Be sure to check out Part II on the Vallée de la Marne and Part III on the Côte des Blancs.

I want to do something a little similar to my post on the 8 Myths about the Sherry Solera System that even Wine Geeks Believe. Rather than myths per se, we’re going to tackle the “Butter Knife Knowledge” that a lot of folks have about Champagne.

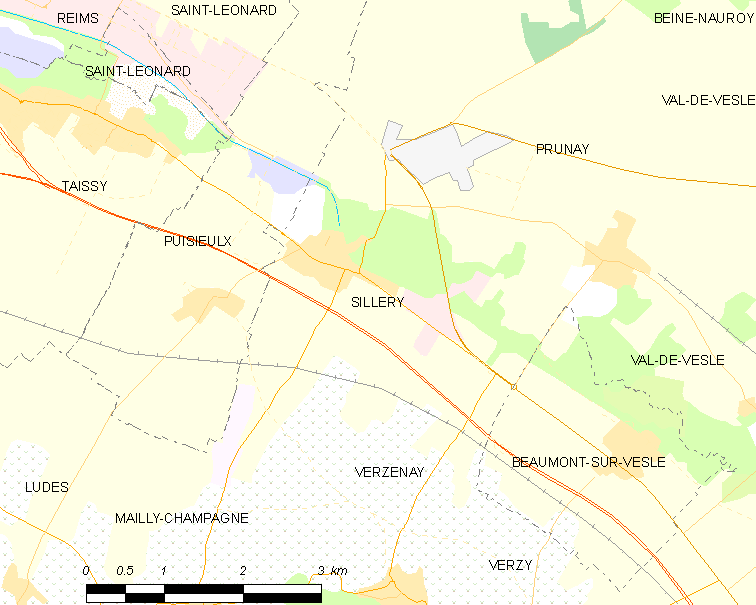

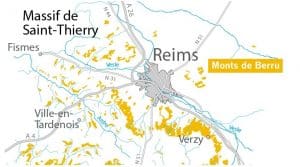

19th-century map of the Montagne de Reims. Most of the Grand Crus are visible on the right side of the map, following the tree line down to the Marne river.

Also featured are the villages of the Perle Blanche, Petite Montagne and part of the Vallée de l’Ardre which we’ll talk about below.

If you ask most wine geeks what are the regions of Champagne, you’ll probably get an answer like this:

Montagne de Reims – Known for Pinot noir

Côte des Blancs – Known for Chardonnay

Vallée de la Marne – Known for Pinot Meunier

If they know a little bit more, they’ll throw in the Côte des Sézanne (known for Chardonnay) and the Côte des Bar in the Aube (known for Pinot noir).

None of that is wrong.

But it’s very incomplete and could certainly use a few whetstones. For one, each of those regions that are known for something all have significant exceptions. There are villages or even entire sub-regions that are dominated by other grape varieties.

Map of the Montagne de Reims from the Union des Maisons de Champagne website.

Many times the exceptions are driven by changes in soils and topography. This will consequentially impact the styles of wines coming from these areas. Understanding the exceptions–and why they are exceptions–is vital to having a sharper knowledge about Champagne.

So lets cut through the haze and geek out a bit. My tools for this journey are:

Union des Maisons de Champagne website which notes that there are actually 17 regions in Champagne and gives planting details.

Tomas’s Wine Blog which is, by far, one of the most extensive and worthwhile resource on the individual villages (all 319 of them) of Champagne. Seriously, if you love Champagne, you need to bookmark this page.

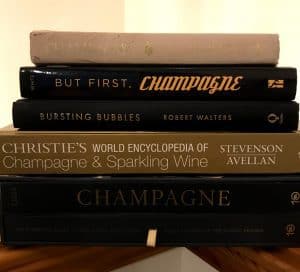

Peter Liem’s Champagne. It’s one of the Five Essential Books On Champagne precisely because it dives deep into the many subregions and exceptions of Champagne–giving you fantastic details on why they are exceptions. The box set also includes reproductions of Louis Larmat’s maps of Champagne which are a wine geek’s wet dream.

I’m not kidding about those Larmat maps. Below is a short YouTube video (2:57) made by someone from K & L wine merchants that got their hands on an old copy of the maps from Moët & Chandon. Liem’s book includes the same seven maps–minus the special Moët vineyard annotations.

Part I-Montagne de Reims

Note: Today we’re just going to cover the exceptions and unique terroir of the Montagne de Reims. Now would be a good time to have a map like this of the villages handy to follow the geekery.

