking spice. Very noticeable oak. Reminds me of a Paso Zin. Lots of black pepper–makes my nose itch. Slightly sweet vanilla. Most complex nose so far. Would be a delicious wine if it wasn’t so sweet. Reminds me of a Great Depression-era dad. Drinks like a $14-16 wine.

Wine H (Scores 2, 3, 3, 1, 2 = 11 for 13th last place)

Burnt rubber tires. Smells very boozy. Fuel. Taste like really bad Seagram’s 7. Cheap plastic and char like someone set knockoff Crocs shoes on fire. Reminds me of Peter Griffin. Drinks like something in the $7-8 range.

Wine I (Scores 7.5, 6.5, 7, 8, 7 = 36 for 1st place)

Dark fruit and pepper spice. Turkish fig. Juicy acidity. Not as sweet. Round mouthfeel and very smooth. Creamy like butterscotch. Not much barrel influence. Reminds me of a sociopath that you don’t know if they want to cuddle with you or cut your throat. Drinks like something in the $14-16 range.

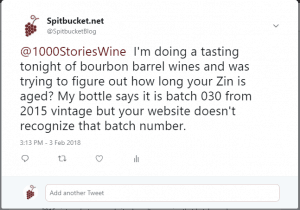

Wine J (Scores 4, 4, 3, 4, 3 = 19 for 9th place)

Marshmallow fluff. Caramel. Very sweet. Smells like a crappy Manhattan with a cherry. Seems like a boozy Zin. Not horrible but still bad. Not much barrel influence at all. Reminds me of children. Drinks like a $10-12 wine.

Wine K (Scores 7, 6.5, 8, 4, 6 = 31.5 for 4th place)

Big & rich. Juicy cherries. Sweet but not overly so. Little pepper spice. Very easy drinking. Something I would actually drink. Not much barrel influence. Makes me think of the “I’ve got a Moon Ma” guy. (author’s note: I have no idea what Pete is referring to here. This is my best guess.) Drinks like a $10-12 wine.

Wine L (Scores 1, 4, 2, 4, 1 = 12 for 12th place)

Stewed plums and burnt rubber. Lots of tannins and acid. The worst thing I’ve had in my mouth all week. Pretty horrible. Long, unpleasant finish. Reminds me of Sloth from The Goonies. Drinks like a $10-12 wine.

The Reveal

After tallying up the scores, we revealed the wines. In order from best to worst tasting of the barrel aged wines:

The closeness in style and rankings of the 3 Big Six wines were surprising.

1st Place: Barrelhouse Red (Bag I)

2nd Place: Stave & Steel Cabernet Sauvignon (Bag E)

3rd Place: Mondavi Cabernet Sauvignon (Bag A)

4th Place: Big Six Zinfandel (Bag K)

Big Six Cabernet Sauvignon (Bag C)

Big Six Red Blend (Bag G)

Mondavi Chardonnay (non-blind)

Barrelhouse Cabernet Sauvignon (Bag F)

19 Crimes The Uprising (Bag J)

Cooper & Thief (Bag D)

Paso Ranches Zinfandel (Bag B)

1000 Stories Zinfandel (Bag L)

Last Place: Apothic Inferno (Bag H)

Final Thoughts

One clear trend that jumped out was that the top three wines had moderate alcohol (13.2% with the Barrelhouse to 14.5% with the Mondavi). Overall these wines tasted better balance and had the least amount of the off-putting burnt rubber and diesel fuel note which tended to come out in the worst performing wines like the Apothic Inferno (15.9%), Cooper & Thief (17%), 1000 Stories Zin (15.6%) and Paso Ranches Zin (16.8%).

Another trend that emerged that was similar to the previous tasting (which had the Barrelhouse Red and Mondavi Cab also doing very well) is that the most enjoyable wines were the ones with the least obvious whiskey barrel influence. This was true even with the 2nd place finish of the Stave & Steel that was the wine that spent the most time in the barrel at four months. That is a testament to the skill of the winemaker where the whiskey barrel is used as a supporting character to add some nuance of spice and vanilla instead of taking over the show.

Comparing the four months aged Stave & Steel to the two months aged Apothic Inferno is rather startling because even with a shorter amount of barrel time the Apothic seemed to absorb the worst characteristics from the whiskey barrel with the burnt rubber and plastic. The 19 Crimes that only spent 30 days in rum barrels didn’t show much barrel influence at all.

It also appears that, in general, Cabernet Sauvignon takes better to the barrel aging compared to Zinfandel. However, the Big Six Zinfandel did reasonably well to earn a 4th place finish. The most challenging task for winemakers is to try and reign in the sweetness. Several of these wines had notes like Wine G (the Big Six red blend that is probably Zin dominant) that they would be decent wines if they were just a bit less sweet.

One last take away (which is true of most wines) is that price is not an indicator of quality.

Three of the worst performing wines were among the four most expensive with the $17 1000 Stories Zin, $20 Paso Ranches Zin and the $30 Cooper & Thief. The Cooper & Thief tasted so cheap that I pegged it as a $5-6 wine. It is apparent that you are paying for the unique bottle and fancy website with this wine.

Only the $17 Stave & Steel that came in 2nd held its own in the tasting to merit its price. However, the Barrelhouse Red at $13 and Mondavi Cab at $12 offer better value.

It’s clear that this trend is not going away anytime soon. If you’re curious, these wines are worth exploring but beware that they vary considerably in style, alcohol and sweetness. Grab a few bottles and form your own opinion.

But take my advice and have some good ole fashion real whiskey on standby. Those “bourbon standards” certainly came in handy after the tasting.

A few quick thoughts on the 2017 Calcareous Vin Gris Cuvée from Paso Robles.

A few quick thoughts on the 2017 Calcareous Vin Gris Cuvée from Paso Robles.

A few thoughts on

A few thoughts on

In 2016, I dipped my toes into exploring the strange trend of wine aged in whiskey barrels with my

In 2016, I dipped my toes into exploring the strange trend of wine aged in whiskey barrels with my