Going to need more than 60 Seconds to geek out about the 2013 Otis Kenyon Roussanne from Lawrence Vineyards in the Columbia Valley AVA.

Going to need more than 60 Seconds to geek out about the 2013 Otis Kenyon Roussanne from Lawrence Vineyards in the Columbia Valley AVA.

The Background

Otis Kenyon was founded in 2004 by Steve Kenyon who still runs the winery today with his daughter, Muriel.

The winery’s name comes four generations of Otis Kenyons with the original John Otis Kenyon, a dentist by training, being a notorious figure in Walla Walla for burning down a competitor’s office when the later starting stealing half of Kenyon’s clients.

The labels of Otis Kenyon wines pay tribute to this family history in a playful manner with a silhouette of the original Otis Kenyon with singed edges as well as a red wine blend, Matchless, featuring an open matchbook on the label. The winery’s “business cards” are also matchbooks filled with actual matches.

Along with sourcing fruit from throughout the Columbia Valley, Otis Kenyon has an estate vineyard, Stellar Vineyard, located in the Rocks District of Milton-Freewater on the Oregon side of Walla Walla.

The wines are made by Dave Stephenson, who founded his eponymous Stephenson Cellars in 2001. Prior to working at Otis Kenyon, Stephenson started his career at Waterbrook and today consults for several boutique wineries.

Around 247 cases of the 2013 Otis Kenyon Roussanne were made.

The Vineyard

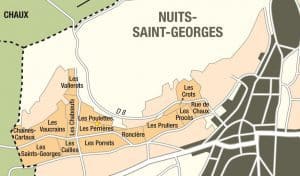

Map showing the proposed Royal Slope AVA (in yellow) where Lawrence Vineyards are located. Prepared by Richard Rupp of Palouse Geospatial.

The Lawrence Vineyards are located on the Frenchman Hills of the Royal Slope of the Columbia Valley basin and includes six named sites–Corfu Crossing (first planted in 2003), Scarline (2003), La Reyna Blanca (2010), Laura Lee (2008), Solaksen (2013) and Thunderstone (2015). The Lawrence family also manages the nearby Boneyard Vineyard that includes five acres of Syrah. All the Lawrence Vineyards are sustainably farmed.

While managing 330+ acres of plantings the Lawrence family also own Gård Vintners which produces around 6000 cases a year sourced from their estate grown fruit and made by Aryn Morell. Together with Morell they also produce Morell-Lawrence Wines (M & L).

The Roussanne used by Otis Kenyon cames from 2007 plantings of the Tablas Creek clone in Corfu Crossing which sits on a south facing slope at an elevation that ranges from 1,365-1,675 ft. The soils here are a mixture of silt and sandy loam on a bedrock of fractured basalt.

Riesling sourced from Lawrence Vineyards has been used in some of the state’s most highly acclaimed Riesling wines.

In addition to Otis Kenyon, M & L and Gård, other wineries that source fruit from Lawrence includes Latta Wines, Southard Winery, Cairdeas, Armstrong Family, Matthews Winery, Pend d’Oreille as well as Chateau Ste. Michelle for their top-end Riesling Eroica.

Other varieties that the Lawrence Vineyards farm include Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grenache, Malbec, Merlot, Mouvedre, Pinot noir, Chardonnay, Pinot gris, Sauvignon blanc and Viognier.

The (future) AVA of the Royal Slope

The proposed Royal Slope AVA was formerly delineated and submitted for AVA approval in early 2017. It includes the south facing slopes around Royal City located between the established AVAS of the Ancient Lakes and Wahluke Slope. Within the AVA is a sub-region of the Frenchmen Hills. The lead petitioner for the AVA was geologist Alan Busacca, former professor at Washington State University and Walla Walla Community College who also wrote the successful petitions for the Wahluke Slope, Lake Chelan and Lewis-Clark Valley AVAs.