The superlative about the Montagne de Reims is that the area produces powerful Pinot noir-based Champagne. It’s a reputation well earned by wines from the Grand Cru villages of Ambonnay, Bouzy, Louvois, Verzenay, Verzy, Puisieulx, Beaumont-sur-Vesle and Mailly. Here you’ll find some of the most highly regarded Pinot noir vineyards in Champagne. This includes names such as Krug’s Clos du Amobonnay, Egly-Ouriet’s Les Crayères, André Clouet’s Les Clos, Pierre Paillard’s Les Maillerettes and Mumm de Verzenay.

Champagne from the northern Grand Cru of Mailly.

But the Montagne de Reims is far from monolithic. For one thing, it’s not even really a mountain. Rather it’s a broad plateau (the Grande Montagne) with a series of hills and valleys encircling Reims.

The Grand Crus on the north and eastern segment (Mailly, Verzenay, Verzy, Beaumont-sur-Vesle, Puisieulx and Sillery) have mostly north-facing slopes which produce distinctly different Pinots than those from the south-facing slopes of Ambonnay, Bouzy and Louvois.

While the northern Pinots are still powerful, the root of their power comes more from their firm structure. Among their southern brethren, that power comes from the rich depth of fruit. This is why you see more still red Coteaux Champenois coming from these southern Grand Crus.

But it’s those unique north and north-east facing slopes that brings us to our first notable exception in Montagne de Reims. Sillery.

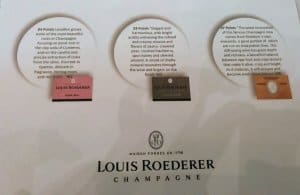

Across the broader Grande Montagne de Reims we have around 57% Pinot noir, 30% Chardonnay and 13% Pinot Meunier planted. However, in Sillery, Chardonnay leads the pack with almost 60% of plantings. The Champagne house Ruinart, which is well known for its Chardonnay-dominant Champagnes makes Sillery Chardonnay a major component of its prestige cuvée, Dom Ruinart.

In this GrapeRadio video with the cellarmaster of Ruinart, Frédéric Panaiotis, they touch on the distinctiveness of Sillery Chardonnay (3:25)–as well as that of nearby Puisieulx and Verzenay–compared to the Côte des Blancs. These Montagne de Reims Chardonnays, grown in prime Pinot noir territory, have more depth and body which puts their own unique imprint on a wine.

BTW, if you want even more hard-core geeking, check out my Geek Notes on GuildSomm’s interviews with Ruinart’s Frédéric Panaiotis about the process of Champagne and follow up.

Perle Blanche

While not officially recognized as a sub-region of the Montagne de Reims, sandwiched between the northern & southern Grand Crus is a cluster of four premier cru villages known as the Perle Blanche.

Villers-Marmery

Trépail

Billy-le-Grand

Vaudemange

Like the Côte des Blancs (as well as Côte de Beaune), the Perle Blanche vineyards face east and southeast. Here they catch the gentle morning sun before the heat of the day. While there is a deep bed of chalk throughout the Montagne de Reims, its influences are felt more keenly in the very thin topsoils of these premier crus. Trépail and Villers-Marmery particularly stand out with more than 90% of their vineyards (nearly 100% in Villers-Marmery) turned over to Chardonnay grapes that are highly prized by producers such as David Léclapart, Pehu-Simonet and Deutz.

The vlogger, My Man in Champagne, featured David Pehu in an interview (1:54) among his vines in Villers-Marmery. This will give you a good feel for the Perle Blanche.

Backwoods Meunier

Pinot Meunier is such an underrated grape variety in Champagne even though it plays an important role in many of Champagne’s most successful non-vintage blends–most notably Krug’s Grande Cuvée and Moët’s Brut Imperial (up to 40% some releases). The calling card of this grape is its ability to bud late but ripen early. This helps it escape the viticultural hazards of bud-killing springtime frost as well as diluting harvest rains.

However, climate change and warmer vintages are stirring up concerns that maybe Meunier ripens a little too early. While blocking MLF may help to retain freshness, it’s likely that the sites with north-facing slopes that have a prolonged growing season will become even more treasured for Pinot Meunier.

Vineyards in Chigny-les-Roses in the northwestern part of the Grande Montagne.

In the Grande Montagne de Reims, Meunier country starts just west of the Grand Cru village of Mailly with the notable premier cru of Ludes. The grape becomes even more important, accounting for almost 60% of plantings, in fellow 1ers Chigny-les-Roses and Trois-Puits.