The topography can range from relatively gentle to fairly steeper slopes of up to 22 degrees in the Frenchmen Hills region. The soils are fairly uniformed in their mixture of sandy and silty loam river deposits covering layers of fractured basalt left over from a period of intense volcanic activity during the Miocene Epoch. These soils are very high in calcium carbonate which may contribute to the strong minerality that wines from the Royal Slope tend to exhibit.

Throughout the growing season the region sees heat units (growing degree days or GDD) ranging from 2700 GDD to over 3000 GDD making it one of the warmest wine regions in the state. However the areas bordering the Ancient Lakes AVA to the northeast can be considerably cooler.

Charles Smith’s highly acclaimed K Vintners Royal City Syrah is sourced from the Stoneridge Vineyard in the proposed Royal Slope AVA.

Elevations range from 900 feet to upwards of 1700 feet with the higher elevation sites seeing much more diurnal temperature variation from the daytime highs to very cool temperatures at night which maintains acidity and keeps the vine from shutting down due to heat stress.

The proposed AVA contains 156,389 acres of which around 1400 have already been planted. Other notable vineyards in this proposed AVA includes Novelty Hill Winery’s estate vineyard Stillwater Creek, Frenchmen Hills Vineyard and Stoneridge

The Grape

Jancis Robinson, Julia Harding and José Vouillamoz note in Wine Grapes that the first recorded documentation of Roussanne occurred in 1781 describing its use in the white wines of Hermitage. The name Roussanne is believed to be derived from the French term roux and could refer to the russet golden-red color of the grapes’ skins after veraison.

DNA analysis shows that there is a likely parent-offspring relationship with Marsanne but it is not yet known which variety is the parent and which is the offspring.

The reddish bronze hue that Roussanne grapes get after veraison likely contributes to the grape’s name.

In the northern Rhône regions of St. Joseph, Hermitage and Crozes-Hermitage, Roussanne adds acidity, richness and minerality when paired with Marsanne. It can also be used in the sparkling Northern Rhone wines of St. Peray. As a varietal it can have a characteristic floral and herbal verbena tea note.

Unlike Marsanne and Viognier, Roussanne is a permitted white grape variety in the red and white wines of Châteauneuf-du-Pape where today it makes up around 6% of the commune’s plantings as the third most popular white grape behind Grenache blanc and Clairette.

From a low point of 54 ha (133 acres) in 1968 plantings of Roussanne steadily grew throughout the late 20th century to 1074 ha (2654 acres) by 2006. Outside of the Rhone, the grape can be found in the Savoie region where it is known as Bergeron and is the sole variety in the wines of Chignin-Bergeron. In the Languedoc-Roussillon it is often blended with Chardonnay, Bourboulenc and Vermentino as well as Grenache blanc and Marsanne.

Roussanne is a late-ripening variety that is very prone to powdery mildew, botrytis and shutting down from excessive heat stress towards the end of the growing season.

Even in ideal conditions, Roussanne can be a troublesome producer in the vineyard with uneven yields often caused by coulure (also known as “shattering”) when the embryonic grape clusters don’t properly pollinate during fruit set after flowering. A significant cause of this is poor management by the vine of its carbohydrate reserves which the vine begins storing for the next year after the harvest of the previous vintage. Other factors at play can include nutrient deficiencies in the soil–particularly of boron and zinc with the later often being exacerbated in high pH soils.

During fruit set (shown here with Merlot), flowers that weren’t pollinated will “shatter” and not develop into full berries. This creates uneven yields with clusters having a mix of fully formed and “shot” berries. Roussanne is particularly susceptible to this condition.

Other varieties that are similarly susceptible to coulure include Grenache, Malbec, Merlot, Muscat Ottonel and Gewürztraminer.

A Case of Mistaken Identity

Prior to phylloxera, Roussanne was relatively well-established in California in the 19th century with plantings in Napa, Sonoma and Santa Clara where it was often blended with Petite Sirah. However, following phylloxera and Prohibition in the 20th century, most all Roussanne vineyards were uprooted.

In the 1980s and early 1990s, producers in California began experimenting again with the variety. In 1994, Chuck Wagner of Caymus Vineyards in Napa purchased 6400 Roussanne vines for his Mer Soleil project. The vines he purchased came from Sonoma Grapevines owned by the Kunde family who originally sourced their cuttings from a vineyard owned by Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon (who did not know that Kunde was going to commercially propagate them). The Bonny Doon cuttings came from a visiting Châteauneuf-du-Pape winemaker.

Many plantings of Roussanne in California in the 1980s and 1990s turned out to be Viognier (pictured).

Four years later a visiting viticulturalist identified the plantings in the Mer Soleil vineyard not as Roussanne but rather as Viognier–an identification that was later confirmed by DNA testing at UC-Davis. The discovery unleashed a cascading effect of lawsuits and countersuits from various parties involved as well as a hunt for true Roussanne plantings in California.

Tablas Creek Winery in Paso Robles began importing their Roussanne cuttings directly from their sister-property, Château de Beaucastel, in Châteauneuf-du-Pape in 1989. Additionally, John Alban began sourcing authentic Roussanne cuttings in 1991 with nearly all of the 323 acres of Roussanne vines in California (as of 2017) now being descendant from the Tablas and Alban vines.

Roussanne in Washington

Paul Gregutt notes in Washington Wines and Wineries that Roussanne in Washington “… can taste like a real fruit salad mix, everything from apples, citrus and lime to peaches, honey and cream.”

The grape was pioneered in Washington by Doug McCrea, the state’s original Rhone Ranger, of McCrea Cellars and Cameron Fries of White Heron Cellars in the 1990s. While varietal examples can be found, the grape is mostly used as a blending component in Rhone-style blends with Grenache blanc, Viognier and Marsanne.

Along with Doug McCrea of McCrea Cellars, Cameron Fries of White Heron Cellars (pictured) helped pioneer Roussanne in Washington State.

By 2017, there were 71 acres of Roussanne planted in Washington.

In addition to the plantings of Lawrence Vineyard, there are notable acreages of Roussanne on Red Mountain at Ciel du Cheval Vineyard, Stillwater Creek, Boushey Vineyard in the Yakima Valley and at Alder Ridge, Destiny Ridge and Wallula Vineyard in the Horse Heaven Hills.

The Wine

Medium intensity nose–tree fruits like spiced pear and apricot with a citrus grassy component that could be verbena.

On the palate the wine is very full-bodied and weighty with almost an oily texture. The spiced pear notes definitely come through with that herbal citrus tinge. Medium-plus acidity is still giving the wine freshness and balancing the weight. The moderate length finish ends on the pear and herbal notes.

The Verdict

I’m usually skeptical about how well many domestic white wines age but this 2013 Otis Kenyon Roussanne is holding on quite well for a 4+ year old white. The acidity seems to be the key and is a helpful balance to the full-bodied fruit.

The big weight and texture of this wine is reminiscent of a lightly oak Chardonnay with no malolactic and would serve as a good change of a pace for not only a Chardonnay drinker but also a red wine fan who is craving something very food friendly to go with heavier cream sauces, pork and poultry dishes.

At $25-30, this wine offers a fair amount of complexity and is definitely worth trying.

We’re back after a vacation to take the nieces and nephew to the happiest place on Earth. Unfortunately, we didn’t get a chance to play

We’re back after a vacation to take the nieces and nephew to the happiest place on Earth. Unfortunately, we didn’t get a chance to play

Going to need

Going to need

Summer’s coming which for me brings visions of lounging in the sun with a nice glass of rosé and something geeky to read.

Summer’s coming which for me brings visions of lounging in the sun with a nice glass of rosé and something geeky to read.

As promised in my summary post about

As promised in my summary post about

Continuing our celebration of the oddly named

Continuing our celebration of the oddly named

Going to need more than

Going to need more than