While these villages don’t often show up on labels, their vineyards (and Meunier) are highly valued by large Champagne houses. Among them, notable names such as Cattier (Armand de Brignac/Ace of Spades), Canard-Duchêne, Laurent-Perrier and Taittinger.

Just a little southwest (heading towards the Vallée de la Marne) is the autre cru village of Germaine. Here Pinot Meunier makes up around 96% of all plantings and is an important source of grapes for Moët & Chandon.

These villages are so under-the-radar that’s it tough to find videos featuring their vineyards.

Instead, I’m going to show you a fun one (1:32) from Benoît Tarlant of Champagne Tarlant. This was filmed in the autre cru village of Œuilly, on the other side of the river from Montagne de Reims in the Vallée de la Marne Rive Gauche.

We’ll talk about the Vallée de la Marne in part II of this series. The north-facing slopes of the Rive Gauche in this frost-prone valley is a natural home for Pinot Meunier. What I love about this video is that you can see how tiny Meunier clusters are. It also gives great insights into what a stressful vintage 2012 was.

Massif de Saint-Thierry

The most northern vineyards in all of Champagne are located northwest of the city of Reims. This is another area of prime Pinot Meunier real estate. The grape makes up around 54% of plantings, followed by Pinot noir (29%) and Chardonnay (17%).

The autre cru of Cauroy-lès-Hermonville is almost entirely planted to just Meunier (99.3%), followed by Villers-Franqueux (83%) and Pouillon (70%).

Even the Massif de Saint-Thierry’s most well-known village, the autre cru Merfy, is paced by Pinot Meunier leading the pack with 45% of plantings–trailed by Pinot noir (35%) and Chardonnay (20%). Here the acclaimed grower-producer Chartogne-Taillet makes several highly regarded Champagnes including the vineyard-designated Les Alliées made from 100% old-vine Meunier.

All of Chartogne-Taillet’s vineyard series wines highlight the unique sand and clay soils of Merfy and Massif de Saint-Thierry. In the case of Les Alliées, the topsoil is a type of black sand that is hardly ever seen in Champagne. Levi Dalton had a fascinating interview with Alexandre Chartogne during episode 209 of his I’ll Drink to That! podcast that is well worth a listen.

Vesle et Ardre and Petite Montagne

However, the true “heart” of Meunier country in the Montagne Reims is a little further west. Here you’ll find the river valleys of the Vesle et Ardre and the hills of the Petite Montagne. Across this entire region, Meunier holds sway–representing 61% of plantings.

Like the Vallée de la Marne, early spring frost is an issue. Similarly, you tend to see the proportion of Pinot Meunier increase the more west that you go. The grape reaches its apex in the westernmost vineyards of the Vallée de l’Ardre. Also, as in the Massif de Saint-Thierry and Marne Valley, sand plays a considerable role in the terroir.

All the premier crus are clustered in the Petite Montagne, located just west of the city of Reims. These include Pargny-lès-Reims (77% Pinot Meunier), Sermiers (69% PM) and Coulommes-la-Montagne (65% PM) as well as the 100% Chardonnay dominant village of Bezannes. (Note that the UMC curiously classifies Bezannes as part of the Massif de Saint-Thierry)

Les Béguines from Jérôme Prévost’s La Closerie. Such a bloody gorgeous wine. Definitely one of the best Champagnes that I’ve ever had.

The only village of the Vesle et Ardre and Petite Montagne where Pinot noir has any sort of stronghold is the premier cru of Écueil. Planted to 76% Pinot noir, this village is an important source for the houses of Frédéric Savart and Nicolas Maillart.

A common denominator among most of these villages is the prevalence of north and north-east facing slopes.

This is true with the most notable village of the Petite Montagne, the autre cru Gueux. Pinot Meunier-dominant (84.5%), followed by Pinot noir (11.7%) and Chardonnay (3.8%), Gueux is the home of Jérôme Prévost’s La Closerie and his Les Béguines vineyard.

Prévost’s Les Béguines cuvée, almost entirely Meunier (some releases will have a tiny amount Pinot gris or Chardonnay blended in), is widely credited with reigniting interest in the grape variety. It’s certainly a wine that everyone should have on their “Must-Try” list.

Right after the Chartogne interview, Levi Dalton followed it up with an IDTT episode featuring Jérôme Prévost. Again, well worth a listen.

Monts de Berru

We’ll wrap up our overview of the exceptions to Pinot noir’s dominance in the Montagne de Reims by looking at the area’s most overlooked sub-region–the Monts de Berru. This tiny cluster of five villages, located in the hills east of Reims, are the easternmost vineyards of the Montagne de Reims. Only a few villages in the Côte des Bar and the Vitryat sub-region of the Côte des Blancs extend further east.

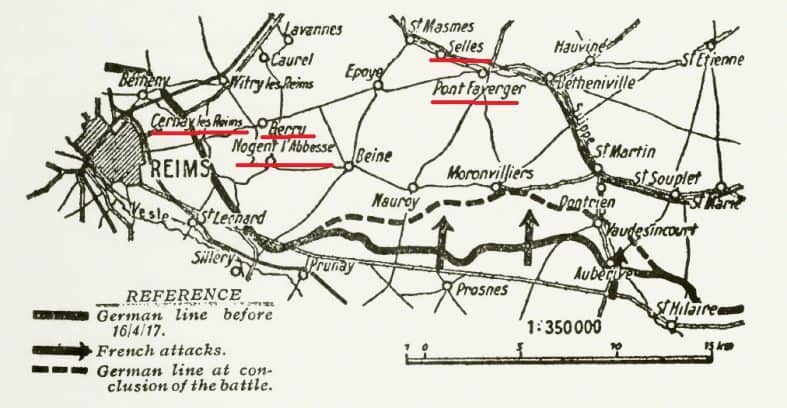

Located just east of Reims, the Monts de Berru saw a lot of fighting during WWI, particularly during the Battle of the Hills.

The 5 Champagne villages are highlighted on this map which notes French offensive gains during April & May of 1917.

Now given their northern and easterly location, you can probably guess which grape variety thrives here.

Chardonnay.

Across the 5 villages, it represents 92% of all plantings with the autre crus of Pontfaverger-Moronvilliers (100% Chardonnay going almost entirely to Moët & Chandon) and Nogent-l’Abbesse (99% of plantings) virtually exclusive to Chardonnay.

The one outlier is the north-eastern village of Selles that is planted to 94% Pinot Meunier and 6% Chardonnay. Here, too, Moët & Chandon seems to be the most significant purchaser of grapes from this autre cru.

Another Champagne house that source grapes from the Monts de Berru is Pommery as well as Pol Roger which owns vineyards in the namesake village of Berru.

Takeaways

Don’t fret. The next few parts in this series covering the exceptions of the Vallée de la Marne, Côte des Blancs and the Aube won’t be nearly as long. However, the Montagne de Reims was the best starting point to reframe folk’s thinking about the regions of Champagne.

It’s entirely too simplistic to say that the Montagne de Reims is “known for Pinot noir.” This is particularly true when there are notable Grand Cru and premier cru villages that stand out for other varieties.

The biggest reason why this “Butter Knife Knowledge” of Champagne is so pervasive is that, historically, we don’t really think that deeply about the terroir of Champagne. This is largely because the big négociant brands of Champagnes–which dominate the market–rarely talk about terroir at all.

We’re so used to thinking of Champagne as a blend of dozens, if not hundreds of villages, that it doesn’t seem like it’s worth the bother. On back labels and tech sheets, the best you ever get from most large houses is that the Chardonnay came from the Côte des Blancs, the Pinot noir from the Montagne de Reims and the Meunier from the Vallée de la Marne.

The divorcing of Champagne from terroir was a major theme of Robert Waters’ book Bursting Bubbles and it’s truly a bubble that needs to be burst.

Though only from an “autre cru”, the wines of Chartogne-Taillet exploring the terroir of Merfy shows that the Champagnes of the Massif de Saint-Thierry can stand up to any Grand Cru.

That’s a big reason why I wanted to do this series. I wanted to highlight the villages with distinctive terroir that makes them exceptions to the superlatives.

But beyond just reading about these exceptions, you need to taste. I highly encourage Champagne lovers to explore the many growers who produce single cru and single-vineyard wines. This is another area where Tomas’s wine blog is such a fantastic resource. Near the bottom of each village profile, Tomas lists many of the growers and négociants who produce wine from each place.

The Christie’s Encyclopedia of Champagne and Sparkling Wine will also list the villages of most growers in their producer profiles. Additionally, they note many individual growers that tend to be the most expressive of a cru’s terroir. These are all tremendous tools to help sharpen your understanding of Champagne.

Till next time! Tchin-Tchin!